Notables

Norm Kent, co-founder of South Florida Gay News, dies at 73

Marijuana and LGBTQ rights champion, baseball fanatic, radio talk host passed away at home

By Steve Rothaus for South Florida Gay News | FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. — Attorney Norm Kent — relentless fighter for marijuana and LGBT rights, baseball fanatic, popular radio talk host and co-founder of South Florida Gay News — died at 73 on April 13, 18 months after learning he had pancreatic cancer.

In his final interview on March 28, Kent told SFGN he was diagnosed in October 2021. “That day, I said, ‘Let’s fly to Atlanta and go to a Dodgers game. If they’re telling me I have cancer, we’re going to a baseball game.’”

“You definitely can’t accuse him of not being interesting,” said Fort Lauderdale attorney Russell Cormican, Kent’s law partner for nearly 25 years.

“The most important thing looking at Norm’s legacy is that he reminds us how important it is to stand up for what you believe in, no matter how unpopular it might be or what types of repercussions or blowback you might get from people, if you know what you’re doing is the right thing,” said Cormican, 51. “When he sees an injustice, he’s not afraid to lead the call against it. That’s the common thread that’s gone through his life.”

Born Norman Elliott Kent in Brooklyn, N.Y., on Oct. 18, 1949, his family soon moved to North Woodmere in Nassau County on Long Island.

“Ever since I was a little kid growing up in North Woodmere and taking Bus 53 to junior varsity games, I was a good, competitive baseball player. The doctor once said I had steel springs in my legs,” Kent said. “I just loved the game. I love it now because you don’t know what’s going to happen on the next pitch. It’s not scripted like a movie. Like comedians, you never know what the next joke is going to be.”

To never miss a game, Kent equipped his longtime small, two-bedroom Victoria Park home with 16 televisions.

“It looks like mission control,” Cormican said. “Heaven forbid there are four baseball games on. He has to see each one.”

Thirty years ago, he even owned a baseball card shop at the Gateway Shopping Center in Fort Lauderdale, Norm Kent’s Baseball Heaven.

Kent, who is survived by older brother Richard and younger brother Alan, once flirted with becoming a professional ballplayer but their dad Jesse told him, “You’re going to be the lawyer in the family.”

After graduating in 1971 from Hofstra University on Long Island with a bachelor’s degree in social sciences and sociology, Kent made his father happy and received a Hofstra law degree in 1975.

During college, Kent began establishing a national reputation as a leading proponent of legalizing marijuana use.

Kent joined NORML, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws in 1971. He served 1992-94 on NORML’s national board, rejoined the governing body in 1998 and from 2013-14 served as national board chairman.

In 1988, Kent made headlines representing singer Elvy Musikka, a Hollywood woman nearly blinded by cataracts who was busted for growing pot in her own backyard.

“After 23 different operations for cataracts,” Kent recalled March 28, “she found the only thing that let her see was by taking marijuana. It had a certain THC in it which let her see.”

He continued: “Who was her government, or the president, to stop her from seeing? And when the police came to her house in Hollywood and said we’re going to have to arrest you for smoking pot, she said, ‘I dare you to. I don’t care. It’s my life. It’s my right to see.’

“She went to a lawyer. She went to me. And I said let’s go to court. We argued a case in [Broward Circuit Court] before Judge Mark E. Polen and we won. He said your right to smoke marijuana is a lot more important than the right of the government to tell you what to do with what you can smoke. That case became the seminal case for hundreds of others.”

While dying of cancer, Kent himself couldn’t find pain relief smoking marijuana: “No,” he said, “I had a respiratory condition in 2018 when I got a defibrillator and pacemaker.”

Shortly after college, Kent worked briefly as an urban affairs analyst for the New York Legislature, and in 1978 relocated to South Florida where his parents had moved.

Kent never officially told them he was gay.

“My parents always suspected he was gay from the time he moved to Fort Lauderdale,” said his brother Alan, a retired psychologist. “They would always ask me, ‘Do you think Norman is gay?’”

Alan Kent, who also is gay, came out to their parents in 1982. Five years later, after their father died, Norm called Alan from Provincetown, Mass., with some news: I’m gay.

“I said really? Tell me something I don’t know,” Alan Kent recalled.

Before he died, Norm Kent said that for him “there was no such thing as being in [the closet].”

“There was always this fear that as a gay lawyer it might cost me economically,” Kent said. “But there I was, a gay lawyer who was representing gay bars and gay friends and gay owners.”

Kent said that decades ago he never cared if people knew his sexual orientation. Once, a South Florida Sun Sentinel reporter interviewed Kent for a story and asked about rumors that he was gay — and then never published that he was.

“It’s not my job to do their thinking for them. It’s my job to be who I am. And I’m proud of every minute and moment of who I am and what I was,” Kent said. “And if that meant I was a faggot who could throw a baseball, that’s their problem.”

After he moved to South Florida, Norm Kent briefly wrote a column for Playbill magazine and taught sociology at Florida Atlantic University. Soon he became known locally as an advocate for runaway gay youths who hung out at Fort Lauderdale Beach.

On the strip, Kent interviewed 30 boys ages 12 to 20 working as prostitutes. By 1984, Kent had spoken with about 150 boys on the strip — a third of them said they had sold their bodies to survive.

For years, Fort Lauderdale police and politicians worked to downplay the local homeless problem, according to a 1989 Miami Herald profile of Kent headlined “Upholder of the Unpopular.”

“It was like the mayor in Amity denying that there was a shark out there,” Kent told the Herald, referring to the blockbuster 1975 film of the era, “Jaws.”

Kent spent the rest of his life advocating for homeless gay youth. In 2000 — after having just survived treatment for lymphoma — Kent met John Fugate, then 18 and disowned since middle school by his Lakeland family. Kent, who at the time published the Express Gay News in Fort Lauderdale, offered Fugate a job delivering newspapers.

“I was living under the bridge on Federal Highway just south of 26th Street,” Fugate said March 28, weeping, a few feet from Kent’s hospice bedside. “And Norman found out that I was sleeping on the street and he invites me to the Floridian Restaurant for dinner.”

That night, Kent told him: “I just want you to know if you ever need a place to stay, you can always stay at my house. Here are the keys.”

At first, Fugate said he was “too proud and scared” to come to Kent’s home. But a few weeks later, about 3 a.m. on a cold, rainy morning, Fugate showed up. Eventually, he moved in.

Despite their age difference, Kent, 53, and Fugate, 21, became partners. Seven years later, they ended their romantic relationship. But they remained close friends and continued to work together on and off. After Kent’s health began to decline in 2018, Fugate and his new husband Brian Swinford stepped in as Kent’s caregivers.

Fugate said Thursday that Kent died of a recently diagnosed lung cancer.

On April 10, Fugate posted on Facebook: “Sometimes you start to doubt your beliefs and wonder why it’s happening to good people and telling yourself why can’t the good people live in why does it have to be this way? I’m so lucky to have had Norm Kent in my life forever changed me to make me a better person, there’s no way on earth I could ever repay him or show him the love that I have for him other than being here for him now.”

Mark Possíen, Kent’s close friend since 1977, described his Victoria Park home as “a refuge for so many people.”

“If you were down and out, he would invite you to come and stay with him. He’d get you a job. If you were on drugs, he tried to get you off drugs,” Possíen said. “He was selfless. He did everything with no expectation of any kind or return or reward from the person.”

About 1991, Possíen moved into a spare room in the Victoria Park house where Kent helped him launch Catalog X, one of the first gay-owned mail-order adult toy businesses.

“I was Dildo Central!” Kent wrote in his final SFGN column published March 30.

By 1998, Possíen had opened two Catalog X retail stores, one in Fort Lauderdale, the other in South Beach. “It was a gay department store. We had everything we thought gay people would be interested in.”

Possíen, who closed Catalog X in 2003, now lives in Lake Worth. In late March, Kent told him that his “biggest disappointment” about having terminal cancer was not having enough time “to sue Ron DeSantis for the drag queen stuff.”

“He said, ‘I’ve taken on all these cases all my life, I didn’t make money on them and sometimes they cost me money,’” Possíen said. “When he saw something that was wrong or unjust, he wanted to fix it.”

During college on Long Island, Kent dabbled as a reporter writing for the local Jewish Journal and Nassau Herald.

Later in South Florida, Kent himself became a media celebrity.

“He’s lived his life in the public eye,” Kent’s brother Alan said. “Norman has done a lot of good stuff and he’s had a lot of recognition for what he accomplished.”

Norm Kent’s name frequently appeared in both the Sun Sentinel and the Miami Herald. Among his high-profile legal cases:

- Helping adult video store owners charged with obscenity in the 1980s.

- Representing the owners of nude dance clubs in the 1990s, when South Florida municipalities tried to shut them down.

- Defending countless men charged with public sex in restrooms, in parks and on beaches throughout South Florida well into the 2000s.

A 1992 case that got particular attention: When gay radio superstar Neil Rogers, Kent’s close friend, was charged with indecent exposure at an adult movie theater in South Beach.

“Millions” of other men were arrested under the same circumstances, Kent recalled March 28.

“Only straight men would go free. … And people like Neil would get into trouble. I said ‘What the hell is going on here? This isn’t right. This isn’t fair to gay people.’ Over the years, so many would be wrongfully and unjustly arrested and prosecuted.”

From 1989 to 1992, Kent had his own daily talk show on WFTL AM. Later, he hosted various radio programs including one broadcast live during the breakfast rush at the Floridian on Las Olas Boulevard.

He also represented Rogers in the radio business. “I wound up making him, as his agent, $1.5 million a year,” Kent said.

Kent said that for years, Rogers made fun of him on the radio and elsewhere, sometimes referring to him as “Norma.”

“Do you know that they gave me an award for donating money to the Broward General Cancer Society in 2000,” Kent recalled. “And they put my name up on a plaque. And one of the ladies who made the plaque, she really thought my name was Norma. She didn’t put ‘Norman Kent’ on the plaque. She put ‘Norma.’ I said, ‘Neil, you did that.’ We thought that was hilarious.”

In 1999, Kent took on a new title: Newspaper publisher. He launched the Express Gay News, which covered all aspects of queer life in South Florida.

Kent sold the paper four years later to Window Media, a national LGBT media group that renamed it the South Florida Blade. Window Media went bankrupt in November 2009 and quickly shut down the Blade. Most of the staff of the Blade reorganized and launched the Florida Agenda, which shut down in 2016.

In January of 2010 Kent launched a new newspaper and website called South Florida Gay News, along with a new business partner Piero Guidugli, who stayed with the company until 2020.

Celebrating 400 issues of SFGN in 2018, Kent and Guidugli highlighted a few of their most compelling stories, including:

- A five-year long program of entrapment by two West Palm Beach policemen who had entrapped more than 300 men.

- Hollywood police fired officer Mikey Verdugo in 2010 after the department learned he had appeared in a 15-minute gay porn scene 14 years earlier. (Verdugo now owns Bodytek Fitness in Davie and Wilton Manors.)

- The 2010 firing of licensed practical nurse Ray Fetcho AKA drag queen Tiny Tina, when it came out that 35 years earlier Fetcho had been charged with a lewd act for hosting a wet jockey shorts contest at the old Copa nightclub in Fort Lauderdale. (Fetcho died at 68 of cancer and diabetes in 2015.)

In 2016, Kent wrote in a publisher’s column about the last of the big gay bar raids in Broward County, when in 1991 then-Sheriff Nick Navarro created a media spectacle arresting men at the Copa and at Club 21 in Hallandale Beach.

“Sheriff Navarro orchestrated the raid as if he were hosting a Hollywood opening,” Kent wrote. “As the news report by Steve Rothaus indicates, the sheriff turned the raid into a media event, placing the entire LGBT community in a false light. Navarro arrived on the scene, believe it or not, in a helicopter, accompanied by his wife, dressed in an evening gown. Reporters were shocked by the crass celebration, amazingly accompanied by foreign Russian dignitaries to show off for.”

Kent said he never regretted publishing a story, even if it got him into hot water with local power figures, including activists and elected officials.

“It’s the newspaper. It’s what editorial cartoons are all about,” he said. “It’s not for the politician to be thin skinned. It’s for the politician to go naked before the canon and accept the fact that he, too, can be criticized no matter how good they think they are.”

The past five years, Kent suffered several life-threatening health setbacks. He had two brain surgeries to remove tumors, COVID in 2021 and then the pancreatic cancer diagnosis.

Last September, he stepped down as publisher and handed the running of SFGN to Associate Publisher Jason Parsley.

“Jason has established himself as a very powerful voice, not afraid to stand up to anybody,” Kent said March 28.

Parsley, 45, a one-time hair stylist who in 2007 got a journalism degree from Florida Atlantic University, has worked at SFGN since 2011.

These days, a local LGBT newspaper and website are more important than ever, Parsley said.

“Our stories, need to be told, must be told,” he said. “Unlike big corporate media, an LGBT paper is invested in the community.”

“You have a hostile legislature that wants to silence and erase our voices and stories. And because this isn’t taught in school, places like the gay media are where you are going to be informed and educated and learn about the queer community.”

Parsley said Kent “had a passion for journalism and being a storyteller.”

“He leaves a long legacy of journalism and a dogged pursuit of the truth,” Parsley said. “He wasn’t just a news reporter. He also wrote scathing and biting — truthful — editorials that would sometimes call out members of our own community and push the ball forward.”

Journalist Steve Rothaus covered LGBTQ issues for 22 years at the Miami Herald. @SteveRothaus on Twitter.

Norm Kent’s eloquence and outlook on life expressed in final column

Thirteen days before his passing, on March 30, South Florida Gay News published an opinion column written by Norm Kent entitled, “What is Hospice and What it Means to Me,” in which he movingly and eloquently described his outlook on life and his passion for journalism as noted by those who knew him.

“Last week, the doctors told me about a new and invasive cancer and tumor that would require even more sudden and maybe midnight trips to the ER and hospitals, ending the day with newer needles in my arms and weakening veins,” Kent wrote.

“Nope, no more,” he continued. “I think I have done my share for here and now. An activist for gay rights and your rights; for NORML and human rights. Your body. Your life. Your call. I hope I have made you proud.”

He reminisced about his life experiences and those dear to him along with loved ones who have been at his side during his illness before stating, “So folks, that all brings me to home health care hospice, like President Jimmy Carter has just done. It’s not to say goodbye, but to thank you for the many hellos. From the many memories; from your local hospitality establishments and homes and businesses.”

And in keeping with his philosophy on life, Kent concluded by saying, “Keep on doing what is right, remembering what is right is not always popular, and what is popular is not always right. You will always find a path belonging to you. Like Yogi Berra, New York Yankees Hall of Famer once said, ‘When you come to a fork in the road, take it.’ It’s your own. Forever.”

— Lou Chibbaro Jr.

Notables

Beloved LGBTQ+ philanthropist Bruce Bastian dies at 76

Bastian co-created a word-processing program which later became WordPerfect as a graduate student at Brigham Young University

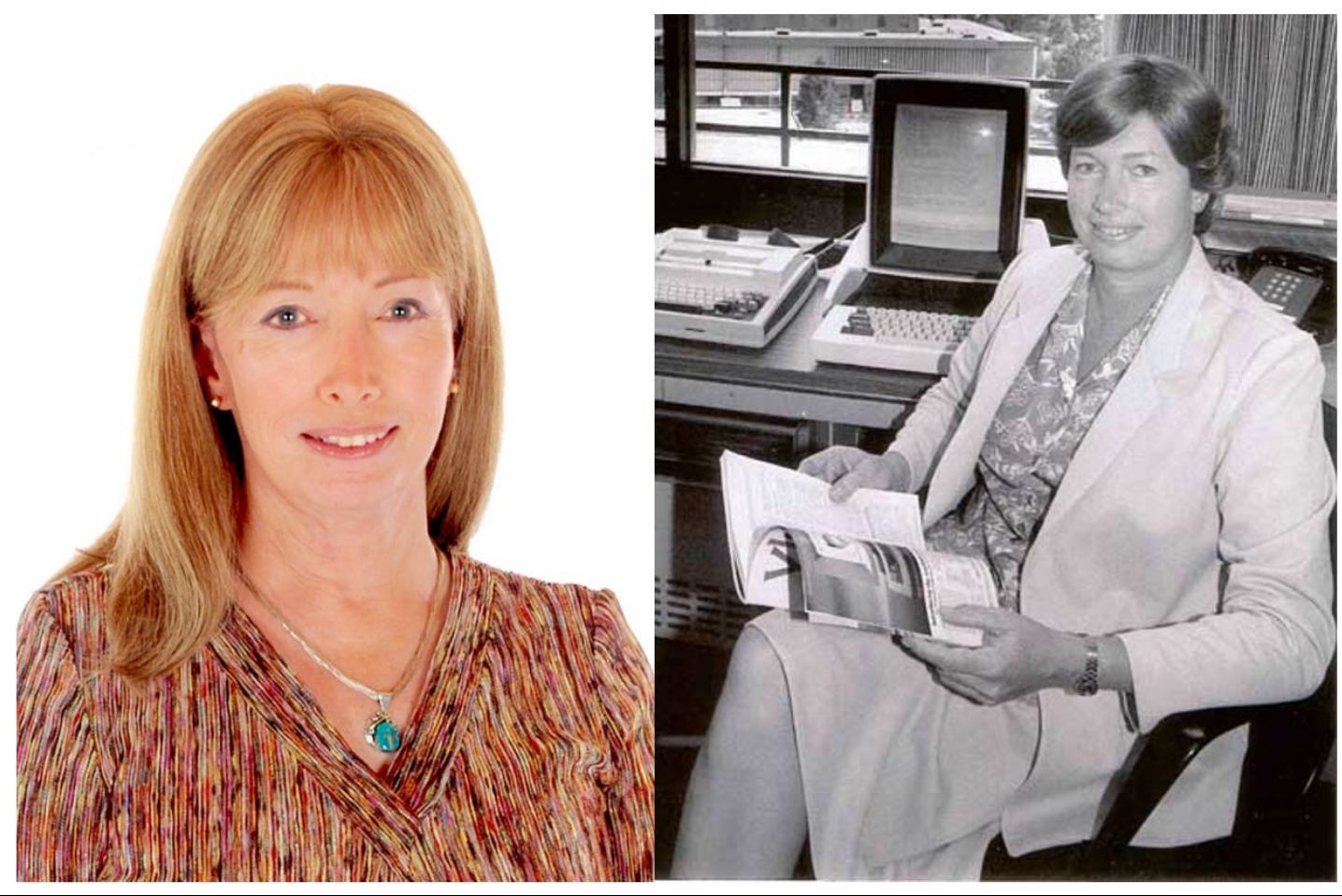

SALT LAKE CITY, Utah – Bruce Bastian, a successful Utah businessman and pioneering computer software developer who co-founded the word processing company WordPerfect before becoming a beloved philanthropist who donated millions of dollars to LGBTQ rights causes and the performing arts, passed away on June 16, according to an announcement by the LGBTQ organization Equality Utah.

“No individual has had a greater impact on the lives of LGBTQ Utahns,” Fox 13 TV News of Salt Lake City quoted Equality Utah Executive Director Troy Williams as saying. “Every success our community has achieved over the past three decades can be traced directly back to Bruce,” Williams was quoted as saying.

Fox 13 reported that Bastian co-created a word-processing program which later became WordPerfect as a graduate student at Brigham Young University with co-founder Alan Ashton, who was a Brigham Young computer science professor. The two developed the software under contract with the city of Orem, Utah, but they retained ownership of it, according to Fox 13.

“Bruce was definitely a legend, running one of the most successful companies, and an out and proud gay individual,” his friend David Parkinson said in a 2022 interview with Equality Utah, Fox 13 reports. “Not only does he give his money, but he gives his time, he gives his connections, he gives his knowledge, to help change Utah,” Parkinson told Equality Utah, of which Bastian was a founding member.

Fox 13 reports that among the organizations to which Bastian was a generous supporter and financial donor were the Utah AIDS Foundation, Utah’s Plan-B Theatre, the Utah Symphony and Opera and Ballet West, and the University of Utah.

A Wikipedia article on Bastian’s life and career says that in 2003, he donated more than $1 million to the Human Rights Campaign, the nation’s largest LGBTQ advocacy organization. It says he donated $1.7 million in 1997 for the renovation of the University of Utah’s Kingsbury Hall in 2000 donated $1.3 million to support the university’s purchase of 55 Steinway pianos. The article says he also supported the university’s LGBTQ Resource Center on campus.

Both Fox 13 and Wikipedia report that in 2010 President Barack Obama appointed Bastian to the Presidential Advisory Committee of the Arts.

Wikipedia, citing the OUTWORDS archive, reports that Bastian was born March 23, 1948, in Twin Falls, Idaho, was raised as a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, and served as a missionary in Italy. It says he received a bachelor’s degree in music and a master’s degree in computer science from Brigham Young University. As an undergraduate, he served as director of the university’s Cougar Marching Band, the article says.

It says Bastian married Melanie Laycock in 1976 and the couple had four sons before they divorced in 1993. It says Bastian later married Clint Ford.

“Bruce’s impact reached far beyond Utah, as a leading supporter of the national marriage equality movement, and a major benefactor and board member of the Human Rights Campaign,” the Equality Utah statement says, as reported by Fox 13. “He has been a rock and pillar for all of us,” the statement continues.

“Our community owes more to Bruce than we can possibly express,” it says. “We send our love, gratitude and condolences to Bruce’s wonderful husband Clint, and his friends and children.”

In a statement released on Monday, HRC said Bastian joined the HRC board in 2003. It says the following year he joined fellow HRC board member Julie Johnson to serve as co-chair of “the board’s successful effort to help defeat the Federal Marriage Amendment, a proposed amendment to the constitution that would have specified marriage as legal only between a man and a woman.”

The HRC statement says Bastian passed away peacefully “surrounded by his four sons, his husband, Clint Ford, and friends and other family members.” The HRC and Equality Utah statements did not disclose a cause of death.

“We are devastated to hear of the passing of Bruce Bastian, whose legacy will have an undeniably profound impact on the LGBTQ+ community for decades to come,” said HRC President Kelley Robinson in the HRC statement. “Bruce was in this fight, working at every level of politics and advocacy, for over here decades,” Robinson said.

“He traveled all across this country on HRC’s behalf and worked tirelessly to help build an inclusive organization where more people could be a part of this work,” she said. ‘Bruce stood up for every one of us and uplifted the beautiful diversity of our community,” Robinson said. “It’s the kind of legacy we should all be proud to propel forward.”

The HRC statement says that in addition to his four sons, Bastian is survived by 14 grandchildren, two sisters, a brother, and numerous other extended family members.

Notables

Pete & Chasten Buttigieg on fatherhood

He’s a Harvard grad, Navy veteran, Mayor of South Bend, Ind. & Secretary of Transportation, but Pete Buttigieg has another title: Papa

By Jonathan Vigliotti | (CBS Sunday Morning) TRAVERSE CITY, Mich. – When it comes to handling a pair of toddlers, Pete Buttigieg, the unflappable Secretary of Transportation, may appear a little jet-lagged. Pete and his husband, Chasten Buttigieg, raise their two-year old twins, Penelope and Gus, in Traverse City, Michigan, where they recently moved full-time from Washington to be closer to family.

The kids call Pete “Papa,” and Chasten “Daddy.”

He’s a Harvard grad, Rhodes scholar, Navy veteran, Mayor of South Bend, Ind., presidential candidate, and Secretary of Transportation, but Pete Buttigieg has another title: Papa. He and husband Chasten Buttigieg share with correspondent Jonathan Vigliotti their journey to parenting twins Penelope and Gus.

Watch:

Notables

Pioneering trans computer scientist Lynn Conway dies at 86

If you are reading this on your mobile phone, you owe it to Conway who pioneered the microchip technology that makes it possible

By Erin Reed | ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Yesterday, news broke that transgender woman and computer pioneer Lynn Conway passed away at the age of 86. Her story is nothing short of remarkable.

Conway helped pioneer early supercomputers at IBM but was fired after she transitioned. She went “stealth” and had to rebuild her career from the ground up, starting as a contract programmer at Xerox with “no experience.”

Then, she did it all over again, pioneering VLSI—a groundbreaking technology that allowed for microchips to be made small enough to fit in your pocket, paving the way for smartphones and personal computers. In 1999, she broke stealth, becoming an outspoken advocate for transgender people.

Conway first attempted to transition at MIT in 1957 at the age of 19 years old. At the time, the environment was not accepting enough for transgender people to do so. She would have faced enormous barriers to medical transition, as few doctors were knowledgeable enough to prescribe hormone therapy a the time. Like many transgender people seeing enormous barriers to care, she spent the following years closeted.

Eventually, she was hired by IBM where she helped develop the world’s fastest supercomputer at the time on the Advanced Computing System (ACS) project. The computer would become the first to use a “superscalar” design, which made it capable of performing several tasks at once, dramatically improving its performance and making it much faster than previous computers. Despite her pivotal role in the project, she was fired when she informed her employer that she wanted to transition.

What she did next is nothing short of remarkable. Realizing that as an openly transgender woman in 1968, few companies would hire her, she went “stealth” and pretended she had no significant prior experience in computers.

She quickly advanced through the ranks and was hired by Xerox, where she famously developed VLSI, or Very Large Scale Integration. This groundbreaking technology allowed for thousands of transistors to be packed onto a single chip, revolutionizing electronics by making cell phones and modern computers possible through miniaturization and increased processing power.

Conway didn’t stop there. After gaining fame for her computer innovations, she came out in 1999 to advocate for transgender people. She was among the early critics of Dr. Kenneth Zucker, an anti-trans researcher still cited today by those working to ban gender-affirming care.

Conway slammed Zucker for practicing “reparative therapy,” a euphemism for conversion therapy. Notably, Zucker’s research continues to make false claims that “80% of transgender kids desist from being trans,” numbers based on his clinic’s practices, which closely mirrored gay conversion therapy. That clinic has since been shut down over those practices.

Often, those opposed to transgender people paint a picture of gender transition as something new, unique, or unsustainable. Similarly, many who transition are told they cannot be successful as transgender individuals.

Such claims are often weaponized by anti-trans activists like Matt Walsh, who once mockingly asked, “What exactly have ‘transgender Americans’ contributed?” Conway’s life was a resounding rebuke to these attacks. She attempted to transition at a young age in the 1950s, revolutionized computing twice from scratch, and made the cell phone Walsh likely used to post such a question possible.

Perhaps more importantly, Conway’s life gave transgender people another gift: a visible example that we can grow old, and a reminder that we have always been here. In a world where so many of us have had to hide in silence or stealth, where representation has been denied, and where we are told that our lives will be too dangerous to live, Conway proved that one can be trans and live a long, fulfilling, and proud life.

Related:

******************************************************************************************

Erin Reed is a transgender woman (she/her pronouns) and researcher who tracks anti-LGBTQ+ legislation around the world and helps people become better advocates for their queer family, friends, colleagues, and community. Reed also is a social media consultant and public speaker.

******************************************************************************************

The preceding article was first published at Erin In The Morning and is republished with permission.

Notables

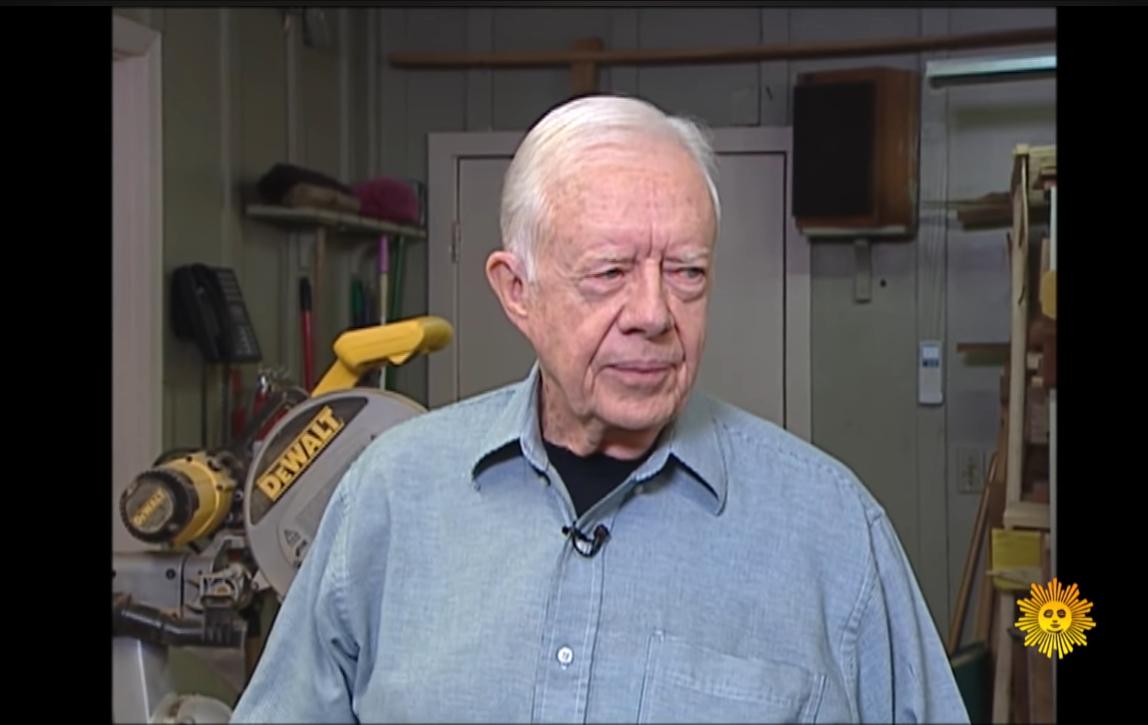

Jimmy Carter’s grandson believes his granddad nearing the end

“There’s a part of that faith journey that you only can live at the very end. And I think he has been there in that space”

By Jill Nolin | ATLANTA, Ga. – The grandson of former President Jimmy Carter provided an update on his grandfather’s condition Tuesday at the Rosalynn Carter Symposium on Mental Health Policy, which was the first held since the former first lady’s death.

Grandson Jason Carter said he visited his grandfather at his home in Plains a couple weeks ago to watch an Atlanta Braves baseball game.

“I said, ‘Pawpaw, people ask me how you’re doing, and I say, I don’t know.’ And he said, ‘well, I don’t know myself,’” Jason Carter said during the event at the Carter Center in Atlanta. “He’s still there.”

Jimmy Carter, who at 99 years old is the longest lived president, has been in hospice care since early 2023. Rosalynn Carter, his wife of 77 years, died in November.

Jason Carter said he believes his grandfather is nearing the end.

“There’s a part of this faith journey that is so important to him, and there’s a part of that faith journey that you only can live at the very end. And I think he has been there in that space,” Jason Carter said.

His grandfather’s time in hospice care has been a reminder of the work Rosalynn Carter did to advance caregiving and mental health, he said.

“The caregiving associated with mental health and mental illness is so crucial and so fundamental to the work that we all do in this room and to her legacy that it is remarkable and important, and we’ve all experienced it very first hand over the last year so we give thanks for that as well,” Jason Carter said.

******************************************************************************************

Jill Nolin has spent nearly 15 years reporting on state and local government in four states, focusing on policy and political stories and tracking public spending. She has spent the last five years chasing stories in the halls of Georgia’s Gold Dome, earning recognition for her work showing the impact of rising opioid addiction on the state’s rural communities. She is a graduate of Troy University.

******************************************************************************************

The preceding article was previously published by the Georgia Recorder and is republished with permission.

The Georgia Recorder is an independent, nonprofit news organization focused on connecting public policies to the stories of the people and communities affected by them. We bring a fresh perspective to coverage of the state’s biggest issues from our perch near the Capitol in downtown Atlanta. We view news as a vital community service and believe that government accountability and transparency are valued by all Georgians.

We’re part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization.

Notables

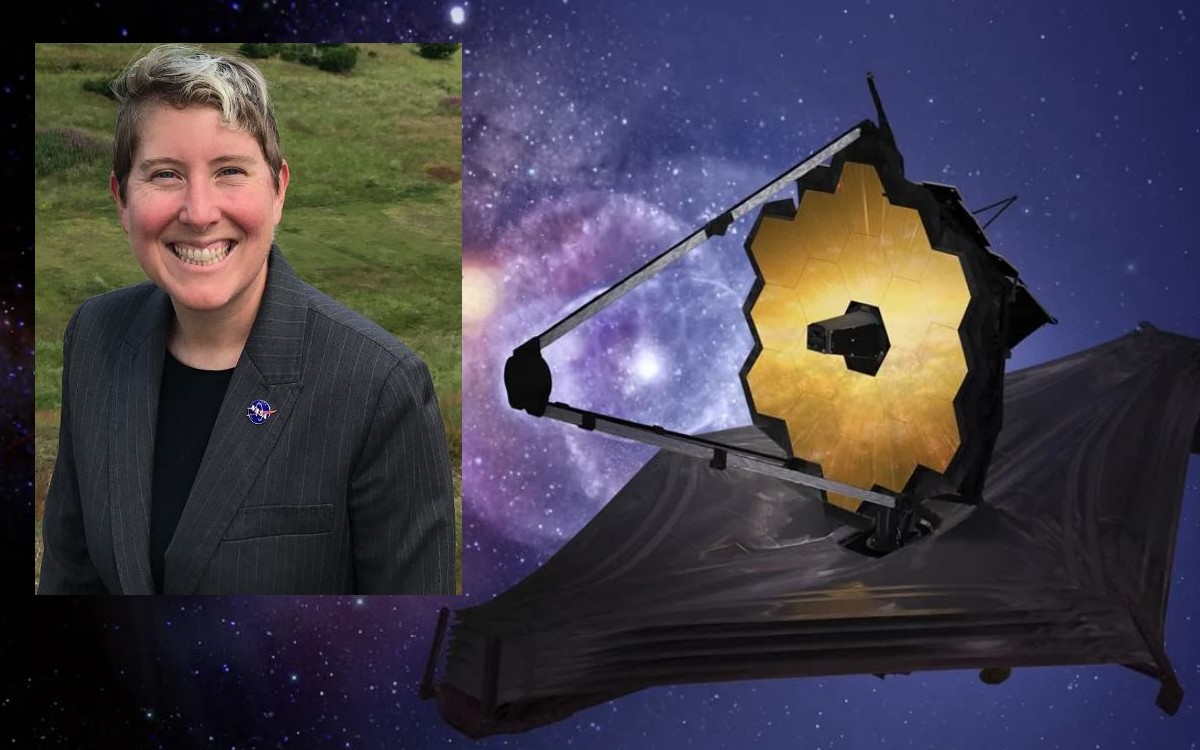

Astrophysicist Jane Rigby awarded Presidential Medal of Freedom

Rigby, a married out lesbian & mom, is the chief scientist of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, the world’s most powerful telescope

WASHINGTON – Sitting among a diverse and venerable group of Americans from every walk of life on the dais in the East Room of the White House on Friday was out lesbian and NASA astrophysicist Jane Rigby, awaiting her turn to be honored by President Joe Biden who would bestow the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, on her.

Rigby, an astronomer who grew up in Delaware, is the chief scientist of the world’s most powerful telescope who alongside her team operating NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, studies every phase in the history of the Universe, ranging from the first luminous glows after the Big Bang, to the formation of solar systems capable of supporting life on planets like Earth, to the evolution of the Solar System.

A member of Penn State’s Class of 2000, Rigby graduated with a bachelor’s degrees in Physics and Astronomy. She also holds a master’s degree and a PhD in Astronomy from at The University of Arizona. Her work as the senior project scientist for NASA’s Webb Telescope includes studies on how galaxies evolve over cosmic time and she has published more than 140 peer-reviewed scientific papers.

Rigby was named to Nature.com’s 2022 list of 10 individuals who shaped science and to the BBC’s list of 100 inspiring and influential women in the same year. Rigby had postdoctoral fellowships at Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena CA before landing her job at Goddard. In 2013 Dr Rigby was awarded the Robert H. Goddard Award for Exceptional Achievement for Science.

A founding member of the American Astronomical Society’s Working Group on LGBTQ Equality (WGLE) in January 2012, now called the Committee for Sexual-Orientation & Gender Minorities in Astronomy (SGMA), Rigby serves as its Board Liaison until her term expires this June.

The out lesbian astrophysicist in an interview for SGMA’s website spoke about her experiences including coming out:

“I’ve been out since 2000. My story’s simple — I fell in love with a fellow grad student in the department. It was a close-knit department, so hiding would have been ludicrous. Nor did I want to hide the best thing in my life! So, we were out as grad students. I certainly heard people say awful homophobic things at work there. They weren’t directed at me, and they weren’t said by people with power over me. If I recall, I was much less afraid of homophobic discrimination at work, than I was afraid of the two-body problem, and the lack of support we would receive as a same-sex couple in astronomy. That fear turned out to be justified. I’ve seen numerous different-sex couples get a wide range of support in solving the two-body problem, which was never offered to us,” she told the interviewer.

She reflected on American astronaut and physicist Sally Ride, her childhood role model who had an impact on her career:

“One of my biggest role models when I was young was Dr. Sally Ride. A few years ago, on her deathbed, Dr. Ride chose to write in her obituary that her life partner had been a woman. Dr. Ride was the most influential woman scientist when I was growing up — the person that made me say, “I want to do THAT when I grow up.” It was because of her that I realized that astrophysics was a profession, that physics was a subject girls could study, that NASA needed astrophysicists. So I’m so… amused, I suppose, that Sally Ride was this influence on my life’s path, at a time when I was completely unaware that it was even possible to *be gay* — and at the same time, she was gay, in love, and deeply closeted to keep her job.”

The interviewer noted that “for some women being gay is a cause for concern at the work place. Some say they were unsure about how to turn their sexual orientation into a positive aspect of their work persona.” Then asked Rigby What is your view on this?

“My experience is that absolutely I am a *better* astronomer because I’m queer. For a few reasons. First, I see things different than my colleagues. On mission work, as we weigh a decision, my first thought is always the community impact: “If we do things this way, who benefits, and who gets left out in the cold?” Will this policy create inclusion, or marginalization? I think about science in terms of community-building. What team do we need to tackle a given science problem, with skills that are different from mine? Absolutely I think that way because I’m an outsider, because I’ve been marginalized. And because community-building is central to LGBTQ culture,” she said.

Editor’s note: You can read Rigby’s complete SGMA interview here: (Link)

Married to Dr. Andrea Leistra, Rigby, her wife and their young child reside in Maryland not far from her workplace at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in suburban Washington D.C. and when not studying the universe is often found on the neighboring Chesapeake Bay wind boarding, a favored pastime.

Also honored in the ceremony Friday were a former U.S. Vice-President, a civil rights worker and martyr, two former cabinet secretaries- one a former U.S. Secretary of State, a speech writer for the late Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., an Olympian and gold medalist, and one of the most powerful woman political leaders and the Speaker Emeritus of the U.S. House of Representatives, among others, and LGBTQ+ advocate Judy Shepard.

Watch:

Notables

Ella Matthes, publisher of Lesbian News Magazine, dies at 81

Longtime publisher and editor of Lesbian News Magazine, Matthes successfully ran Lesbian News Magazine from 1994 until 2022

LOS ANGELES – Ella Matthes, longtime publisher and editor of Lesbian News Magazine, passed away from a heart attack on March 16, 2024 at The Little Company of Mary hospital in Norwalk, California. She was 81 years old.

Matthes successfully ran Lesbian News Magazine from 1994 until 2022. The Lesbian News, more commonly known as the LN, had the distinction and responsibility of being North America’s longest running lesbian publication. Founded in 1975 in Southern California by Jinx Beer, LN began as the lone voice for lesbian issues and evolved throughout the years under Matthes’ leadership to become the nation’s foremost voice for lesbians of all ages.

Some of the iconic cover stories have included names such as Melissa Etheridge, kd lang, Ellen DeGeneres, Marlee Matlin, Hillary Clinton, Toni Braxton, Lady GaGa, Katy Perry, Judith Light, and Janet McTeer.

Her numerous contributions to the LGBTQ+ community earned her a slew of recognitions and awards. She was the recipient of the 2002 Women’s Night Gay & Lesbian Center’s “Lesbian & Bisexual Women Active in Community Empowerment Award;” the 2002 “Business Alliance of Los Angeles Community Involvement Award;” the 2003 Southern California Women for Understanding “Community Service Award;” and the 2012 Vox Femina Los Angeles “Aria Award.”

A native of Los Angeles, California, Matthes graduated from Dorcey High School and attended UCLA for a brief period. She played the saxophone in high school and was a competition bowler for many years.

At the young age of fifteen, she went to work at Great Western Savings in the print shop and developed a passion for printing. By the time she was in her twenties, she purchased Superior Printers and ran it for decades. However, something else kept tugging at her heartstrings. Ella felt lesbians weren’t receiving a lot of support and visibility and wanted to do something about it. So, in 1994, she purchased Lesbian News Magazine from Deborah Bergman who had acquired it from its original owner, Jinx Beers.

Ella Matthes built a mission statement around her vision for all lesbians. “The editorial vision of the LN has always been to inform, entertain, and be of service to women who love women of all ages, economic class, and color. We hope women from all walks of life will not only find something of themselves in the LN, but also be accepting of those with differing opinions. Lesbian News is our small contribution to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender liberation movement.”

She is survived by her brother Carl Matthes and her wife Gladi Adams. Ella and Gladi had been together for 26 years and married July 13, 2013.

Donations in her name can be made to the June Mazer Archives in West Hollywood, CA.

Notables

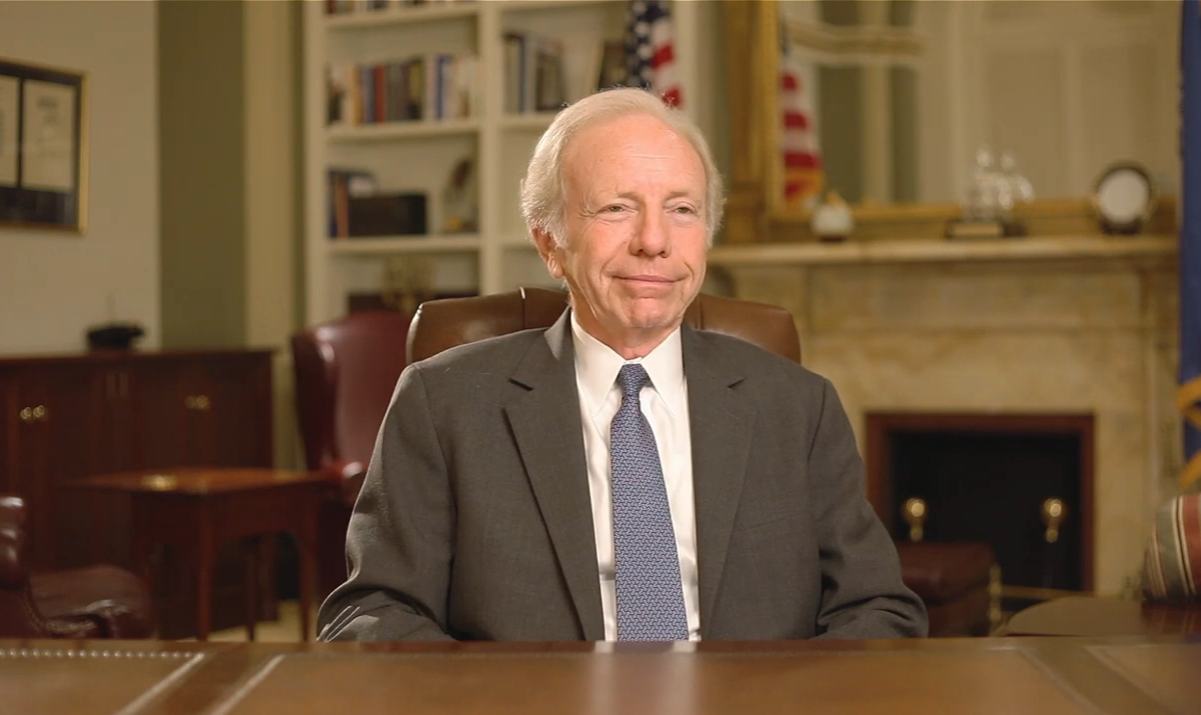

Former Connecticut U.S. Senator Joe Lieberman dies at 82

Lieberman co-introduced & championed Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal Act of 2010, expressed support for abortion rights & environmental causes

NEW YORK – Former U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, who had served first as a longtime Democratic Senator and then declared himself an independent winning reelection in 2006, died Wednesday, March 27, 2024, at New York-Presbyterian Hospital due to complications from a fall. He was 82 years old.

The announcement of his death was released by Lieberman’s family and noted “his beloved wife, Hadassah, and members of his family were with him as he passed. Senator Lieberman’s love of God, his family, and America endured throughout his life of service in the public interest.”

Lieberman, who nearly won the vice presidency on the Democratic ticket with former Vice-President Al Gore in the disputed 2000 election and who almost became Republican John McCain’s running mate eight years later, viewed himself as a centrist Democrat, solidly in his party’s mainstream with his support of abortion rights, environmental protection, gay rights and gun control, The Washington Post reported.

The Post added that Lieberman was also unafraid to stray from Democratic orthodoxy, most notably in his consistently hawkish stands on foreign policy.

Lieberman was first elected to the United States Senate as a Democrat in 1988. He was also the first person of Jewish background or faith to run on a major party Presidential ticket.

In 2009 he supported The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which was passed as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 on October 22, 2009 and then was signed into law on the afternoon of October 28, by President Barack Obama.

Lieberman, who served in the Senate for more than two decades, alongside with Susan Collins (R-Maine), were the original co-sponsors of the legislation in the successful effort to repeal the Pentagon policy known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” which barred open service by gay and lesbian servicemembers in 2011.

Lieberman said the effort to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in Congress was one of the most satisfying and thrilling experiences he’s had as a senator.

“In our time, I think the front line of the civil rights movement is to protect people in our country from discrimination based on sexual orientation — all the more so when it comes to the United States military, whose mission is to protect our security so we can continue to enjoy the freedom and equal opportunity under law,” Lieberman said.

In an statement to the Blade Wednesday afternoon, David Stacy, the Human Rights Campaign Vice President for Government Affairs said:

“Senator Lieberman was not simply the lead Senate sponsor of the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell — he was its champion, working tirelessly to allow lesbian, gay, and bisexual people to serve in the military as their authentic selves. The nation’s first Jewish Vice-Presidential nominee, Lieberman had a historic career and his unwavering support for lesbian, gay, and bisexual military servicemembers is a powerful legacy. Our hearts go out to his family and friends as they grieve a tremendous loss.”

In September of 2011, during a press conference marking the repeal of the Pentagon policy, questions emerged about how to extend greater benefits to LGBT service members.

In addition to the legislation that would repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” reporters asked lawmakers about legislation in the Senate known as the Respect for Marriage Act which was aimed at the repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act, which prohibited same-sex marriage. Collins and Lieberman weren’t co-sponsors of that legislation.

Collins had left the news conference at the start of the question-and-answer period. In response to a question from the Washington Blade, Lieberman offered qualified support for the Respect for Marriage Act.

The Connecticut senator said he had issues with the “full faith and credit” portion of the Respect for Marriage Act enabling federal benefits to flow to married gay couples even if they live in a state that doesn’t recognize same-sex marriage.

“I do support it in part — I think we’ve got to celebrate what we’ve done today — I certainly support it in regard to discrimination in federal law based on sexual orientation,” Lieberman said.

That issue became a mute point after June 26, 2015 when in a landmark decision of the Supreme Court, Obergefell v. Hodges, justices ruled that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.

Lieberman by that time however, had retired from the U.S. Senate. He announced he would not seek another term on December 12, 2012 and left the Senate the following year. He was succeeded by Democratic representative Chris Murphy.

Following his retirement from the Senate, Lieberman moved to Riverdale, the Bronx, and registered to vote in New York as a Democrat.

In 2024 Lieberman was leading the search to find a presidential candidate for the third-party group No Labels to run against former President Trump and incumbent President Joe Biden, who he had served with in the Senate.

In a post on X (formerly Twitter) former President Barack Obama paid tribute to Lieberman:

“Joe Lieberman and I didn’t always see eye-to-eye, but he had an extraordinary career in public service, including four decades spent fighting for the people of Connecticut. He also worked hard to repeal “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” and helped us pass the Affordable Care Act. In both cases the politics were difficult, but he stuck to his principles because he knew it was the right thing to do. Michelle and I extend our deepest condolences to Hadassah and the Lieberman family.”

Joe Lieberman and I didn’t always see eye-to-eye, but he had an extraordinary career in public service, including four decades spent fighting for the people of Connecticut. He also worked hard to repeal “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” and helped us pass the Affordable Care Act. In both…

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) March 27, 2024

Lieberman’s funeral will be held on Friday, March 29, 2024, at Congregation Agudath Sholom in his hometown of Stamford, CT. An additional memorial service will be announced at a later date.

Notables

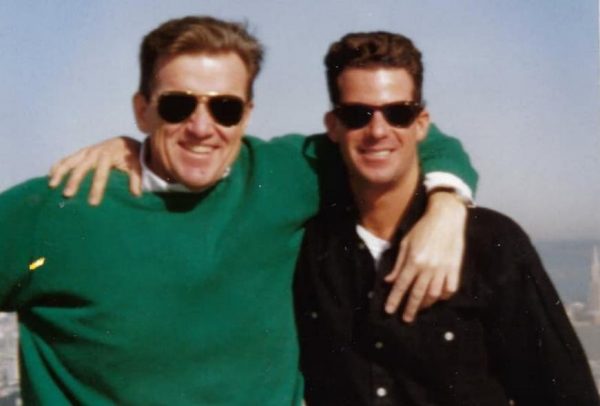

Iconic LGBTQ & AIDS activist David Mixner dies at 77

Mixner was a formidable presence in both Democratic progressive political circles and within his beloved LGBTQ+ community

NEW YORK – One of the most influential LGBTQ and HIV/AIDS activists and political strategists in the LGBTQ movement has died. David Benjamin Mixner, 77, was a longtime formidable presence in both Democratic progressive political circles and within his beloved LGBTQ community.

In a Facebook post on his personal page late Monday a simple statement read: “It is with a heavy heart that I share the news of David’s passing today.” News of Mixner’s death quickly spread as friends, longtime political acquaintances, and people whose lives he had impacted commenced to populate his page and others with reflections on his impact.

Neil Giuliano, the first directly elected openly gay mayor of a large city in the U.S. as mayor of Tempe, Ariz., who then went on to serve as president of GLAAD and later headed the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, was a longtime friend of Mixner. He wrote:

“We said goodbye in NYC on Feb 19, knowing time was short. Today my dear friend, confidant, and father figure for the last 28 years (though only 11 years my senior) has passed on from his earthly presence with us. He will absolutely “rest in power, for the cause of peace”.

(Photo via Giuliano/Facebook)

David Mixner contributed to my 1994 campaign for mayor even before we met. When I asked a local gay activist why this monumental LGBT figure was interested in donating to the closeted candidate in AZ, because I hadn’t done anything for gay rights, I was told “he knows you will.”

And boy, I don’t know how, but he knew me better than I knew myself; back then, and to this day.

[…] The two and half hours we shared on Feb 19th will forever remain among the most profound and powerful of my life, we covered it all. While preparing for death, David, one final time, taught and inspired me forward in life. ![]()

![]()

![]() “

“

Biographical write-ups on Mixner, including the archives of the LGBTQ history publication Outwords, show he was born and raised in the small town of Elmer, N.J.

While in high school he first became involved in social justice causes by supporting the civil rights movement and joining local protest rallies in support of racial justice.

After graduating from high school, he went to Mississippi to join civil rights protests organized by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other southern civil rights activists. In 1964, he enrolled as a student at Arizona State University, where he became involved in local union organizing before leaving Arizona to enroll in the University of Maryland, according to Outwords.

In 1968, he went to Chicago to join anti-Vietnam War protesters outside the Democratic National Convention, and according to his own account, was beaten by police that led to a leg injury that required his use of a cane for many years.

“He fought to end the War in Vietnam, and eventually landed in Los Angeles, where he helped to form Municipal Elections Committee of Los Angeles (MECLA), the nation’s first gay and lesbian political action committee,” Outwords reported. “Soon after, David helped defeat California’s potentially disastrous Proposition 6, which would have made it illegal for homosexuals to teach in public schools, by getting then-Governor Ronald Reagan to come out publicly against the measure,” which voters defeated by a wide margin.

The Washington Blade reported on Mixner’s support for Bill Clinton’s election as president in 1992 in his role as a friend of Clinton during the days when the two planned protests against the Vietnam War. Mixner, who raised money for the Clinton campaign and helped line up support for the then Arkansas governor from LGBTQ organizations throughout the country, was named by the Clinton campaign to serve on the campaign’s leadership committee.

But soon after Clinton’s election, Mixner spoke out against the new president’s decision to break his promise to issue an executive order to lift the ban on gays, lesbians, and bisexuals from serving in the U.S. military. Many LGBTQ activists, while disappointed, said Clinton was forced to support the controversial compromise of ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ after military leaders, including the popular Army Gen. Collin Powell, came out against lifting the ban, with both Democratic and Republican members of Congress also speaking out against a full lifting of the ban.

Mixner drew national attention when he helped organize a protest against ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ outside the White House in which he was among those arrested after denouncing his onetime friend Clinton for backing the policy. News of Mixner’s public break with the president resulted in the downfall of his once thriving political consulting firm.

“David’s political consulting career was over, and by the end of the Clinton presidency, he was pawning his watches to pay rent,” Outwords reported.

But Outwords and other publications and LGBTQ advocates have said Mixner re-invented himself many times, as a champion LGBTQ rights advocate, an author, performer, and organizer of the 2009 Equality March on Washington for LGBTQ rights that drew more than 200,000 participants from across the country.

His 2017 play, entitled 1969, was staged at a popular theater in New York City and received positive reviews. His one-man play in 2018 called ‘Who Fell into The Outhouse’ also received positive reviews and raised $175,000 for homeless LGBTQ youth, Outwords reported.

Mixner has also been praised for his longtime role as an AIDS activist who for many years helped raise funds for organizations supporting people with HIV/AIDS. In 1987, he joined one of the first HIV/AIDS protests outside the White House during the Reagan administration and was among more than 60 of the protesters arrested.

Among his many LGBTQ rights endeavors, Mixner is also credited with co-founding in 1991 the Gay and Lesbian Victory Fund, now called the LGBTQ+ Victory Fund, which became the nation’s first organization to devote all of its efforts to help elect LGBTQ people to public office.

“With support for candidates underway, his vision of a government and democracy representative of its people expanded beyond elections, and moved to ensure we were represented in political parties and presidential administrations as well,” said Victory Fund President and CEO Annise Parker in a statement responding to Mixner’s passing.

“Today, we lost David Mixner, a founding father of LGBTQ+ Victory Fund and our movement for equality,” Parker said. “David was a courageous, resilient, and unyielding force for social change at a time when our community faced widespread discrimination and an HIV/AIDS crisis ignored by the political class in Washington, D.C.,” Parker’s statement says.

“David gave his time, energy and money to building a new political reality in America – having the foresight and dedication to see it through in the most difficult times,” Parker states. “David embodied the spirit of activism and resistance in everything he did – and always with humor and a smile. He has changed not just America, but the world.”

Jeremy Bernard, a prominent Democratic fundraiser and gay rights advocate who served for eight years on the Democratic National Committee and served in the Obama-Biden administration as the White House social secretary wrote in his tribute to his friend with a photo on March 4:

“My dear friend has always been there for me and so many others! Love ya David!”

(Jeremy Bernard/Facebook)

In September of 2023, Mixner traveled from his home in New York City to Rehoboth Beach, Del., to attend an event in which he was honored for lending his name to an LGBTQ student scholarship created by CAMP Rehoboth, the LGBTQ community services center.

CAMP Rehoboth officials said they wanted to honor Mixner’s legacy with the David Mixner LGBTQ+ Student Scholarship, an endowed fund that supports students as interns at CAMP Rehoboth, where they do important work for the LGBTQ community.

“David changed the world forever and equality would not be where it is today without his leadership, passion, and immense heart and humor,” said GLAAD President and CEO Sarah Kate Ellis. “David was a beloved mentor to me and so many other LGBTQ leaders, always pushing for more for our community. He dedicated his life to our community and now we must strive to live up to his legacy.”

On Tuesday, the Ali Forney Center, a New York City-based organization that provides services and support for homeless LGBTQ youth, announced it has created the David Mixner Memorial Fund “to honor the life and legacy of this legendary fighter.”

Javi Morgado, a member of the Ali Forney Center board and a longtime friend of Mixner, said in a statement that Mixner raised more than $1 million for the organization since its founding in 2002.

“David’s final wish was that donations be made in his honor to this fund to support and protect LGBTQ+ youth from the harms of homelessness,” Morgado said. “I can think of no better way to honor the impact of our friend David than through activism and philanthropy,” he said, adding that donations can be made at aliforneycenter.org.

A funeral service will be held at 10 a.m. on March 25 at Church of St. Paul the Apostle, 405 W. 59th St., New York.

Addition reporting from Lou Chibbaro Jr.

Related:

Notables

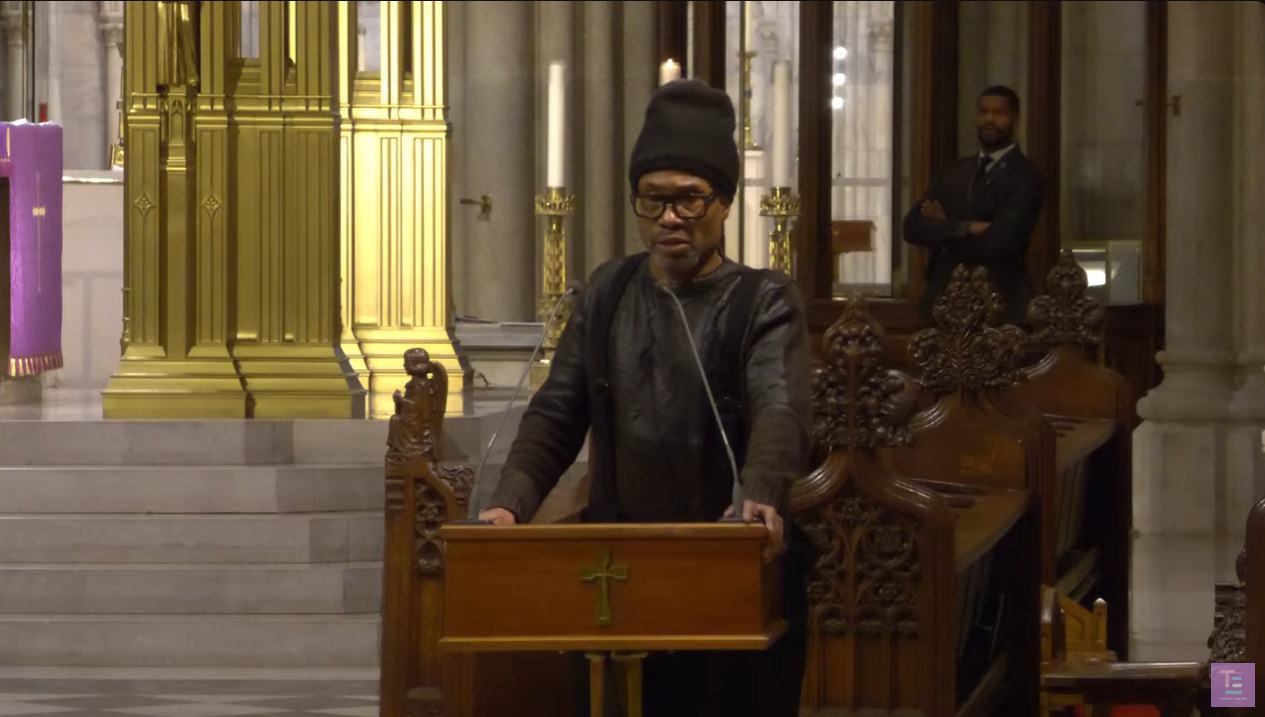

Cecilia Gentili’s funeral service held at St. Patrick’s Cathedral

Gentili was a legendary organizer, author, advocate, performer, and community icon. Her legacy endures on both systemic and personal levels

NEW YORK – The funeral services both somber and celebratory for Cecilia Gentili, a history-making trans activist, were held at New York City’s historic St. Patrick’s Cathedral Thursday. It is believed that Gentili is the first out transgender person and outspoken sex worker to have their funeral services at the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Patrick’s, which has historically not been a friendly institution to the LGBTQ+ community.

Over 1400 mourners came to memorialize and honor Gentili at St. Patrick’s in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It is the seat of the Archbishop of New York as well as a parish church.

Gentili tragically died on February 6th, just a week after her 52nd birthday. Her funeral service was both somber and celebratory of Gentili’s lasting impact on the community in New York City and across the country, with mourners chanting “Cecilia” in her honor.

Gentili was a legendary organizer, author, advocate, performer, and community icon. As the founder of Transgender Equity consulting and a beloved mother to countless queer, trans, and immigrant individuals in New York City, her legacy endures on both systemic and personal levels.

The vibrant ceremony included a performance from actor Billy Porter and speeches from chosen family, including trans activists Ceyenne Doroshow, Liaam Winslet, and Gentili’s partner, Peter Scotto. Notably, celebrities in attendance included, Sara Ramirez, Indya Moore, Peppermint, Raquel Willis, Ryan McGinley, and more.

“She was an angel,” said her partner, Peter Scotto. “Seeing all the people at the funeral services, and all the love I’ve received from people in her community all over the world, is a testament of how awesome Cecilia was. I’m so grateful for them all. She was an angel, an icon, a mother, an educator, a leader, and so much to so many people. Her children from AIPACHA, I’d hear all the stories of trans kids getting hormones for the first time. Our phone would ring all the time in the middle of the night and she’d jump into action to help people in crisis. She’d always be there and answer that call. But to me, she was my partner. We woke every day next to each other with so much laughter and love. I’m going to take that with me forever.”

Gentili came to New York as an undocumented immigrant from Argentina in 2004 and received citizenship via asylum in 2012. Her social justice efforts, which included advocacy for immigrant, HIV/AIDs, trans, and sex worker rights. Gentili changed the landscape in New York City and State and had ramifications across the country, including as the main plaintiff on a lawsuit against the Trump Adminstration’s attempt to eliminate healthcare protections for trans people. She had the ears of politicians at every level of government, as shown by the numerous elected officials’ public statements, including Governor Kathy Hochul, and a speech from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez on the house floor, in the aftermath of her death.

“Cecilia Gentili leaves a blazing legacy of love, kinship, and an infinite fire to uplift the liberation of trans people, sex workers, immigrants, and those pushed to the margins,” read a statement from Trans Equity Consulting, the organization founded by Cecilia Gentili. “Her mission to fully decriminalize and honor sex work continues through her namesake program Cecilia’s Occupational Inclusion Network (C.O.I.N.) Clinic, which provides free healthcare to sex workers in NYC, and the Stop Violence in The Sex Trades Act (SVSTA) in NY State –– a crucial piece of legislation that Governor Hochul could herald to truly honor Cecilia’s legacy. Cecilia, a fervent believer in action and impact over thoughts and prayers, prompts us all to carry her life’s work forward in providing material support to marginalized communities and fighting for a more just world.”

Despite recent statements of trans inclusion from Pope Francis, the Catholic Church has not historically been affirming of the LGBTQ+ Community. On December 10, 1988, ACT UP NY members alongside members of Women’s Health Action and Mobilization (WHAM!) disrupted a mass by Cardinal John O’Connor at St. Patricks Cathedral resulting in 111 arrests, 53 of whom were arrested inside the church, known as “Stop the Church”. This historic demonstration met two movements—one of which was protesting the O’Connor’s opposition of teaching safe sex practices in public schools and the general distribution of condoms, and the other being the Catholic church’s position on abortion rights.

“Cecilia’s immaculate work and the way she touched so many hearts and lives made her worthy of sainthood. Cecilia deserved this historic honor of the monumental funeral service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and to be cemented in history as a mother of multiple movements––of sex worker, immmigration, trans, and affirming healthcare movements,” said Oscar Diaz, Director of Communications at Trans Equity Consulting, and Gentili’s daughter. “Her wit, creativity, humor, and grace will be missed by the generations she mothered.”

During a time of increased anti-trans legislation and rhetoric across the country, Gentili receiving this outpouring of grief and celebration of her life signals her impact and the diginity of trans, immigrant, and sex worker lives writ-large. Her legacy of radical inclusion and revolutionary politics live on through her organization Trans Equity Consulting, as well as her namesake program C.O.I.N. at Callen-Lorde, which provides free healthcare for sex workers, and through the sustainable funding she secured for trans and sex worker communities in New York and beyond.

Gentili leaves behind immediate and chosen family, her partner Peter Scotto, her sister Ceyenne Doroshow, LaLa Zanell, Victoria Von Blaque, Cristina Herrera, and Tabytha Gonzalez, and her children, Rio Sofia, Cyd Nova, Maya Margarita, Katia Perea, Oscar Diaz, Qween Jean, Gia Love, Liaam Winslet, Chiquitita, Joshua Allen, Bianca Cerna, Gogo Graham, Amarilla Diosa, Mateo Belen, Krzysztof Pastuszka, and more. In remembrance of Cecilia’s work and legacy, the family has established a fund to support with funeral costs and to establish a donor advisory fund to continue her fight for trans liberation.

Gentili changed the material realities of countless queer and trans people, sex workers, and immigrants across the world. Access to hormones, bail money, immigration lawyers, surgeons, HIV meds, HASA vouchers, gender-affirming identification, and healthcare have been tenants of Cecilia’s organizing since she started in New York City.

Gentili’s impact:

- Gentili was instrumental in the development of two statewide bills to provide survivors of trafficking with record relief, and to end the criminalization of ‘loitering’ for the purpose of prostitution — the “Walking While Trans” Ban — a charge overwhelmingly leveled against transgender women, regardless of their involvement in the sex trade.

- She has a healthcare clinic at Callen Lorde named after her ongoing legacy of advocating for sex workers (COIN Clinic: Cecilia’s Occupational Inclusion Network)

- She’s raised over $15 million in city/state funding for the trans community and defended trans healthcare in the US. Supreme Court against Trump’s administration

- Her memoir, FALTAS, won the Stonewall Book Award and is set to be translated and published in Spanish by Editorial Caja Negra this year

- Her one-woman show RED INK had its off-Broadway debut last year to sold-out crowds and was picked up by Killer Films (May-December, Boy’s Don’t Cry) to be produced this year

- She spearheaded TRANSMISSION, NYC’s first trans music festival at Marsha P. Johnson State Park, and was a board member for Queer Art, Stonewall Foundation, and Alianza Trans Latinx

Related:

Notables

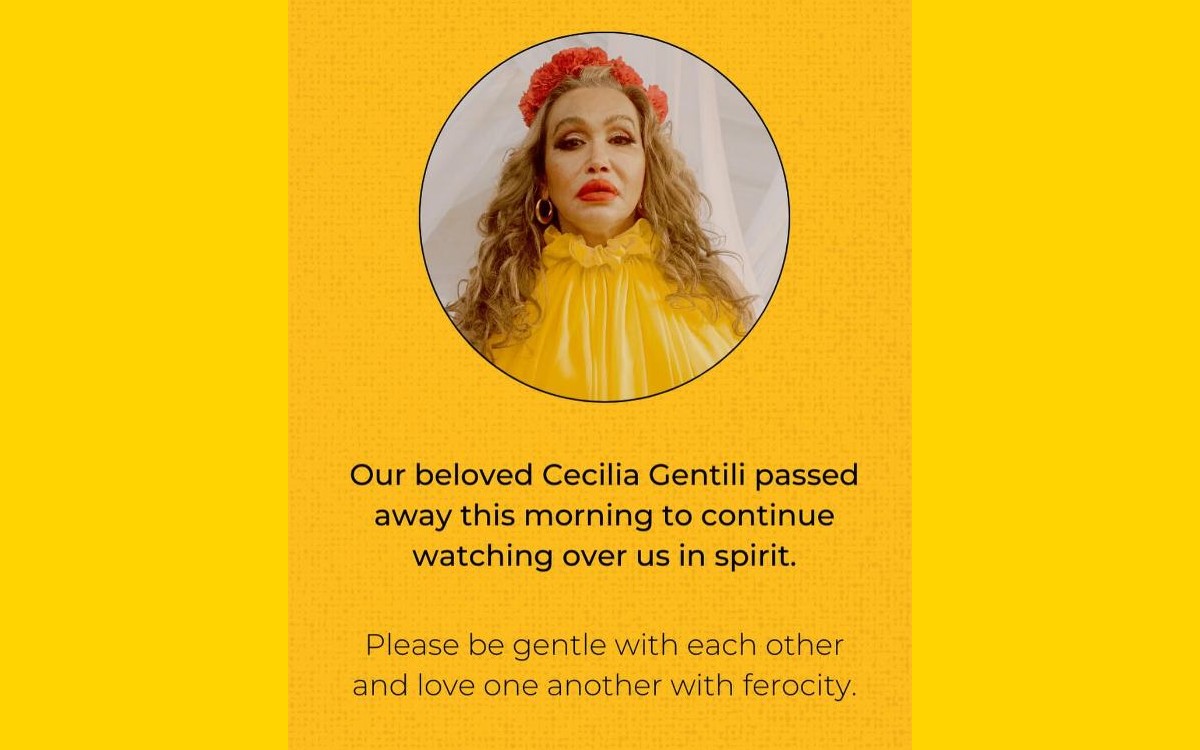

Cecilia Gentili, trans Latina activist, advocate & actress dies at 52

“In the art she created, in the stories shared, in the community uplifted, in the people served, her talent & love will never be forgotten”

NEW YORK – A towering presence in New York’s transgender community has died. In a post to her Instagram account on February 6, it was announced that the 52-year-old Argentina-born Cecilia Gentili had passed away.

“Our beloved Cecilia Gentili passed away this morning to continue watching over us in spirit,” the tribute read. “Please be gentle with each other and love one another with ferocity. We will be sharing more updates about services and what is to come in the following days. At this time, we’re asking for privacy, time, and space to grieve.”

An undocumented immigrant and then asylum seeker from Argentina, Gentili came to the United States pursuing a safer life to live authentically as a transgender woman. She lived undocumented for 10 years, hustling doing sex work which came with drug use. After surviving arrests and an immigration detention, she accessed recovery services and won asylum.

Among Gentili’s accomplishments was her work as a co-founder of her namesake COIN Clinic (Cecilia’s Occupational Inclusion Network ) at Callen-Lorde, a New York City-based leader in LGBTQ+ healthcare. She later was the managing director of policy for the world-renowned GMHC (originally the Gay Men’s Health Crisis).

With her background in the sex industry, she was a founding member of Decrim NY, a coalition working toward decriminalization, decarceration, and destigmatization of people in the sex trade. Gentili’s work focused on reducing coercion and promoting safety.

Decrim’s mission statement notes that decriminalization empowers sex workers to screen clients, negotiate condom use, and work collaboratively without the fear of criminalization, thereby reducing coercion and promoting safety.

She founded Trans Equity Consulting and collaborated with many major organizations on transgender and gender nonbinary rights. In addition to her advocacy and activist work, Gentili was an actress of note starring in the Netflix/FX hit series Pose as Ms. Orlando, the groundbreaking drama about the experiences of trans women of color set against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis in 1980s New York City.

GLAAD notes that Gentili’s memoir, Faltas, was published in late 2022 by Little Puss Press, Inc, and won an American Library Association’s 2023 Stonewall Book Award for nonfiction. Her one-woman show Red Ink was slated to make a comeback at the Public Theater this April.

Gentili was also a leading voice among the hundreds of New York Times contributors speaking out against the Times’ biased and inaccurate coverage of transgender people and their essential mainstream health care.

“Cecilia Gentili’s death is such a huge loss. She impacted so many, especially those in the trans community in New York City and beyond. This is the power of one person who used her identity and gifts to help more people be seen and heard. In the art she created, in the stories she shared, in the community she uplifted, in the people she served, Cecilia’s talent and love will never be forgotten,” GLAAD

GLAAD President and CEO Sarah Kate Ellis reacted to news of Gentili’s death posting to X/Twitter:

“Cecilia Gentili’s death is such a huge loss. She impacted so many, especially those in the trans community in New York City and beyond. This is the power of one person who used her identity and gifts to help more people be seen and heard. In the art she created, in the stories she shared, in the community she uplifted, in the people she served, Cecilia’s talent and love will never be forgotten.”

Chase Strangio, the Deputy Director for Transgender Justice with the ACLU National’s LGBT & HIV Project commented:

“15 years of deep trans love and storytelling. I am forever grateful. We grieved so many losses together. It feels impossible to grieve your loss. I will carry you always. I love you.”

New York Governor Kathy Hochul posted a picture of the two of them on Instagram and stated: “New York’s LGBTQ+ community has lost a champion in trans icon Cecilia Gentili. As an artist and steadfast activist in the trans rights movement, she helped countless people find love, joy, and acceptance. Our hearts are with her loved ones in this difficult time.”

Callen-Lorde released the following statement from CEO Patrick McGovern: “We are shocked and deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Cecilia Gentili. Cecilia was a fierce, fearless advocate and a leader, who spoke candidly about her own experiences as a trans woman of color. In doing so, she inspired countless others and truly paved the way for our communities — especially, sex workers and trans women of color — to access high quality and judgment free healthcare. Her legacy will live on through our work at Callen-Lorde and beyond.”

New York State Senator Brad Hoylman issued a statement describing the work and impact Cecilia Gentili delivered: “I’m devastated to learn of the passing of Cecilia Gentili, a pathbreaking civil rights activist, healthcare advocate, author and actress. I was honored to work with Cecilia on many issues in Albany as we passed legislation enshrining the civil rights protections for transgender New Yorkers into law, including the Gender Expression Nondiscrimination Act (GENDA), ending the so-called ban on “walking while trans,” eliminating the gay and trans panic defense in our criminal statutes, making New York a safe haven for transgender youth and their parents seeking gender-affirming care, and the creation of the New York State Lorena Borjas TGNB Wellness & Equity Fund. We could not have passed the multitude of bills improving the lives of transgender New Yorkers without her help and guidance. Cecilia was a force of nature who leaves a long trailblazing legacy behind. l will miss her deeply.”

Details of circumstances surrounding her death were unavailable and announcement of services will be shared at a later date according to the Instagram post.

-

Breaking News1 day ago

Breaking News1 day agoMajor victory for LGBTQ funding in LA County

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoKoaty & Sumner: Finding love in the adult industry

-

a&e features4 days ago

a&e features4 days agoLatina Turner comes to Bring It To Brunch

-

Books3 days ago

Books3 days agoTwo new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

-

Television5 days ago

Television5 days ago‘White Lotus,’ ‘Severance,’ ‘Andor’ lead Dorian TV Awards noms

-

Miscellaneous13 hours ago

Miscellaneous13 hours agoCan you really find true love in LA? Insights from a queer matchmaker

-

El Salvador2 days ago

El Salvador2 days agoLa marcha LGBTQ+ desafía el silencio en El Salvador

-

Arts & Entertainment13 hours ago

Arts & Entertainment13 hours agoIntuitive Shana gives us her hot take for July’s tarot reading