Books

‘Secret City’ reveals long hidden stories of gay purges in federal gov’t

Gay journalist uncovers reports of closeted officials serving under 10 presidents

A new book released this week called “Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington” is drawing the attention of LGBTQ rights activists and longtime Washington insiders alike for its never-before-told stories about dozens of closeted mostly gay men and at least one lesbian who worked for 10 U.S. presidents beginning with Franklin Roosevelt through George H.W. Bush.

The book ends with the role LGBTQ people played under the 11th president it covers — Bill Clinton — by pointing out that Clinton was the first president to appoint openly gay or lesbian people to high-level administration positions.

The book’s author, gay journalist James Kirchick, says he chose to end the book with his coverage of Clinton because Clinton, for the most part, ended the restrictions against gays and lesbians serving in sensitive civilian government jobs by lifting the longstanding ban on approving government security clearances for gays.

In an interview with the Blade, Kirchick said he began his research for the book over a decade ago in his role as a Washington reporter with a longstanding interest in the Cold War and the U.S. government’s struggle to address the perceived threat of communism promoted by the then Soviet Union at the conclusion of World War II.

He said that prior to that time homosexuality was perceived as a “sin, a very bad sin,” but not a threat to the safety and security of the country. But that changed at the start of World War II when the country developed what Kirchick calls a bureaucracy for managing military and governmental secrets needed to protect the country from outside threats.

“From the Second World War until the end of the Cold War that followed, the specter of homosexuality haunted Washington,” Kirchick writes in the introduction to his book. “Nothing posed a more potent threat to a political career or exerted a more fearsome grip on the nation’s collective psyche, than the love expressed between people of the same sex,” he writes.

Kirchick notes the development widely observed by historians and LGBTQ activists that homosexuals in important government positions were perceived to be a threat to national security because societal bias and official government restrictions forced them to hide their sexual orientation and made them susceptible to blackmail by foreign government agents seeking to uncover U.S. military secrets.

In his 2006 book, “The Lavender Scare,” gay historian David K. Johnson reports how large numbers of gays were denied security clearances and forced out of their jobs because of fears of security breaches that Johnson said were never shown to have happened.

Kirchick, who said he was inspired by Johnson’s book, expands on “Lavender Scare’s” reporting by providing detailed stories of dozens of individual gay people or people incorrectly thought to be homosexual who became ensnared in investigations into their alleged sexual orientation while working for at least 10 U.S. presidents.

The presidents the book covers include Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton.

A statement announcing the release of the book says Kirchick obtained thousands of pages of declassified documents, interviewed more than 100 people, and viewed documents from presidential libraries and archives across the country to obtain the information he needed for “Secret City.”

Among those forced out of their job was Sumner Wells, a high-level State Department official and diplomatic adviser under Franklin Roosevelt. In “Secret City,” Kirchick tells how despite Wells’ reputation as an invaluable adviser to Roosevelt, the president made it clear Wells could not remain in the administration after word got out that he had solicited one or more young men for sex who worked as porters on passenger trains that Wells had taken to travel to different parts of the country.

Not all of the book’s stories involve government officials. In one story Kirchick tells about Oliver Sipple, a former U.S. Marine who saved the life of President Gerald Ford by deflecting the gun of a woman who attempted to shoot Ford as he emerged from an event in San Francisco. The widely publicized incident prompted some gay activists to publicly disclose that Sipple was gay and should be hailed as a hero.

The book reports that Sipple was not out publicly and became emotionally distraught after being outed. His parents reacted in a hostile way after learning from press reports that their son was a homosexual and told him he was no longer welcome to visit his parents, according to the book.

A far more positive story emerged during the administration of President Jimmy Carter. The book reports on a development reported by the Washington Blade and other media outlets at the time it became known in 1979 when Jamie Shoemaker, a gay man who worked as a linguist with the U.S. National Security Agency, or NSA, had his security clearance revoked and was told he would be fired after officials at the highly secretive agency discovered he was gay.

Shoemaker contested the effort to dismiss him and retained D.C. gay rights pioneer Frank Kameny, who was a recognized expert in helping gays contest efforts to revoke government security clearances, to represent him. In a development that surprised many political observers, former Admiral Bobby Ray Inman, who Carter had appointed as director of the NSA, determined that Shoemaker was not a threat to the agency’s secrets and could retain his security clearance and his job.

Inman made that determination after Kameny and Shoemaker made it clear that Shoemaker was an out gay man who had no problem disclosing his sexual orientation at work if doing so did not jeopardize his job. Shoemaker became the first known gay person to be allowed to retain a high-level security clearance at a U.S. government intelligence agency such as the NSA and possibly at any government agency or department.

Shoemaker, who has since retired, told the Blade that in recent years, an LGBTQ employee group at the NSA has invited him to return to the agency’s headquarters as a guest speaker for the group’s LGBTQ Pride event with the full approval of NSA officials. The welcoming of Shoemaker at the NSA in recent years is viewed by activists as a development illustrating the dramatic changes that have taken place in support of LGBTQ workers at security agencies like the NSA, the CIA, and the FBI.

But Kirchick includes in his book a slightly less positive story about one of Carter’s White House aides, Midge Costanza, who Kirchick says was known by political insiders to be a lesbian who never publicly acknowledged her sexual orientation. Costanza became widely known and praised by LGBTQ activists when she invited LGBTQ leaders from across the country to the White Houses to provide her and the Carter administration with a briefing on LGBTQ issues. The meeting became the first known time that gay and lesbian rights advocates had been invited to the White House for an official meeting.

Carter himself was out of town at the time of the meeting for a pre scheduled visit to the presidential retreat at Camp David, White House officials said at the time.

Kirchick reports that in the following year or two, during Carter’s first and only term in office as president, higher up White House officials who Kirchick says were known as the “Georgia Mafia” because of their association with Carter at the time he was Georgia governor, disparaged Costanza over claims that she was pushing positions too far to the left. Among other things, the White House officials moved Costanza’s office from a prestigious location near the Oval Office to an out of the way basement space. Costanza a short time later resigned and returned to Rochester, New York, where she began her political career.

Despite what Kirchick said was a setback of sorts for the LGBTQ cause by the outcome of Costanza’s tenure at the White House, he writes in his book that the situation soon improved for gay people working in the federal government in Washington.

“The story of the secret city is also the story of a nation overcoming one of its deepest fears,” Kirchick writes in the concluding chapter of “Secret City.”

“Only when gay people started living their lives openly did the hysteria start to become plain for what its was,” he writes. “Across the broad sweep of American history, no minority group has witnessed a more rapid transformation in its status, in the eyes of their fellow citizens, than gay people in the second half of the twentieth century,” Kirchick concludes.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

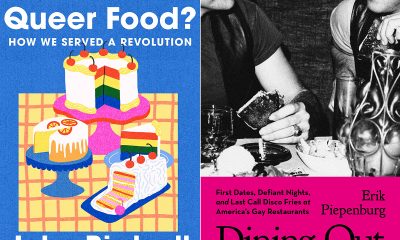

Two new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

Visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers

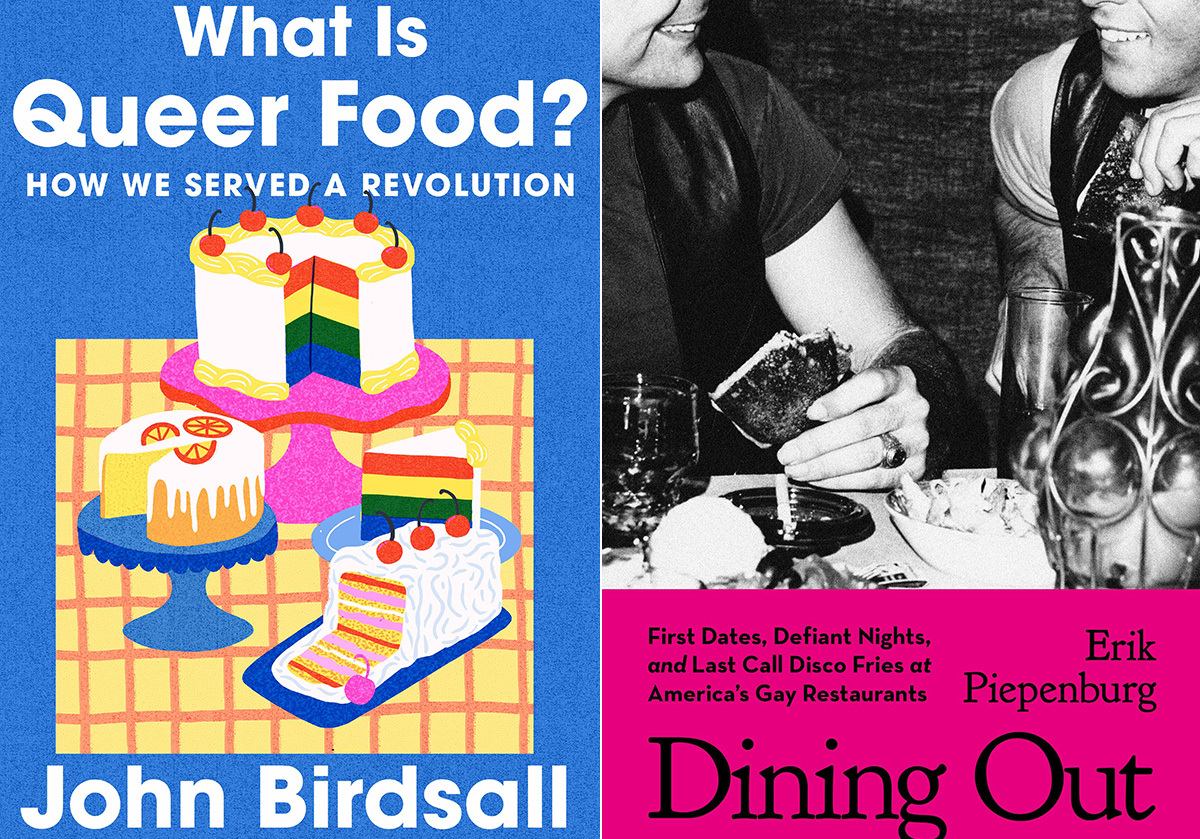

‘What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution’

By John Birdsall

c.2025, W.W. Norton

$29.99/304 pages

‘Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants’

By Erik Piepenburg

c.2025, Grand Central

$30/352 pages

You thought a long time about who sits where.

Compatibility is key for a good dinner party, so place cards were the first consideration; you have at least one left-hander on your guest list, and you figured his comfort into your seating chart. You want the conversation to flow, which is music to your ears. And you did a good job but, as you’ll see with these two great books on dining LGBTQ-style, it’s sometimes not who sits where, but whose recipes were used.

When you first pick up “What is Queer Food?” by John Birdsall, you might miss the subtitle: “How We Served a Revolution.” It’s that second part that’s important.

Starting with a basic gay and lesbian history of America, Birdsall shows how influential and (in)famous 20th century queer folk set aside the cruelty and discrimination they received, in order to live their lives. They couldn’t speak about those things, he says, but they “sat down together” and they ate.

That suggested “a queer common purpose,” says Birdsall. “This is how who we are, dahling, This is how we feed our own. This is how we stay alive.”

Readers who love to cook, bake or entertain, collect cookbooks, or use a fork will want this book. Its stories are nicely served, they’re addicting, and they may send you in search of cookbooks you didn’t know existed.

Sometimes, though, you don’t want to be stuck in the kitchen, you want someone else to bring the grub. “Dining Out” by Erik Piepenburg is an often-nostalgic, lively look at LGBTQ-friendly places to grab a meal – both now and in the past.

In his introduction, Piepenburg admits that he’s a journalist, “not a historian or an academic,” which colors this book, but not negatively. Indeed, his journeys to “gay restaurants” – even his generous and wide-ranging definitions of the term – happily influence how he presents his narrative about eateries and other establishments that have fed protesters, nourished budding romances, and offered audacious inclusion.

Here, there are modern tales of drag lunches and lesbian-friendly automats that offered “cheap food” nearly a century ago. You’ll visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers on holidays. Stepping back, you’ll read about AIDS activism at gay-friendly establishments, and mostly gay neighborhood watering holes. Go underground at a basement bar; keep tripping and meet proprietors, managers, customers and performers. Then take a peek into the future, as Piepenburg sees it.

The locales profiled in “Dining Out” may surprise you because of where they can be found; some of the hot-spots practically beg for a road trip.

After reading this book, you’ll feel welcome at any of them.

If these books don’t shed enough light on queer food, then head to your favorite bookstore or library and ask for help finding more. The booksellers and librarians there will put cookbooks and history books directly in your hands, and they’ll help you find more on the history and culture of the food you eat. Grab them and you’ll agree, they’re pretty tasty reads.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

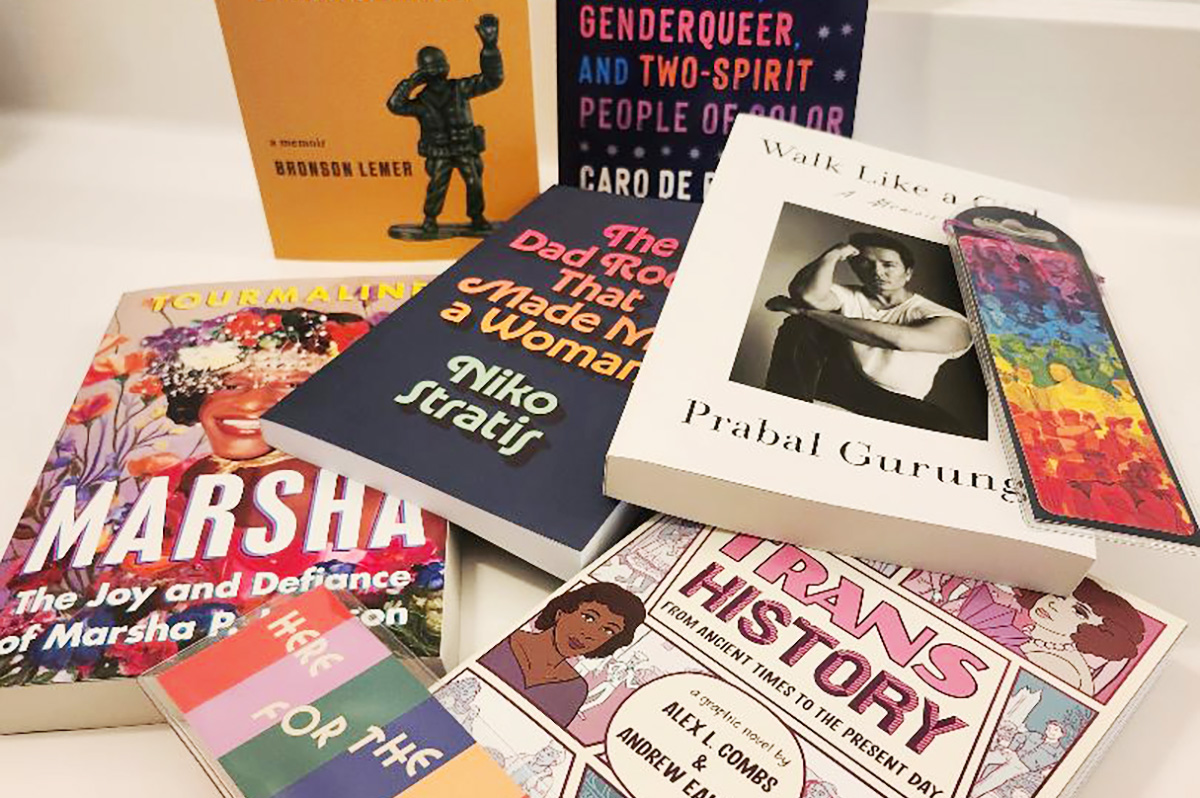

You’re going to be on your feet a lot this month.

Marching in parades, dancing in the streets, standing up for people in your community. But you’re also likely to have some time to rest and reflect – and with these great new books, to read.

First, dip into a biography with “Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson” by Tourmaline (Tiny Rep Books, $30), a nice look at an icon who, rumor has it, threw the brick that started a revolution. It’s a lively tale about Marsha P. Johnson, her life, her activism before Stonewall and afterward. Reading this interesting and highly researched history is a great way to spend some time during Pride month.

For the reader who can’t live without music, try “The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman” by Niko Stratis (University of Texas Press, $27.95), the story of being trans, searching for your place in the world, and finding it in a certain comfortable genre of music. Also look for “The Lonely Veteran’s Guide to Companionship” by Bronson Lemer (University of Wisconsin Press, $19.95), a collection of essays that make up a memoir of this and that, of being queer, basic training, teaching overseas, influential books, and life.

If you still have room for one more memoir, try “Walk Like a Girl” by Prabal Gurung (Viking, $32.00). It’s the story of one queer boy’s childhood in India and Nepal, and the intolerance he experienced as a child, which caused him to dream of New York and the life he imagined there. As you can imagine, dreams and reality collided but nonetheless, Gurung stayed, persevered, and eventually became an award-winning fashion designer, highly sought by fashion icons and lovers of haute couture. This is an inspiring tale that you shouldn’t miss.

No Pride celebration is complete without a history book or two.

In “Trans History: From Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Alex L. Combs & Andrew Eakett ($24.99, Candlewick Press), you’ll see that being trans is something that’s as old as humanity. One nice part about this book: it’s in graphic novel form, so it’s lighter to read but still informative. Lastly, try “So Many Stars: An Oral History of Trans, Nonbinary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit People of Color” by Caro De Robertis (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $32.00) a collection of thoughts, observations, and truths from over a dozen people who share their stories. As an “oral history,” you’ll be glad to know that each page is full of mini-segments you can dip into anywhere, read from cover to cover, double-back and read again. It’s that kind of book.

And if these six books aren’t enough, if they don’t quite fit what you crave now, be sure to ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for help. There are literally tens of thousands of books that are perfect for Pride month and beyond. They’ll be able to determine what you’re looking for, and they’ll put it directly in your hands. So stand up. March. And then sit and read.

You’ve done your share of marching.

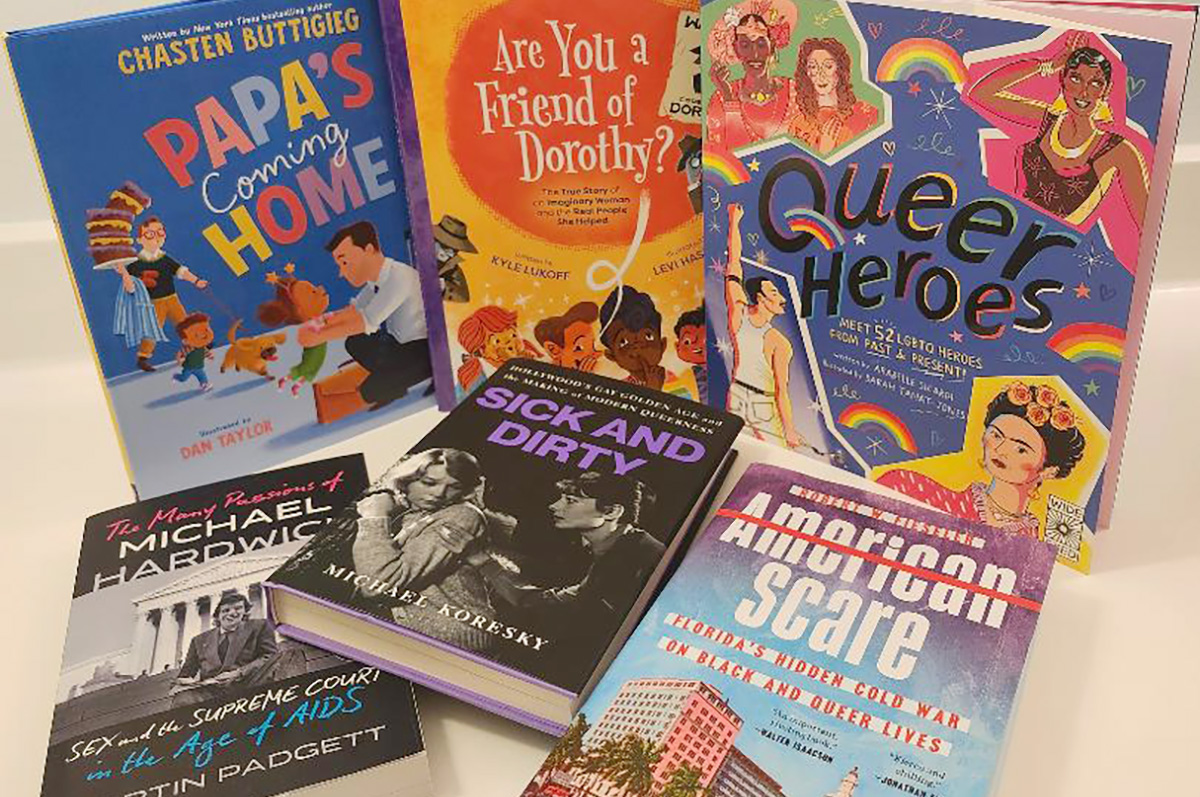

You’re determined to wring every rainbow-hued thing out of this month. The last of the parties hasn’t arrived yet, neither have the biggest celebrations and you’re primed but – OK, you need a minute. So pull up a chair, take a deep breath, and read these great books on gay history, movies, and more.

You probably don’t need to be told that harassment and discrimination was a daily occurrence for gay people in the past (as now!), but “American Scare: Florida’s Hidden Cold War on Black and Queer Lives” by Robert W. Fieseler (Dutton, $34) tells a story that runs deeper than you may know. Here, you’ll read a historical expose with documented, newly released evidence of a systemic effort to ruin the lives of two groups of people that were perceived as a threat to a legislature full of white men.

Prepared to be shocked, that’s all you need to know.

You’ll also want to read the story inside “The Many Passions of Michael Hardwick: Sex and the Supreme Court in the Age of AIDS” by Martin Padgett (W.W. Norton & Company, $31.99), which sounds like a novel, but it’s not. It’s the story of one man’s fight for a basic right as the AIDS crisis swirls in and out of American gay life and law. Hint: this book isn’t just old history, and it’s not just for gay men.

Maybe you’re ready for some fun and who doesn’t like a movie? You know you do, so you’ll want “Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness” by Michael Koresky (Bloomsbury, $29.99). It’s a great look at the Hays Code and what it allowed audiences to see, but it’s also about the classics that sneaked beneath the code. There are actors, of course, in here, but also directors, writers, and other Hollywood characters you may recognize. Grab the popcorn and settle in.

If you have kids in your life, they’ll want to know more about Pride and you’ll want to look for “Pride: Celebrations & Festivals” by Eric Huang, illustrated by Amy Phelps (Quarto, $14.99), a story of inclusion that ends in a nice fat section of history and explanation, great for kids ages seven-to-fourteen. Also find “Are You a Friend of Dorothy? The True Story of an Imaginary Woman and the Real People She Helped Shape” by Kyle Lukoff, illustrated by Levi Hastings (Simon & Schuster, $19.99), a lively book about a not-often-told secret for kids ages six-to-ten; and “Papa’s Coming Home” by Chasten Buttigieg, illustrated by Dan Taylor (Philomel, $19.99), a sweet family tale for kids ages three-to-five.

Finally, here’s a tween book that you can enjoy, too: “Queer Heroes” by Arabelle Sicardi, illustrated by Sarah Tanat-Jones (Wide Eyed, $14.99), a series of quick-to-read biographies of people you should know about.

Want more Pride books? Then ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for more, because there are so many more things to read. Really, the possibilities are almost endless, so march on in.

Books

A boy-meets-boy, family-mess story with heat

New book offers a stunning, satisfying love story

‘When the Harvest Comes’

By Denne Michele Norris

c.2025, Random House

$28/304 pages

Happy is the bride the sun shines on.

Of all the clichés that exist about weddings, that’s the one that seems to make you smile the most. Just invoking good weather and bright sunshine feels like a cosmic blessing on the newlyweds and their future. It’s a happy omen for bride and groom or, as in the new book “When the Harvest Comes” by Denne Michele Norris, for groom and groom.

Davis Freeman never thought he could love or be loved like this.

He was wildly, wholeheartedly, mind-and-soul smitten with Everett Caldwell, and life was everything that Davis ever wanted. He was a successful symphony musician in New York. They had an apartment they enjoyed and friends they cherished. Now it was their wedding day, a day Davis had planned with the man he adored, the details almost down to the stitches in their attire. He’d even purchased a gorgeous wedding gown that he’d never risk wearing.

He knew that Everett’s family loved him a lot, but Davis didn’t dare tickle the fates with a white dress on their big day. Everett’s dad, just like Davis’s own father, had considerable reservations about his son marrying another man – although Everett’s father seemed to have come to terms with his son’s bisexuality. Davis’s father, whom Davis called the Reverend, never would. Years ago, father and son had a falling-out that destroyed any chance of peace between Davis and his dad; in fact, the door slammed shut to any reconciliation.

But Davis tried not to think about that. Not on his wedding day. Not, unbeknownst to him, as the Reverend was rushing toward the wedding venue, uninvited but not unrepentant. Not when there was an accident and the Reverend was killed, miles away and during the nuptials.

Davis didn’t know that, of course, as he was marrying the love of his life. Neither did Everett, who had familial problems of his own, including homophobic family members who tried (but failed) to pretend otherwise.

Happy is the groom the sun shines on. But when the storm comes, it can be impossible to remain sunny.

What can be said about “When the Harvest Comes?” It’s a romance with a bit of ghost-pepper-like heat that’s not there for the mere sake of titillation. It’s filled with drama, intrigue, hate, characters you want to just slap, and some in bad need of a hug.

In short, this book is quite stunning.

Author Denne Michele Norris offers a love story that’s everything you want in this genre, including partners you genuinely want to get to know, in situations that are real. This is done by putting readers inside the characters’ minds, letting Davis and Everett themselves explain why they acted as they did, mistakes and all. Don’t be surprised if you have to read the last few pages twice to best enjoy how things end. You won’t be sorry.

If you want a complicated, boy-meets-boy, family-mess kind of book with occasional heat, “When the Harvest Comes” is your book. Truly, this novel shines.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Chronicling disastrous effects of ‘conversion therapy’

New book uncovers horror, unexpected humor of discredited practice

‘Shame-Sex Attraction: Survivors’ Stories of Conversion Therapy’

By Lucas F. W. Wilson

c.2025, Jessica Kingsley Publishers

$21.95/190 pages

You’re a few months in, and it hasn’t gotten any easier.

You made your New Year’s resolutions with forethought, purpose, and determination but after all this time, you still struggle, ugh. You’ve backslid. You’ve cheated because change is hard. It’s sometimes impossible. And in the new book, “Shame-Sex Attraction” by Lucas F. W. Wilson, it can be exceptionally traumatic.

Progress does not come without problems.

While it’s true that the LGBTQ community has been adversely affected by the current administration, there are still things to be happy about when it comes to civil rights and acceptance. Still, says Wilson, one “particularly slow-moving aspect… has been the fight against what is widely known as conversion therapy.”

Such practices, he says, “have numerous damaging, death-dealing, and no doubt disastrous consequences.” The stories he’s collected in this volume reflect that, but they also mirror confidence and strength in the face of detrimental treatment.

Writer Gregory Elsasser-Chavez was told to breathe in something repellent every time he thought about other men. He says, in the end, he decided not to “pray away the gay.” Instead, he quips, he’d “sniff it away.”

D. Apple became her “own conversation therapist” by exhausting herself with service to others as therapy. Peter Nunn’s father took him on a surprise trip, but the surprise was a conversion facility; Nunn’s father said if it didn’t work, he’d “get rid of” his 15-year-old son. Chaim Levin was forced to humiliate himself as part of his therapy.

Lexie Bean struggled to make a therapist understand that they didn’t want to be a man because they were “both.” Jordan Sullivan writes of the years it takes “to re-integrate and become whole” after conversion therapy. Chris Csabs writes that he “tried everything to find the root of my problem” but “nothing so far had worked.”

Says Syre Klenke of a group conversion session, “My heart shattered over and over as people tried to console and encourage each other…. I wonder if each of them is okay and still with us today.”

Here’s a bit of advice for reading “Shame-Sex Attraction”: dip into the first chapter, maybe the second, then go back and read the foreword and introduction, and resume.

The reason: author Lucas F. W. Wilson’s intro is deep and steep, full of footnotes and statistics, and if you’re not prepared or you didn’t come for the education, it might scare you away. No, the subtitle of this book is likely why you’d pick the book up so because that’s what you really wanted, indulge before backtracking.

You won’t be sorry; the first stories are bracing and they’ll steel you for the rest, for the emotion and the tears, the horror and the unexpected humor.

Be aware that there are triggers all over this book, especially if you’ve been subjected to anything like conversion therapy yourself. Remember, though, that the survivors are just that: survivors, and their strength is what makes this book worthwhile. Even so, though “Shame-Sex Attraction” is an essential read, that doesn’t make it any easier.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

‘Pronoun Trouble’ reminds us that punctuation matters

‘They’ has been a shape-shifter for more than 700 years

‘Pronoun Trouble’

By John McWhorter

c.2025, Avery

$28/240 pages

Punctuation matters.

It’s tempting to skip a period at the end of a sentence Tempting to overuse exclamation points!!! very tempting to MeSs with capital letters. Dont use apostrophes. Ask a question and ignore the proper punctuation commas or question marks because seriously who cares. So guess what? Someone does, punctuation really matters, and as you’ll see in “Pronoun Trouble” by John McWhorter, so do other parts of our language.

Conversation is an odd thing. It’s spontaneous, it ebbs and flows, and it’s often inferred. Take, for instance, if you talk about him. Chances are, everyone in the conversation knows who him is. Or he. That guy there.

That’s the handy part about pronouns. Says McWhorter, pronouns “function as shorthand” for whomever we’re discussing or referring to. They’re “part of our hardwiring,” they’re found in all languages, and they’ve been around for centuries.

And, yes, pronouns are fluid.

For example, there’s the first-person pronoun, I as in me and there we go again. The singular I solely affects what comes afterward. You say “he-she IS,” and “they-you ARE” but I am. From “Black English,” I has also morphed into the perfectly acceptable Ima, shorthand for “I am going to.” Mind blown.

If you love Shakespeare, you may’ve noticed that he uses both thou and you in his plays. The former was once left to commoners and lower classes, while the latter was for people of high status or less formal situations. From you, we get y’all, yeet, ya, you-uns, and yinz. We also get “you guys,” which may have nothing to do with guys.

We and us are warmer in tone because of the inclusion implied. She is often casually used to imply cars, boats, and – warmly or not – gay men, in certain settings. It “lacks personhood,” and to use it in reference to a human is “barbarity.”

And yes, though it can sometimes be confusing to modern speakers, the singular word “they” has been a “shape-shifter” for more than 700 years.

Your high school English teacher would be proud of you, if you pick up “Pronoun Trouble.” Sadly, though, you might need her again to make sense of big parts of this book: What you’ll find here is a delightful romp through language, but it’s also very erudite.

Author John McWhorter invites readers along to conjugate verbs, and doing so will take you back to ancient literature, on a fascinating journey that’s perfect for word nerds and anyone who loves language. You’ll likely find a bit of controversy here or there on various entries, but you’ll also find humor and pop culture, an explanation for why zie never took off, and assurance that the whole flap over strictly-gendered pronouns is nothing but overblown protestation. Readers who have opinions will like that.

Still, if you just want the pronoun you want, a little between-the-lines looking is necessary here, so beware. “Pronoun Trouble” is perfect for linguists, writers, and those who love to play with words but for most readers, it’s a different kind of book, period.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

New book helps vulnerable people to stay safe

‘The Cost of Fear’

By Meg Stone

c.2025, Beacon Press

$26.95/232 pages

The footsteps fell behind you, keeping pace.

They were loud as an airplane, a few decibels below the beat of your heart. Yes, someone was following you, and you shouldn’t have let it happen. You’re no dummy. You’re no wimp. Read the new book, “The Cost of Fear” by Meg Stone, and you’re no statistic. Ask around.

Query young women, older women, grandmothers, and teenagers. Ask gay men, lesbians, and trans individuals, and chances are that every one of them has a story of being scared of another person in a public place. Scared – or worse.

Says author Meg Stone, nearly half of the women in a recent survey reported having “experienced… unwanted sexual contact” of some sort. Almost a quarter of the men surveyed said the same. Nearly 30 percent of men in another survey admitted to having “perpetrated some form of sexual assault.”

We focus on these statistics, says Stone, but we advise ineffectual safety measures.

“Victim blame is rampant,” she says, and women and LGBTQ individuals are taught avoidance methods that may not work. If someone’s in the “early stages of their careers,” perpetrators may still hold all the cards through threats and career blackmail. Stone cites cases in which someone who was assaulted reported the crime, but police dropped the ball. Old tropes still exist and repeating or relying on them may be downright dangerous.

As a result of such ineffectiveness, fear keeps frightened individuals from normal activities, leaving the house, shopping, going out with friends for an evening.

So how can you stay safe?

Says Stone, learn how to fight back by using your whole body, not just your hands. Be willing to record what’s happening. Don’t abandon your activism, she says; in fact, join a group that helps give people tools to protect themselves. Learn the right way to stand up for someone who’s uncomfortable or endangered. Remember that you can’t be blamed for another person’s bad behavior, and it shouldn’t mean you can’t react.

If you pick up “The Cost of Fear,” hoping to learn ways to protect yourself, there are two things to keep in mind.

First, though most of this book is written for women, it doesn’t take much of a leap to see how its advice could translate to any other world. Author Stone, in fact, includes people of all ages, genders, and all races in her case studies and lessons, and she clearly explains a bit of what she teaches in her classes. That width is helpful, and welcome.

Secondly, she asks readers to do something potentially controversial: she requests changes in sentencing laws for certain former and rehabilitated abusers, particularly for offenders who were teens when sentenced. Stone lays out her reasoning and begs for understanding; still, some readers may be resistant and some may be triggered.

Keep that in mind, and “The Cost of Fear” is a great book for a young adult or anyone who needs to increase alertness, adopt careful practices, and stay safe. Take steps to have it soon.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

A taste for the macabre with a side order of sympathy

New book ‘The Lamb’ is for fans of horror stories

‘The Lamb: A Novel’

By Lucy Rose

c.2025, Harper

$27.99/329 pages

What’s for lunch?

You probably know at breakfast what you’re having a few hours later. Maybe breast of chicken in tomato sauce. Barbecued ribs, perhaps? Leg of lamb, beef tongue, pickled pigs’ feet, liver and onions, the possibilities are just menus away. Or maybe, as in the new book, “The Lamb” by Lucy Rose, you’ll settle for a rump roast and a few lady fingers.

Margot was just four years old when she noticed the mold on the shower walls, and wondered what it might taste like. She also found fingers in the shower drain from the last “stray,” the nails painted purple, and she wondered why they hadn’t been nibbled, too.

Cooked right, fingers and rumps were the best parts.

Later, once Margot started school, Mama depended on her to bring strays from the woods to their cottage, and Mama would give them wine and warm them up. She didn’t often leave the house unless it was to bury clothing and bones, but she sometimes welcomed a gardener who was allowed to leave. There was a difference, you see, between strays and others.

But Eden? Margot couldn’t quite figure her out.

She actually liked Eden, who seemed like a stray but obviously wasn’t. Eden was pretty; she never yelled at Margot, although she did take Margot’s sleeping spot near Mama. Eden made Mama happy; Margot could hear them in the bedroom sometimes, making noises like Mama did when the gardener visited. Eden was a very good cook. She made Mama softer, and she made promises for better times.

And yet, things never got better. Margot was not supposed to call attention to herself, but she wanted friends and a real life. If she was honest, she didn’t want to eat strays anymore, either, she was tired of the pressure to bring home dinner, and things began to unravel. Maybe Mama didn’t love Margot anymore. Maybe she loved Eden better or maybe Mama just ached from hunger.

Because you know what they say: two’s company, three’s a meal.

Not a book to read at lunch? No, probably not – although once you become immersed in “The Lamb,” it’ll be easy to swallow and hard to put down.

For sure, author Lucy Rose presents a somewhat coming-of-age chiller with a gender-twisty plot line here, and while it’s occasionally a bit slow and definitely cringey, it’s also really quite compelling. Rose actually makes readers feel good about a character who indulges in something so entirely, repulsively taboo, which is a very surprising – but oddly satisfying – aspect of this unique tale. Readers, in fact, will be drawn to the character Margo’s innocence-turned-eyes-wide-open and it could make you grow a little protective of her as she matures over the pages. That feeling plays well inside the story and it makes the will-they-won’t-they ending positively shivery.

Bottom line, if you have a taste for the macabre with a side order of sympathy, then “The Lamb” is your book and don’t miss it. Fans of horror stories, this is a novel you’ll eat right up.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

‘Cleavage’ explores late-in-life transition

An enjoyable collection of work from a born storyteller

‘Cleavage: Men, Women, and the Space Between Us’

By Jennifer Finney Boylan

c.2025, Celadon Books

$29/256 pages

When it came to friends and family, your cup used to runneth over.

You had plenty of both and then, well, life and politics wedged an ocean-sized chasm between you and it makes you sad. And yet – are you really all that far apart? As in the new memoir, “Cleavage” by Jennifer Finney Boylan, maybe you’re still two peas in a pod.

Once upon a time not so long ago, Jennifer Finney Boylan was one of “a group of twelve-year-old Visigoths” intent on mischief. They hung around, did normal boy stuff, setting off rockets, roughhousing, roaming, rambling, and bike-riding. The difference between Boylan and the other boys in her group was that Jim Boylan knew she was really a girl.

Then, she vowed that it was a “secret no soul would ever know,” and James went to college, enjoyed a higher metabolism, dated, fell in love too easily, then married a woman and fathered two boys but there was still that tug. Boylan carried the child she once was in her heart – “How I loved the boy I’d been!” – but she was a woman “on the inside” and saying it aloud eventually became critical.

Boylan had a hard talk with her wife, Deedie, knowing that it could be the end of their marriage. She’s eternally grateful now that it wasn’t.

She’s also grateful that she became a woman when she did, when politics had little to do with that personal decision. She worries about her children, one who is trans, both of whom are good, successful people who make Boylan proud. She tries to help other trans women. And she thinks about the words her mother often said: “Love will prevail.”

“Our lives are not a thing to be ashamed of,” Boylan says, “or apologized for, or explained. Our lives are a thing of wildness, and tenderness, and joy.”

Judge “Cleavage” by its cover, and you might think you’ll get a primer on anatomy. Nope, author Jennifer Finney Boylan only has one chapter on the subject, among many. Instead, she leans heavily on her childhood and her transition rather late in life, her family, and her friends to continue where her other books left off, to update, correct, and to share her thoughts on that invisible division. In sum, she guesses that “a huge chunk of the population… still doesn’t understand this trans business at all.”

Let that gentle playfulness be a harbinger of what you’ll read: some humor about her journey, and many things that might make your heart hurt; self-inspection that seems confidential and a few oh-so-deliciously well-placed snarks; and memories that, well told and satisfying, are both nostalgic and personal from “both the Before and the After.”

This book has the feel of having a cold one with a friend and Boylan fans will devour it. It’s also great for anyone who is trans-curious or just wants to read an enjoyable collection of work from a born storyteller. No matter what you want from it, what you’ll find in “Cleavage” is a treasure chest.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

From genteel British wealth to trans biker

Memoir ‘Frighten the Horses’ a long but essential read

‘Frighten the Horses: A Memoir’

By Oliver Radclyffe

c.2024, Roxane Books/Grove Atlantic

$28/352 pages

Finding your own way.

It’s a rite of passage for every young person, a necessity on the path to adulthood. You might have had help with it. You might have listened to your heart alone on the quest to find your own way. And sometimes, as in the new memoir, “Frighten the Horses” by Oliver Radclyffe, you may have to find yourself first.

If you had observed Oliver Radclyffe in a random diner a few years ago, you’d have seen a blonde, bubbly, but harried mother with four active children under age seven and a distracted husband. You probably wouldn’t have seen trouble, but it was there.

“Nicky,” as Radclyffe was known then, was simmering with something that was just coming to the forefront.

As a young child, Nicky’d been raised in comfort in a family steeped in genteel British wealth, attended a private all-girl’s school, and never wanted for anything. She left all that behind as a young adult, and embraced the biker lifestyle and everything it entailed. The problem now wasn’t that she missed her old ways; it was that she hated life as a wife and mother. Her dreams were filled with fantasies of “exactly who I was: a man on a motorbike, in love with a woman.”

But being a man? No, that wasn’t quite right.

It took every bit of courage she had to say she was gay, that she thought constantly about women, that she hated sex with men. When she told her husband, he was hurt but mostly unbothered, insisting that she tell absolutely no one. They could remain married and just go forward. Nothing had to change.

But everything had already changed for Nicky.

Once she decided finally to come out, she learned that friends had already suspected. Family was supportive. It would be OK. But as Nicky began to experiment with a newfound freedom to be with women, one thing became clear: having sex with a woman was better when she imagined doing it as a man.

In his opening chapter, author Oliver Radclyffe shares an anecdote about the confusion the father of Radclyffe’s son’s friend had when picking up the friend. Readers may feel the same sentiment.

Fortunately, “Frighten the Horses” gets better — and it gets worse. Radclyffe’s story is riveting, told with a voice that’s distinct, sometimes poker-faced, but compelling; you’ll find yourself agreeing with every bit of his outrage and befuddlement with coming out in a way that feels right. When everything falls into place, it’s a relief for both author and reader.

And yet, it’s hard to get to this point because this memoir is just too long. It lags where you’ll wish it didn’t. It feels like being burrito-wrapped in a heavy-weighted blanket: You don’t necessarily want out, but you might get tired of being in it.

Still, it remains that this peek at transitioning, however painful, is essential reading for anyone who needs to understand how someone figures things out. If that’s you, then consider “Frighten the Horses” and find it.

-

Breaking News3 days ago

Breaking News3 days agoMajor victory for LGBTQ funding in LA County

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoKoaty & Sumner: Finding love in the adult industry

-

Books5 days ago

Books5 days agoTwo new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

-

Miscellaneous2 days ago

Miscellaneous2 days agoCan you really find true love in LA? Insights from a queer matchmaker

-

Commentary10 hours ago

Commentary10 hours agoBreaking the mental health mold with Ketamine: insights from creator of Better U

-

El Salvador3 days ago

El Salvador3 days agoLa marcha LGBTQ+ desafía el silencio en El Salvador

-

Arts & Entertainment2 days ago

Arts & Entertainment2 days agoIntuitive Shana gives us her hot take for July’s tarot reading