Movies

Outfest 2017 best of show

Jury and Audience award winners

David France (‘How to Survive a Plague’) probes the mysterious death of early LGBT activist Masha P. Johnson. (Photo by Amanda Rubin)

2017’s Outfest is now in the rearview mirror and the race is now on to find a way to capitalize on the show. Directors and producers, after being awarded, will continue on the film festival circuit and some will wide-release while others will continue looking for distribution deals.

But there were clearly some great competitors and entries.

After 11 hot and heady July days of premieres, parties, stars, screenings, talks, tears, laughter and applause, Outfest’s fantastic 35th anniversary edition is now a wrap. But if you missed any of the festival’s film highlights, never fear: Many of Outfest 2017’s top selections, including several of its Jury and Audience award winners, are coming back soon to theaters, TVs and monitors near you.

Here’s what to watch for, and when.

4 DAYS IN FRANCE (Jours de France)

Opens August 11, Ahrya Fine Arts

With Grindr as one of its main plot-drivers, this quirky French dramedy follows 30-something Pierre as he curiously leaves Paris to head into the countryside for a series of random social and sexual encounters, while his distraught partner Paul tries to track him via the gay dating app.

Opens August 25, theater(s) TBA

Writer-director Eliza Hittman took home the Outfest prize for Best Screenwriting in a U.S. Feature for this outer-edge-Brooklyn tale of 19-year-old Frankie (talented UK hottie Harris Dickinson), whose raging manlust is at odds with the working-class bro life he cultivates with his boardwalk-hanging buddies.

Prmeieres August 25, Showtime

This controversial documentary delves into some of the biggest behind-the-scenes rumors about Whitney Houston’s life, including her allegedly intimate relationship with long-time assistant Robyn Crawford, and attempts by the star and others to battle her addictions.

Opens September 8, Laemmle Royal

Outfest’s International Grand Jury Prize went to this powerful South African story of Xolani (out musician Nakhane Touré), who, during his annual pilgrimage to his rural tribal homeland to help initiate boys into manhood, has his deepest secret threatened by a rebellious young ward.

KEVYN AUCOIN: BEAUTY AND THE BEAST IN ME

Premieres September 14, Logo

Celebrity makeup artist Kevyn Aucoin is profiled in this biography that’s both fabulous and touching, largely made with footage Aucoin himself shot while making up some of the world’s top models and celebrities, including Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista, Cher, Janet Jackson, Liza Minnelli and Tina Turner.

Opens September 15, Monica Film Center

Winner of the Special Jury Award for Storytelling at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, this moving doc is trans filmmaker Yance Ford’s exploration of his brother’s murder on Long Island 25 years ago, and its permanent repercussions on his family.

CHAVELA trailer from Aubin Pictures on Vimeo.

Opens October 6, theater(s) TBA

Iconic Mexican singer Chavela Vargas is fondly remembered in this film — winner of Outfest’s Audience Award for Best Documentary — that traces her life as an unapologetically macho and woman-loving belter of poignant ranchera ballads who was nearly silenced at one point by her own hard-drinking ways, only to have a late-career rebirth of even greater international fame.

Opens October 27, theater(s) TBA

In this very male romance that’s been called “the British BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN,” young Yorkshire sheep farmer Johnny has resigned himself to a bleak and loveless life, until the arrival of studly Romanian migrant worker Gheorghe changes everything. The film won the World Cinema Directing Award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

THE DEATH AND LIFE OF MARSHA P. JOHNSON

Opens in October, exact dates & theater(s) TBA; later to Netflix

When the body of pioneering LGBTQ rights activist Marsha P. Johnson was found in the Hudson River in 1992, her death was deemed a suicide by the NYPD. This long overdue documentary, which picked up Outfest’s Programming Award for Freedom this year, traces Johnson’s courageous life, and reinvestigates the possible causes of her death.

Opens in November, exact dates & theater(s) TBA

This crowd-pleasing Outfest 2017 closing night film stars Alex Lawther (THE IMITATION GAME) as the unapologetically flamboyant Billy Bloom, who shakes things up at his conservative Florida school by running for homecoming queen. Bette Midler and Laverne Cox costar in the adaptation of a James St. James story.

Opens late 2017, dates & theater(s) TBA

The winner of Outfest’s Best US Narrative Feature Film prize this year is the lighthearted and tender story of somewhat-repressed thirty-something Chicagoan Zaynab, who falls for extroverted Mexican-American Alma, all the while discovering lucha libre wrestling as a release from the pressures of taking care of her Pakistan-born mother (played by Indian actress Shabana Azmi, who starred in the groundbreaking 1996 Indian lesbian-themed film FIRE).

Opens late 2017, dates & theater(s) TBA

Icelandic director Erlingur Thoroddsen won this year’s Programming Award for Artistic Achievement for his taut and beautiful thriller, in which Gunnar follows his ex-boyfriend Einar into Iceland’s rugged and haunting countryside, where, as they re-face the forces that drove them apart, someone or something is out to get them.

THE UNTOLD TALES OF ARMISTEAD MAUPIN

Opens late 2017, dates & theater(s) TBA

Director Jennifer M. Kroot (TO BE TAKEI) profiles author Armistead Maupin in this loving documentary, tracing his journey from Southern aristocrat to closeted conservative to chronicler of San Francisco gay culture, via his newspaper-serial-turned book-series Tales of the City.

I DREAM IN ANOTHER LANGUAGE (Sueño en otro idioma)

Opens late 2017, dates & theater(s) TBA

When a young university linguist travels to a small Mexican jungle town to save a dying language, he discovers that its last two native speakers haven’t spoken to each in decades — because, he finally realizes, they were once in love.

Movies

Moving doc ‘Come See Me’ is more than Oscar worthy

Poet Laureate Andrea Gibson, wife negotiate highs and lows of terminal illness

When Colorado Poet Laureate Andrea Gibson died from ovarian cancer in the summer of 2025, the news of their passing may have prompted an outpouring of grief from their thousands of followers on social media, but it was hardly a surprise.

That’s because Gibson – who had risen to both fame and acclaim in the early 2000s with intense live performances of their work that made them a “superstar” at Poetry Slam events – had been documenting their health journey on Instagram ever since receiving the diagnosis in 2021. During the process, they gained even more followers, who were drawn in by the reflections and explorations they shared in their daily posts. It was really a continuation, a natural evolution of their work, through which their personal life had always been laid bare, from the struggles with queer sexuality and gender they experienced in their youth to the messy relationships and painful breakups of their adult life; now, with precarious health prohibiting a return to the stage, they had found a new platform from which to express their inner experience, and their fans – not only the queer ones for whom their poetry and activism had become a touchstone, but the thousands more who came to know them through the deep shared humanity that exuded through their online presence – were there for it, every step of the way.

At the same time, and in that same spirit of sharing, there was another work in progress around Gibson: “Come See Me in the Good Light,” a film conceived by their friends Tig Notaro and Stef Willen and directed by seasoned documentarian Ryan White (“Ask Dr. Ruth”, “Good Night, Oppy”, “Pamela, a Love Story”), it was filmed throughout 2024, mostly at the Colorado home shared by Gibson and their wife, fellow poet Megan Falley, and debuted at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival before a release on Apple TV in November. Now, it’s nominated for an Academy Award.

Part life story, part career retrospective, and part chronicle of Gibson and Falley’s relationship as they negotiate the euphoric highs and heartbreaking lows of Gibson’s terminal illness together, it’s not a film to be approached without emotional courage; there’s a lot of pain to be vicariously endured, both emotional and physical, a lot of hopeful uplifts and a lot of crushing downfalls, a lot of spontaneous joy and a lot of sudden fear. There’s also a lot of love, which radiates not only from Gibson and Falley’s devotion and commitment to being there for each other, no matter what, but through the support and positivity they encounter from the extended community that surrounds them. From their circle of close friends, to the health care professionals that help them navigate the treatment and the difficult choices that go along with it, to the extended family represented by the community of fellow queer artists and poets who show up for Gibson when they make a triumphant return to the stage for a performance that everyone knows may well be their last, nobody treats this situation as a downer. Rather, it’s a cause to celebrate a remarkable life, to relish friendship and feelings, to simply be present and embrace the here and now together, as both witness and participant.

At the same time, White makes sure to use his film as a channel for Gibson’s artistry, expertly weaving a showcase for their poetic voice into the narrative of their survival. It becomes a vibrant testament to the raw power of their work, framing the poet as a seminal figure in a radical, feminist, genderqueer movement which gave voice to a generation seeking to break free from the constraints of a limited past and imagine a future beyond its boundaries. Even in a world where queer existence has become – yet again – increasingly perilous in the face of systemically-stoked bigotry and bullying, it’s a blend that stresses resilience and self-empowerment over tragedy and victimhood, and it’s more than enough to help us find the aforementioned emotional courage necessary to turn what is ultimately a meditation on dying into a validation of life.

That in itself is enough to make “Come See Me in the Good Light” worthy of Oscar gold, and more than enough to call it a significant piece of queer filmmaking – but there’s another level that distinguishes it even further.

In capturing Gibson and Falley as they face what most of us like to think of as an unimaginable future, White’s quietly profound movie puts its audience face-to-face with a situation that transcends all differences not only of sexuality or gender, but of race, age, or economic status as well. It confronts us with the inevitability few of us are willing to consider until we have to, the unhappy ending that is rendered certain by the joyful beginning, the inescapable conclusion that has the power to make the words “happily ever after” feel like a hollow promise. At the center of this loving portrait of a great American artist is a universal story of saying goodbye.

Yes, there is hope, and yes, good fortune often prevails – sometimes triumphantly – in the ongoing war against the cancer that has come to threaten the palpably genuine love this deeply-bonded couple has found together; but they (and we) know that, even in the best-case scenario, the end will surely come. All love stories, no matter how happy, are destined to end with loss and sorrow; it doesn’t matter that they are queer, or that their gender identities are not the same as ours – what this loving couple is going through, together, is a version of the same thing every loving couple lucky enough to hold each other for a lifetime must eventually face.

That they meet it head on, with such grace and mutual care, is the true gift of the movie.

Gibson lived long enough to see the film’s debut at Sundance, which adds a softening layer of comfort to the knowledge we have when watching it that they eventually lost the battle against their cancer; but even if they had not, what “Come See Me in the Good Light” shows us, and the unflinching candor with which it does so, delivers all the comfort we need.

Whether that’s enough to earn it an Oscar hardly matters, though considering the notable scarcity of queer and queer-themed movies in this year’s competition it might be our best shot at recognition.

Either way, it’s a moving and celebratory film statement with the power to connect us to our true humanity, and that speaks to a deeper experience of life than most movies will ever dare to do.

Movies

Radical reframing highlights the ‘Wuthering’ highs and lows of a classic

Emerald Fennell’s cinematic vision elicits strong reactions

If you’re a fan of “Wuthering Heights” — Emily Brontë’s oft-filmed 1847 novel about a doomed romance on the Yorkshire moors — it’s a given you’re going to have opinions about any new adaptation that comes along, but in the case of filmmaker Emerald Fennell’s new cinematic vision of this venerable classic, they’re probably going to be strong ones.

It’s nothing new, really. Brontë’s book has elicited controversy since its first publication, when it sparked outrage among Victorian readers over its tragic tale of thwarted lovers locked into an obsessive quest for revenge against each other, and has continued to shock generations of readers with its depictions of emotional cruelty and violent abuse, its dysfunctional relationships, and its grim portrait of a deeply-embedded class structure which perpetuates misery at every level of the social hierarchy.

It’s no wonder, then, that Fennell’s adaptation — a true “fangirl” appreciation project distinguished by the radical sensibilities which the third-time director brings to the mix — has become a flash point for social commentators whose main exposure to the tale has been flavored by decades of watered-down, romanticized “reinventions,” almost all of which omit large portions of the novel to selectively shape what’s left into a period tearjerker about star-crossed love, often distancing themselves from the raw emotional core of the story by adhering to generic tropes of “gothic romance” and rarely doing justice to the complexity of its characters — or, for that matter, its author’s deeper intentions.

Fennell’s version doesn’t exactly break that pattern; she, too, elides much of the novel’s sprawling plot to focus on the twisted entanglement between Catherine Earnshaw (Margot Robbie), daughter of the now-impoverished master of the titular estate (Martin Clunes), and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi), a lowborn child of unknown background origin that has been “adopted” by her father as a servant in the household. Both subjected to the whims of the elder Earnshaw’s violent temper, they form a bond of mutual support in childhood which evolves, as they come of age, into something more; yet regardless of her feelings for him, Cathy — whose future status and security are at risk — chooses to marry Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif), the financially secure new owner of a neighboring estate. Heathcliff, devastated by her betrayal, leaves for parts unknown, only to return a few years later with a mysteriously-obtained fortune. Imposing himself into Cathy’s comfortable-but-joyless matrimony, he rekindles their now-forbidden passion and they become entwined in a torrid affair — even as he openly courts Linton’s naive ward Isabella (Alison Oliver) and plots to destroy the entire household from within. One might almost say that these two are the poster couple for the phrase “it’s complicated.” and it’s probably needless to say things don’t go well for anybody involved.

While there is more than enough material in “Wuthering Heights” that might easily be labeled as “problematic” in our contemporary judgments — like the fact that it’s a love story between two childhood friends, essentially raised as siblings, which becomes codependent and poisons every other relationship in their lives — the controversy over Fennell’s version has coalesced less around the content than her casting choices. When the project was announced, she drew criticism over the decision to cast Robbie (who also produced the film) opposite the younger Elordi. In the end, the casting works — though the age gap might be mildly distracting for some, both actors deliver superb performances, and the chemistry they exude soon renders it irrelevant.

Another controversy, however, is less easily dispelled. Though we never learn his true ethnic background, Brontë’s original text describes Heathcliff as having the appearance of “a dark-skinned gipsy” with “black fire” in his eyes; the character has typically been played by distinctly “Anglo” men, and consequently, many modern observers have expressed disappointment (and in some cases, full-blown outrage) over Fennel’s choice to use Elordi instead of putting an actor of color for the part, especially given the contemporary filter which she clearly chose for her interpretation for the novel.

In fact, it’s that modernized perspective — a view of history informed by social criticism, economic politics, feminist insight, and a sexual candor that would have shocked the prim Victorian readers of Brontë’s novel — that turns Fennell’s visually striking adaptation into more than just a comfortably romanticized period costume drama. From her very opening scene — a public hanging in the village where the death throes of the dangling body elicit lurid glee from the eagerly-gathered crowd — she makes it oppressively clear that the 18th-century was not a pleasant time to live; the brutality of the era is a primal force in her vision of the story, from the harrowing abuse that forges its lovers’ codependent bond, to the rigidly maintained class structure that compels even those in the higher echelons — especially women — into a kind of slavery to the system, to the inequities that fuel disloyalty among the vulnerable simply to preserve their own tenuous place in the hierarchy. It’s a battle for survival, if not of the fittest then of the most ruthless.

At the same time, she applies a distinctly 21st-century attitude of “sex-positivity” to evoke the appeal of carnality, not just for its own sake but as a taste of freedom; she even uses it to reframe Heathcliff’s cruel torment of Isabella by implying a consensual dom/sub relationship between them, offering a fragment of agency to a character typically relegated to the role of victim. Most crucially, of course, it permits Fennell to openly depict the sexuality of Cathy and Heathcliff as an experience of transgressive joy — albeit a tormented one — made perhaps even more irresistible (for them and for us) by the sense of rebellion that comes along with it.

Finally, while this “Wuthering Heights” may not have been the one to finally allow Heathcliff’s ambiguous racial identity to come to the forefront, Fennell does employ some “color-blind” casting — Latif is mixed-race (white and Pakistani) and Hong Chau, understated but profound in the crucial role of Nelly, Cathy’s longtime “paid companion,” is of Vietnamese descent — to illuminate the added pressures of being an “other” in a world weighted in favor of sameness.

Does all this contemporary hindsight into the fabric of Brontë’s epic novel make for a quintessential “Wuthering Heights?” Even allowing that such a thing were possible, probably not. While it presents a stylishly crafted and thrillingly cinematic take on this complex classic, richly enhanced by a superb and adventurous cast, it’s not likely to satisfy anyone looking for a faithful rendition, nor does it reveal a new angle from which the “romance” at its center looks anything other than toxic — indeed, it almost fetishizes the dysfunction. Even without the thorny debate around Heathcliff’s racial identity, there’s plenty here to prompt purists and revisionists alike to find fault with Fennell’s approach.

Yet for those looking for a new window into to this perennial classic, and who are comfortable with the radical flourish for which Fennell is already known, it’s an engrossing and intellectually stimulating exploration of this iconic story in a way that exchanges comfortable familiarity for unpredictable chaos — and for cinema fans, that’s more than enough reason to give “Wuthering Heights” a chance.

Movies

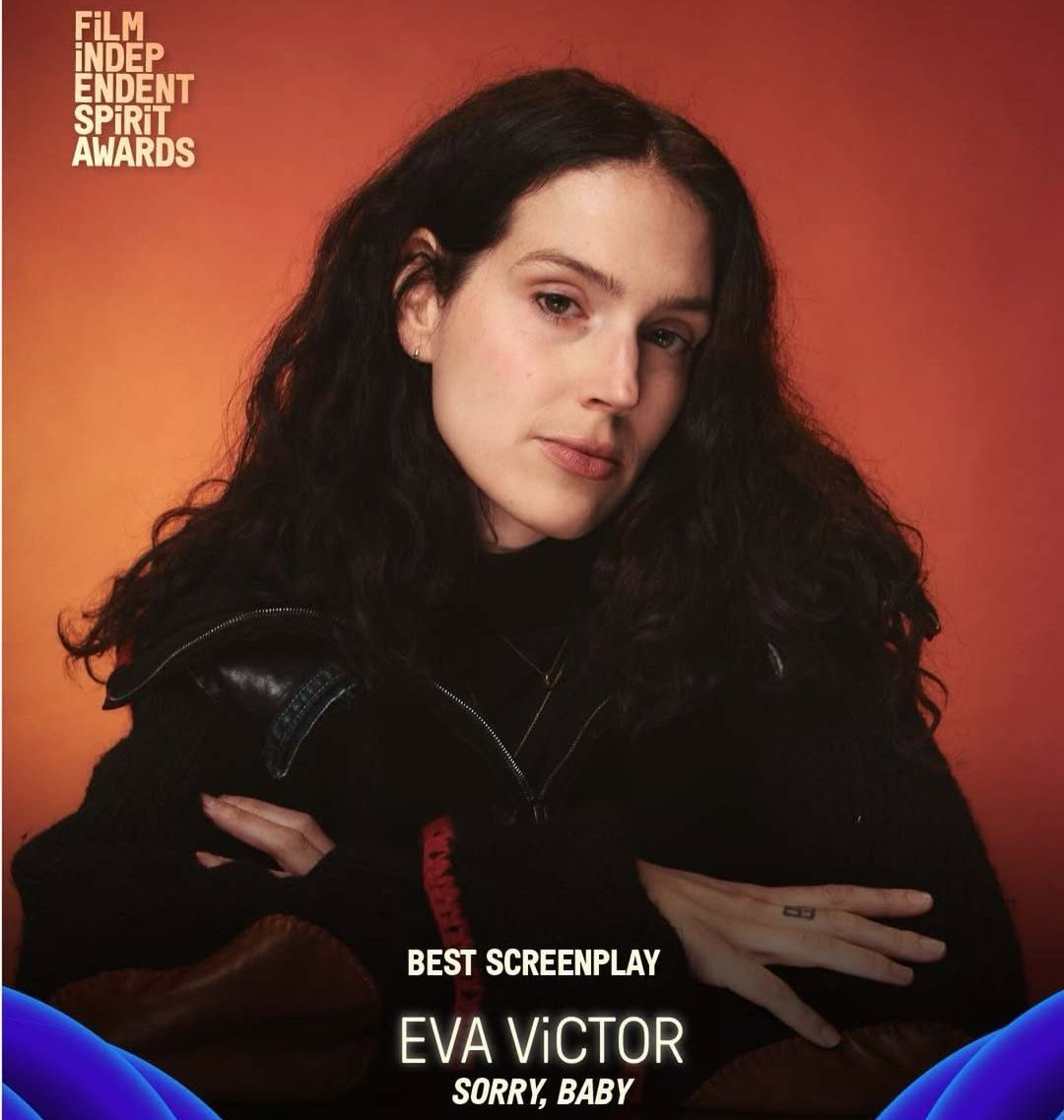

Eva Victor winning best screenplay, Erin Doherty winning supporting actress, and more queer highlights of the 2026 Film Independent Spirit Awards

‘Sorry, Baby’ and ‘Lurker’ were among the big winners

Sorry, Baby, Train Dreams, and Lurker were the big winners of this year’s Film Independent Spirit Awards.

The Spirit Awards were held Sunday, Feb. 15, at the Hollywood Palladium in Los Angeles, California, with stars Eva Victor, Rose Byrne, Keke Palmer, Tessa Thompson, Amy Madigan, Erin Doherty, and Dylan O’Brien in attendance.

Train Dreams won best feature and best director, Victor won the best screenplay prize for Sorry, Baby. Pee-wee as Himself won the award for best new non-scripted or documentary series, and Doherty continued her awards season sweep for Adolescence with a win for best supporting performance in a new scripted series.

While accepting an award for writing Sorry, Baby, Victor said: “Making this film independently is the only way I could have ever made it the way I wanted to. I’m so, so grateful for independent cinema, and I love everyone here for that.”

Where the Oscars largely ignored the best queer indie hits, the Spirit Awards became this year’s go-to awards show for under-the-radar favorites. Sorry, Baby, Twinless, Peter Hujar’s Day, and Lurker all scored best feature nominations, while Ira Sachs (you can read The Blade’s interview here) was nominated for best director. Notably, all four of those films premiered at Sundance.

In the lead performance film category, Tessa Thompson (you can read The Blade’s interview here), Ben Whishaw, Théodore Pellerin, and Dylan O’Brien were all nominated, while Oscar nominee Rose Byrne took home the top honor. Twinless may have gone home empty-handed, but the film was a huge point of conversation throughout the award ceremony.

Beyond the films they recognize, what makes the Spirit Awards different from more mainstream award shows is the lack of gender specific categories; the Oscars traditionally have separate categories for male and female performers.

The Gotham Awards went gender-neutral in 2021, and the Spirit Awards followed during its 2023 ceremony. “We think the ways we’ve created equity through our award show is not only a reflection of the world we live in, but representative of the industry and what we want it to look like,” Film Independent acting president Brenda Robinson told me in an interview for Variety in May 2025.

Movies

50 years later, it’s still worth a return trip to ‘Grey Gardens’

Documentary remains entertaining despite its darkness

If we were forced to declare why “Grey Gardens” became a cult classic among gay men, it would be all the juicy quotes that have become part of the queer lexicon.

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of its theatrical release this month, the landmark documentary profiles two eccentrics: Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale and her daughter, Edith Bouvier Beale (known as “Big” and “Little” Edie, respectively), the aunt and cousin of former first lady Jaqueline Kennedy Onassis and socialite Lee Radziwell. Once moving within an elite circle of American aristocrats, they had fallen into poverty and were living in isolation at their run-down estate (the Grey Gardens of the title) in East Hampton, Long Island; they re-entered the public eye in 1972 after local authorities threatened eviction and demolition of their mansion over health code violations, prompting their famous relatives to swoop in and pay for the necessary repairs to avoid further family scandal.

At the time, Radziwell had enlisted filmmaking brothers David and Albert Maysles to take footage for a later-abandoned project of her own, bringing them along when she went to put in an appearance at the Grey Gardens clean-up efforts. It was their first encounter with the Beales; the second came two years later, when they returned with their cameras (but without Radziwell) and proceeded to make documentary history, turning the two Edies into unlikely cultural icons in the process.

On paper, it reads like something painful: two embittered former socialites, a mother and daughter living among a legion of cats and raccoons in the literal ruins of their former life, where they dwell on old memories, rehash old conflicts, and take out their resentments on each other, attempting to keep up appearances while surviving on a diet that may or may not include cat food. Truthfully, it is sometimes difficult to watch, which is why it’s easier to approach from surface level, focusing on the “wacky” eccentricities and seeing the Beales as objects for ridicule.

Yet to do so is to miss the true brilliance of a movie that is irresistible, unforgettable, and fascinating to the point of being hypnotic, and that’s because of the Beales themselves, who are far too richly human to be dismissed on the basis of conventional judgments.

First is Little Edie, in her endless array of headscarves (to cover her hair loss from alopecia) and her ever-changing wardrobe of DIY “revolutionary costumes,” a one-time model and might-have-been showgirl who is obviously thrilled at having an audience and rises giddily to the occasion like a pro. Flamboyant, candid, and smarter than we think, she’s also fearlessly vulnerable; she gives us access to an emotional landscape shaped by the heartbreaks of a past that’s gradually revealed as the movie goes on, and it’s her ability to pull herself together and come back fighting that wins us over. By the time she launches into her monologue about being a “S-T-A-U-N-C-H” woman, we have no doubt that it’s true.

Then there’s Big Edie, who comes across as an odd mix of imperious dowager and down-to-earth grandma. She gets her own chance to shine for the camera, especially in the scenes where she reminisces about her early days as a “successful” amateur vocalist, singing along to records of songs she used to perform as glimpses emerge of the beauty and talent she commanded in her prime. She’s more than capable of taking on her daughter in their endless squabbles, and savvy enough to score serious points in the conflict, like stirring up jealousy with her attentions to beefy young handyman Jerry – whom the younger Edie has dubbed “the Marble Faun” – when he comes around to share a feast of boiled corn-on-the-cob with them. “Jerry likes the way I do my corn,” she deadpans to the camera, even though we know it’s meant for Little Edie.

It’s not just that their eccentricities verge on camp; that’s certainly an undeniable part of the appeal, but it falls away quickly as you begin to recognize that even if these women are putting on a show for the camera, they’re still being completely themselves – and they are spectacular.

Yes, their verbal sparring is often shrill and palpably toxic – in particular, Big Edie has no qualms about belittling and shaming her daughter in an obviously calculated effort to undermine her self-esteem and discourage her from making good on her repeated threats to leave Grey Gardens. We know she is acting from fear of abandonment, but it’s cruel, all the same.

These are the moments that disturb us more than any of the dereliction we see in their physical existence; fed by nostalgia and forged in a deep codependence that neither wants to acknowledge, their dynamic reflects years of social isolation that has made them into living ghosts, going through the habitual motions of a long-lost life, ruminating on ancient resentments, and mulling endlessly over memories of the things that led them to their outcast state. As Little Edie says early on, “It’s very difficult to keep the line between the past and the present. Do you know what I mean?”

That pithy observation, spoken conspiratorially to the Maysles’ camera, sets the tone for the entirety of “Grey Gardens,” perhaps even suggesting an appropriate point of meditation through which to contemplate everything that follows. It’s a prime example of the quotability that has helped this odd little movie endure as a fixture in queer culture; for many LGBTQ people, both Edies – born headstrong, ambitious, and independent into a social strata that only wanted its women to be well-behaved – became touchstones of frustrated longing, of living out one’s own fabulousness in isolated secrecy. Add to that shared inner experience Little Edie’s knack for turning scraps into kitschy fashion (and the goofy-but-joyous flag dance she performs as a sort of climactic topper near the end), and it should be obvious why the Maysles Brothers’ little project still resonates with the community five decades later.

Indeed, watching it in today’s cultural climate, it strikes chords that resonate through an even wider spectrum, touching on feminist themes through these two “problematic” women who have been effectively banished for refusing to fit into a mold, and on the larger issue of social and economic inequality that keeps them trapped, ultimately turning them against each other in their powerlessness.

With that in mind, it’s clear these women were never filmed to be objects of ridicule. They’re survivors in a world in which even their unimaginably wealthy relatives would rather look away, offering a bare minimum of help only when their plight becomes a matter of public family embarrassment, and the resilience they show in the face of tremendous adversity makes them worthy of celebration, instead.

That’s why “Grey Gardens” still hits close to home, why it entertains despite its darkness, and why we remember it as something bittersweet but beautiful. By the end of it, we recognize that the two Edies could be any of us, which means they are ALL of us – and if they can face their challenges with that much “revolutionary” spirit, then maybe we can be “staunch” against our adversities, too.

Movies

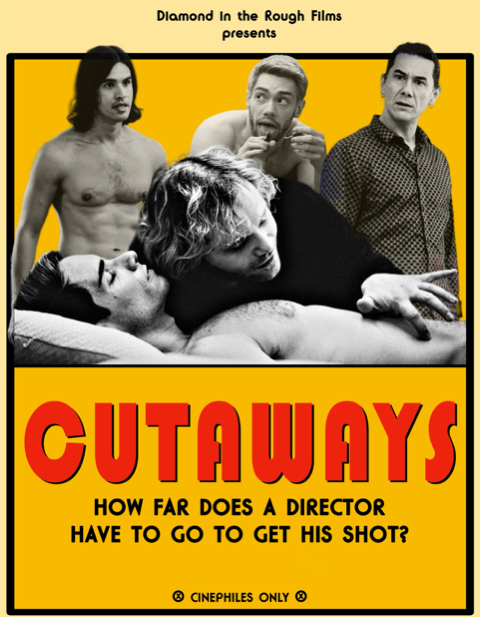

‘Cutaways’ and the risk queer cinema forgot

Mark Schwab’s newest film confronts a contemporary problem in queer media: commercialization, tokenization, and a growing aversion to risk.

There is nothing radical about a queer film that plays it safe. From the fabulous shock and awe of John Waters’ obscene ethos, to the formal ruptures of New Queer Cinema in the work of Gregg Araki and Todd Haynes, to Bruce LaBruce’s incendiary provocations, LGBTQ+ filmmakers have historically carved out spaces by breaking rules. Queer cinema was staged in resistance, unsettling viewers and insisting that queer life could not be easily palatable to the masses.

Yet, that history has grown increasingly distant in a media landscape dominated by the repetitive narrative templates, endlessly repackaged and sold as “representation.” In this moment, Cutaways, the latest film from Mark Schwab, arrives as a refreshing (and unsettling) intervention. Cutaways premieres February 3rd on Amazon Prime and Vimeo on Demand.

The dark, intermittently comical film screened at the 2025 SF Queer Film Festival, but its run through the LGBTQ+ festival circuit was brief. Schwab tells the Blade, “It screened at the 2025 SF Queer Film Festival, but it was rejected by every other LGBTQ film festival I entered it into.” What he heard in response wasn’t that the film lacked quality or creative direction. “They love the film,” he explains, “but they were too afraid to program in this climate.”

The hesitation speaks less to Cutaways as an artistic project than to a broader resistance to risk in queer media. Schwab, who grew up watching queer films that transgressed conventional norms, finds the shift troubling. “I grew up with Gregg Araki, and John Waters, and Bruce LaBruce, and Todd Haynes’ Poison,” he eagerly explains, “Those were the films that I admired as a young gay boy… And now it seems like the LGBTQ community just wants everything to be a Lifetime movie, and that’s fine – but does it have to only be that?”

Cutaways refuses to play it safe, rejecting the familiar mise-en-scène that increasingly defines contemporary queer cinema. Set entirely within a Downtown Los Angeles artist space staged as an adult film set, the film follows Evan Quick, a once-respected filmmaker whose career crashes and burns after public backlash. Desperate to keep working, Evan accepts a job directing pornography, a choice that quickly sheds any comic veneer and settles into something more existential. What could have been framed as sexual provocation is deliberately restrained, trading spectacle for unease.

Schwab is clear that the adult film setting is not about provocation. “I knew I wanted to use a porn set as an arena,” he explains, “I’m not judging porn here at all.” Instead, Schwab frames the film in terms of questions that the audience considers while watching: “How did these characters get there? And what are they doing there? And how are they dealing with their issues within that world?”

That sense of entrapment – characters forced to confront themselves without escape – has long fascinated Schwab. One film that was particularly powerful for him was The Boys in the Band (1970), serving as a formative influence. “Watching these characters have to deal with each other’s relationships and issues … and they’re trapped in that party… I love that.” In Cutaways, no one can walk away. Everyone is there for a reason – a reason that audiences must figure out for themselves.

Watching Cutaways, it’s easy to read its characters through the familiar lens of victimhood. Schwab, however, resists that framing entirely. “All the characters want to be there,” he says, “It’s almost like there are no victims in the movie … They’re all exercising their own power in their own way.”

That philosophy extends to the film’s central figure, Evan Quick. Schwab isn’t interested in writing characters to be likable or unlikable so much as depicting them for who they are. “I don’t feel sympathetic to Evan, but I do feel empathetic,” he says. Evan stages a question that sits uncomfortably close to creative individuals: What happens when the work that defines you is suddenly at risk? Or as Schwab puts it: “How far is he willing to go to follow his passion?”

Despite the film’s thematic weight, Schwab rejects the notion that Cutaways is delivering a lesson. “None of my films ever have a message … They are stories,” he tells the Blade. Instead of preaching a message, Schwab’s films insist on attention to detail: “My films are no good if you’re gonna be looking at your phone at the same time … You have to pay attention … You’re just gonna miss way too much.”

Cutaways sits at an uneasy intersection between those invested in preserving the commercialized norms and a queer cinematic legacy defined by risk. That friction may explain its reception, but it also marks the film’s necessity. In an era dominated by repeatable formats and tokenized representation, Schwab’s film insists on uneasiness, ambiguity, and a love for the unpredictable.

Queer cinema must be defined by urging the audience to sit and watch – even when it’s uncomfortable. Cutaways doesn’t just recall that tradition. It reminds us why it mattered in the first place.

Movies

Van Sant returns with gripping ‘Dead Man’s Wire’

Revisiting 63-hour hostage crisis that pits ethics vs. corporate profits

In 1976, a movie called “Network” electrified American moviegoers with a story in which a respected news anchor goes on the air and exhorts his viewers to go to their windows and yell, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!”

It’s still an iconic line, and it briefly became a familiar catch phrase in the mid-’70s lexicon of pop culture, the perfect mantra for a country worn out and jaded by a decade of civil unrest, government corruption, and the increasingly powerful corporations that were gradually extending their influence into nearly all aspects of American life. Indeed, the movie itself is an expression of that same frustration, a satire in which a man’s on-the-air mental health crisis is exploited by his corporate employers for the sake of his skyrocketing ratings – and spawns a wave of “reality” programming that sensationalizes outrage, politics, and even violence to turn it into popular entertainment for the masses. Sound familiar?

It felt like an exaggeration at the time, an absurd scenario satirizing the “anything-for-ratings” mentality that had become a talking point in the public conversation. Decades later, it’s recognized as a savvy premonition of things to come.

This, of course, is not a review of “Network.” Rather, it’s a review of the latest movie by “new queer cinema” pioneer Gus Van Sant (his first since 2018), which is a fictionalized account of a real-life on-the-air incident that happened only a few months after “Network” prompted national debate about the media’s responsibility in choosing what it should and should not broadcast – and the fact that it strikes a resonant chord for us in 2026 makes it clear that debate is as relevant as ever.

“Dead Man’s Wire” follows the events of a 63-hour hostage situation in Indianapolis that begins when Tony Kiritsis (Bill Skarsgård) shows up for an early morning appointment at the office of a mortgage company to which he is under crippling debt. Ushered into a private office for a one-on-one meeting with Dick Hall (Dacre Montgomery), son of the brokerage’s wealthy owner, he kidnaps the surprised executive at gunpoint and rigs him with a “dead man’s wire” – a device that secures a shotgun against a captive’s head that is triggered to discharge with any attempt at escape – before calling the police himself to issue demands for the release of his hostage, which include immunity for his actions, forgiveness of his debt, reimbursement for money he claims was swindled from him by the company, and an apology.

The crisis becomes a public spectacle when Kiritsis subjects his prisoner to a harrowing trip through the streets back to his apartment, which he claims is wired with explosives. As the hours tick by, the neighborhood surrounding his building becomes a media circus. Realizing that law enforcement officials are only pretending to negotiate while they make plans to take him down, he enlists the aid of popular local radio DJ Fred Heckman (Colman Domingo) to turn the situation into a platform for airing his grievances – and for calling out the predatory financial practices that drove him to this desperate situation in the first place.

We won’t tell you how it plays out, for the sake of avoiding spoilers, even though it’s all a matter of public record. Suffice to say that the crisis reaches a volatile climax in a live broadcast that’s literally one wrong move away from putting an explosion of unpredictable real-life violence in front of millions of TV viewers.

In 1977, the Kiritsis incident certainly contributed to ongoing concerns about violence on television, but there was another aspect of the case that grabbed public attention: Kiritsis himself. Described by those who knew him as “helpful,” “kind,” and a “hard worker,” he was hardly the image of a hardened criminal, and many Americans – who shared his anger and desperation over the opportunistic greed of a finance industry they believed was playing them for profit – could sympathize with his motives. Inevitably, he became something of a populist hero – or anti-hero, at least – for standing up to a stacked system, an underdog who spoke things many of them felt and took actions many of them wished they could take, too.

That’s the thing that makes this true-life crime adventure uniquely suited to the talents of Van Sant, a veteran indie auteur whose films have always specialized in humanizing “outsider” characters, usually pushed to the fringes of society by circumstances only partly under their own control, and often driven to desperate acts in pursuit of an unattainable dream. Tony Kiritsis, a not-so-regular “Joe” whose fumbling efforts toward financial security have been turned against him and who seeks only recompense for his losses, fits that profile to a tee, and the filmmaker gives us a version of him (aided by Skarsgård’s masterfully modulated performance) which leaves little doubt that he – from a certain point of view, at least – is the story’s unequivocal protagonist, no matter how “lawless” his actions might be.

It helps that the film gives us much more exposure to Kiritsis’ personality than could be drawn merely from the historic live broadcast that made him infamous, spending much of the movie focused on his interactions with Hall (performed with equally well-managed nuance by Montgomery) during the two days spent in the apartment, as well as his dealings with DJ Heckman (rendered with street savvy and close-to-the-chest cageyness by Domingo); for balance, we also get fly-on-the-wall access to the interplay outside between law enforcement officials (including Cary Elwes’ blue collar neighborhood cop) as they try to navigate a potentially deadly situation, and to the jockeying of an ambitious rookie street reporter (Myha’la) with the rest of the press for “scoops” with each new development.

But perhaps the interaction that finally sways us in Kiritsis’s favor takes place via phone with his captive’s mortgage tycoon father (Al Pacino, evoking every unscrupulous, amoral mob boss he’s ever played), who is willing to sacrifice his own son’s life rather than negotiate a deal. It’s a nugget of revealed avarice that was absent in the “official” coverage of the ordeal, which largely framed Kiritsis as mentally unstable and therefore implied a lack of credibility to his accusations against Meridian Mortgage. It’s also a moment that hits hard in an era when the selfishness of wealthy men feels like a particularly sore spot for so many struggling underdogs.

That’s not to say there’s an overriding political agenda to “Dead Man’s Wire,” though Van Sant’s character-driven emphasis helps make it into something more than just another tension-fueled crime story; it also works to raise the stakes by populating the story with real people instead of predictable tropes, which, coupled with cinematographer Arnaud Potier’s studied emulation of gritty ‘70s cinema and the director’s knack for inventive visual storytelling, results in a solid, intelligent, and darkly humorous thriller – and if it reconnects us to the “mad-as-hell” outrage of the “Network” era, so much the better.

After all, if the last 50 years have taught us anything about the battle between ethics and profit, it’s that profit usually wins.

Movies

‘Becoming a Man in 127 EASY Steps’ changes the narrative when it comes to LGBTQ storytelling

Trans filmmaker and performer Scott Schofield dazzles in this one-person special, raising the bar when it comes to telling our stories

There is a sameness to filmed solo performances: a performer with a microphone, a minimalist backdrop, and a linear delivery. Designed more for economic efficiency than emotional expression, the form works, but it rarely surprises.

“This is gonna be a little…different,” Emmy-nominated actor/writer/producer Scott Turner Schofield declares at the top of his new one-hour special, Becoming a Man in 127 EASY Steps. It’s now streaming on Kinema.

Co-Directors Andrea James and Puppett adapted Schofield’s long-running live performance into a work that understands structure as art. Built around 127 discrete stories — originally selected live and never told in the same order twice — the film resists linear autobiography. Each story stands alone; they arrive out of order, sometimes raw and live, sometimes boldly cinematic; and no one story is positioned as definitive. That structure is the thesis: identity is not linear, nobody is just one thing.

What happens after transition has never been very interesting to mass media — is it because that would be too human? Rather than staying stuck in the amber of the moment of transition, this film invites you to sit with a person who has lived far into a future most trans people can’t imagine. It’s a detailed, balanced portrait, with humor sharp enough to puncture reverence and tenderness strong enough to survive it.

The approach places Becoming a Man in 127 EASY Steps in a lineage closer to Jon Leguizamo’s solo works than to a Netflix stand-up special. Like Leguizamo’s best pieces, Schofield’s film uses performance as a vehicle for history, embodiment, and cultural critique, expanding the language of solo storytelling rather than flattening it for easy consumption.

Speaking of Leguizamo, as an actor, Schofield moves effortlessly through humor, absurdity, grief, tenderness, and philosophical reflection, but the delivery remains grounded. His charm is indelible and irresistibly watchable.

Literate without being precious, Schofield’s writing lands its insights through specificity rather than thesis statements. The funniest moments aren’t jokes about gender; they’re observations about being alive, from an off-the-wall perspective. A vegetarian lasagna recipe doubles as a guide to emotional readiness; a Croatian skinny-dipping misadventure becomes accidental “feminist fieldwork.”

One line, recalling a formative childhood memory, crystallizes the film’s emotional intelligence: “Uncle Bill’s death gave me one free day of childhood,” Schofield exclaims, recalling the first time he got to wear boys’ underwear underneath borrowed clothes after an unexpected tragedy. “One day, when I knew that, no matter what I looked like on the outside, I was who I was supposed to be underneath.” The audience bursts into laughter, but that sentence dismantles half the culture war arguments about gender. Soundbites like these are an enjoyable refrain throughout the hour-long film.

Allen Martsch’s animation in “Step 127” lifts the piece to another level. Swirling in images that harken back to Hedwig and the Angry Inch’s touching but somehow spiritual illustrations, Schofield refuses both the Hero Myth and the Everyman narrative: “I can’t identify with either one of those men. Neither one feels quite right.” Instead, the piece insists on process, on what it means to keep becoming without knowing the ending — turning page after page.

There is rage here, and grief, and of course it is intensely political — even more so, at this moment in history. But those emotions arrive through specificity rather than slogans. When Schofield says, “It’s not death I want. It’s change,” he’s naming a fact most trans people recognize, whether they admit it or not.

Trans man leads remain exceedingly rare in narrative cinema. Films like Close to You, starring Eliot Page, mark important progress by placing a trans man at the emotional center of a fictional story. Becoming a Man in 127 EASY Steps offers transmasculine interiority in a different register — non-fictional and self-authored — pushing representation forward in another crucial way.

The film’s existence is itself a low-key indictment of the industry in which trans actors remain marginalized. Becoming a Man in 127 EASY Steps’s production budget was crowdfunded, listing 378 community supporters in its credits. Any critique of the film is due to its lack of resources: it needs a better sound mix, two balconies of audience for the introductory monologue, and a slicker presentation overall. One can’t help but ask: what could this have been with the resources routinely afforded to far less ambitious (straight, cisgender) solo projects?

The answer feels obvious. This is an HBO special in every way but platform. It is expansive in form, rigorous in thought, and generous with its audience. It does what the best solo performance films do, using one body to tell a much larger story, without simplifying it. The question is not whether the film belongs on a larger platform. It plainly does. The question is: why isn’t it already there?

It arrives instead on Kinema, an emerging streaming platform built to support independent film through live and virtual screenings, community engagement, and social justice fundraising.

Becoming a Man in 127 EASY Steps deserves to be seen, not as a niche artifact, but as a benchmark for what filmed performance can be. It deserves the scale, seriousness, and cultural placement that straight cisgender solo works enjoy.

Instead, it arrives carried by community, and quietly raises the bar for what filmed performance can be.

Watch Becoming a Man in 127 EASY Steps now on Kinema. Find out more at 127steps.com.

Review provided by Valentin Arnold, guest to the Blade

Movies

A ‘Battle’ we can’t avoid

Critical darling is part action thriller, part political allegory, part satire

When Paul Thomas Anderson’s “One Battle After Another” debuted on American movie screens last September, it had a lot of things going for it: an acclaimed Hollywood auteur working with a cast that included three Oscar-winning actors, on an ambitious blockbuster with his biggest budget to date, and a $70 million advertising campaign to draw in the crowds. It was even released in IMAX.

It was still a box office disappointment, failing to achieve its “break-even” threshold before making the jump from big screen to small via VOD rentals and streaming on HBO Max. Whatever the reason – an ambivalence toward its stars, a lack of clarity around what it was about, divisive pushback from both progressive and conservative camps over perceived messaging, or a general sense of fatigue over real-world events that had pushed potential moviegoers to their saturation point for politically charged material – audiences failed to show up for it.

The story did not end there, of course; most critics, unconcerned with box office receipts, embraced Anderson’s grand-scale opus, and it’s now a top contender in this year’s awards race, already securing top prizes at the Golden Globe and Critics’ Choice Awards, nominated for a record number of SAG’s Actor Awards, and almost certain to be a front runner in multiple categories at the Academy Awards on March 15.

For cinema buffs who care about such things, that means the time has come: get over all those misgivings and hesitations, whatever reasons might be behind them, and see for yourself why it’s at the top of so many “Best Of” lists.

Adapted by Anderson from the 1990 Thomas Pynchon novel “Vineland,” “One Battle” is part action thriller, part political allegory, part jet-black satire, and – as the first feature film shot primarily in the “VistaVision” format since the early 1960s – all gloriously cinematic. It unspools a near-mythic saga of oppression, resistance, and family bonds, set in an authoritarian America of unspecified date, in which a former revolutionary (Leonardo DiCaprio) is attempting to raise his teenage daughter (Chase Infiniti) under the radar after her mother (Teyana Taylor) betrayed the movement and fled the country. Now living under a fake identity and consumed by paranoia and a weed habit, he has grown soft and unprepared when a corrupt military officer (Sean Penn) – who may be his daughter’s real biological father – tracks them down and apprehends her. Determined to rescue her, he reconnects with his old revolutionary network and enlists the aid of her karate teacher (Benicio Del Toro), embarking on a desperate rescue mission while her captor plots to erase all traces of his former “indiscretion” with her mother.

It’s a plot straight out of a mainstream action melodrama, top-heavy with opportunities for old-school action, sensationalistic violence, and epic car chases (all of which it delivers), but in the hands of Anderson – whose sensibilities always strike a provocative balance between introspection, nostalgia, and a sense of apt-but-irreverent destiny – it becomes much more intriguing than the generic tropes with which he invokes to cover his own absurdist leanings.

Indeed, it’s that absurdity which infuses “One Battle” with a bemusedly observational tone and emerges to distinguish it from the “action movie” format it uses to relay its narrative. From DiCaprio (whose performance highlights his subtle comedic gifts as much as his “serious” acting chops) as a bathrobe-clad underdog hero with shades of The Dude from the Coen Brothers’ “The Big Liebowski,” to the uncomfortably hilarious creepy secret society of financially elite white supremacists that lurks in the margins of the action, Anderson gives us plenty of satirical fodder to chuckle about, even if we cringe as we do it; like that masterpiece of too-close-to-home political comedy, Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 nuclear holocaust farce “Dr. Strangelove,” it offers us ridiculousness and buffoonery which rings so perfectly true in a terrifying reality that we can’t really laugh at it.

That, perhaps, is why Anderson’s film has had a hard time drawing viewers; though it’s based on a book from nearly four decades ago and it was conceived, written, and created well before our current political reality, the world it creates hits a little too close to home. It imagines a roughly contemporary America ruled by a draconian regime, where immigration enforcement, police, and the military all seem wrapped into one oppressive force, and where unapologetic racism dictates an entire ideology that works in the shadows to impose its twisted values on the world. When it was conceived and written, it must have felt like an exaggeration; now, watching the final product in 2026, it feels almost like an inevitability. Let’s face it, none of us wants to accept the reality of fascism imposing itself on our daily lives; a movie that forces us to confront it is, unfortunately, bound to feel like a downer. We get enough “doomscrolling” on social media; we can’t be faulted for not wanting more of it when we sit down to watch a movie.

In truth, however, “One Battle” is anything but a downer. Full of comedic flourish, it maintains a rigorous distance that makes it impossible to make snap judgments about its characters, and that makes all the difference – especially with characters like DiCaprio’s protective dad, whose behavior sometimes feels toxic from a certain point of view. And though it’s a movie which has no qualms about showing us terrifying things we would rather not see, it somehow comes off better in the end than it might have done by making everything feel safe.

“Safe” is something we are never allowed to feel in Anderson’s outlandish action adventure, even at an intellectual level; even if we can laugh at some of its over-the-top flourishes or find emotional (or ideological) satisfaction in the way things ultimately play out, we can’t walk away from it without feeling the dread that comes from recognizing the ugly truths behind its satirical absurdities. In the end, it’s all too real, too familiar, too dire for us not to be unsettled. After all, it’s only a movie, but the things it shows us are not far removed from the world outside our doors. Indeed, they’re getting closer every day.

Visually masterful, superbly performed, and flawlessly delivered by a cinematic master, it’s a movie that, like it or not, confronts us with the discomforting reality we face, and there’s nobody to save it from us but ourselves.

Movies

Few openly queer nominees land Oscar nominations as ‘Sinners’ and ‘One Battle After Another’ lead the pack

‘Wicked: For Good’ landed zero nominations in a shocking downfall from the first film’s 10 nods

This year’s Oscar nominees feature very few openly queer actors or creatives, with KPop Demon Hunters, Come See Me in the Good Light, and Elio bringing some much-needed representation to the field.

KPop Demon Hunters, which quickly became a worldwide sensation after releasing on Netflix last June, was nominated for best animated feature film and best original song for Golden, the chart-topping hit co-written by openly queer songwriter Mark Sonnenblick. Come See Me in the Good Light, a film following the late Andrea Gibson and their wife, Megan Falley, was nominated in the best documentary feature category. Finally, Pixar’s Elio (co-directed by openly queer filmmaker Adrian Molina) was nominated for best animated feature film alongside Zootopia 2, Arco, and Little Amélie or the Character of Rain.

Ethan Hawke did manage to land a best actor nomination for his work in Richard Linklater’s Blue Moon, a biopic that follows a fatal night in Lorenz Hart’s life as he reckons with losing his creative partner, Richard Rodgers. Robert Kaplow was also nominated for best original screenplay for penning the script. Amy Madigan, as expected, was recognized in the best supporting actress category for her work in Weapons, bringing celebrated gay icon Aunt Gladys to the Oscar stage.

While Wicked: For Good was significantly underperforming throughout the season, with Cynthia Erivo missing key nominations and the film falling squarely out of the best picture race early on, most pundits expected the film to still receive some recognition in craft categories. But in perhaps the biggest shock of Oscar nomination morning, For Good received zero nominations — not even for costume design or production design, the two categories in which the first film won just last year. Clearly, there was Wicked fatigue across the board.

There was also reasonable hope that Eva Victor’s acclaimed directorial debut, Sorry, Baby, would land a best original screenplay nod, especially after Julia Roberts shouted out Victor during the recent Golden Globes (which aired the day before Oscar voting started). A24, the studio that distributed Sorry, Baby in the U.S., clearly prioritized campaigns for Marty Supreme (to much success) and Rose Byrne in If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, leaving Sorry, Baby the indie darling that couldn’t quite crack the Oscar race.

However, with the Film Independent Spirit Awards taking place on Feb. 15, queer films like Sorry, Baby, Peter Hujar’s Day, and Twinless will finally get their time to shine. Maybe these films were just underseen, or not given a big enough PR push, but regardless, it’s unfortunate that The Academy couldn’t make room for just one of these when Emilia Pérez managed 13 nominations last year.

Movies

Rise of Chalamet continues in ‘Marty Supreme’

But subtext of ‘American Exceptionalism’ sparks online debate

Casting is everything when it comes to making a movie. There’s a certain alchemy that happens when an actor and character are perfectly matched, blurring the lines of identity so that they seem to become one and the same. In some cases, the movie itself feels to us as if it could not exist without that person, that performance.

“Marty Supreme” is just such a movie. Whatever else can be said about Josh Safdie’s wild ride of a sports comedy – now in theaters and already racking up awards – it has accomplished exactly that rare magic, because the title character might very well be the role that Timothée Chalamet was born to play.

Loosely based on real-life table tennis pro Marty Reisman, who published his memoir “The Money Player” in 1974, this Marty (whose real surname is Mauser) is a first-generation American, a son of Jewish immigrant parents in post-WWII New York who works as a shoe salesman at his uncle’s store on the Lower East Side while building his reputation as a competitive table tennis player in his time off. Cocky, charismatic, and driven by dreams of championship, everything else in his life – including his childhood friend Rachel (Odessa A’zion), who is pregnant with his baby despite being married to someone else – takes a back seat as he attempts to make them come true, hustling every step of the way.

Inevitably, his determination to win leads him to cross a few ethical lines as he goes – such as stealing money for travel expenses, seducing a retired movie star (Gwyneth Paltrow), wooing her CEO husband (Kevin O’Leary) to sponsor him, and running afoul of the neighborhood mob boss (veteran filmmaker Abel Ferrara) – and a chain of consequences piles at his heels, threatening to undermine his success before it even has a chance to happen.

Filmed in 35mm and drenched in the visual style of the gritty-but-gorgeous “New Hollywood” cinema that Safdie – making his solo directorial debut without the collaboration of his brother Benny – so clearly seeks to evoke, “Marty Supreme” calls up unavoidable connections to the films of that era with its focus on an anti-hero protagonist trying to beat the system at its own game, as well as a kind of cynical amorality that somehow comes across more like a countercultural call-to-arms than a nihilistic social commentary. It’s a movie that feels much more challenging in the mid-2020s than it might have four or so decades ago, building its narrative around an ego-driven character who triggers all our contemporary progressive disdain; self-centered, reckless, and single-mindedly committed to attaining his own goals without regard for the collateral damage he inflicts on others in the process, he might easily – and perhaps justifiably – be branded as a classic example of the toxic male narcissist.

Yet to see him this way feels simplistic and reductive, a snap value judgment that ignores the context of time and place while invoking the kind of ethical purity that can easily blind us to the nuances of human behavior. After all, a flawed character is always much more authentic than a perfect one, and Marty Mauser is definitely flawed.

Yet in Chalamet’s hands, those flaws become the heart of a story that emphasizes a will to transcend the boundaries imposed by the circumstantial influences of class, ethnicity, and socially mandated hierarchy. His Marty is a person forging an escape path in a world that expects him to “know his place,” who is keenly aware of the anti-semitism and cultural conventions that keep him locked into a life of limited possibilities and who is willing to do whatever it takes to break free of them; and though he might draw our disapproval for the choices he makes, particularly with regard to his relationship with Rachel, he grows as he goes, navigating a character arc that is less interested in redemption for past sins than it is in finding the integrity to do better the next time – and frankly, that’s something that very few toxic male narcissists ever do.

In truth, it’s not surprising that Chalamet nails the part, considering that it’s the culmination of a project that began in 2018, when Safdie gave him Reisman’s book and suggested collaborating on a movie based on the story of his rise to success. The actor began training in table tennis, and continued to master it over the years, even bringing the necessary equipment to location shoots for movies like “Dune” so that he could perfect his skills – but physical skill aside, he always had what he needed to embody Marty. This is a character who knows what he’s got and is not ashamed to use it, who has the drive to succeed, the will to excel, and the confidence to be unapologetically himself while finding joy in the exercise of his talents, despite how he might be judged by those who see only ego. If any actor could be said to reflect those qualities, it’s Timothée Chalamet.

Other members of the cast also score deep impressions, especially A’zion, whose Rachel avoids tropes of victimhood to achieve her own unconventional character arc. Paltrow gives a remarkably vulnerable turn as the aging starlet who willingly allows Marty into her orbit despite the worldliness that tells her exactly what she’s getting into, while O’Leary embodies the kind of smug corporate venality that instantly positions him as the avatar for everything Marty is trying to escape. Queer fan-fave icons Fran Drescher and Sandra Bernhard also make small-but-memorable appearances, and real-life deaf table tennis player Koto Kawaguchi strikes a memorable chord as the Japanese champion who becomes Marty’s de facto rival.

As for Safdie’s direction, it’s hard to find anything to criticize in his film’s visually stylish, sumptuously photographed (by Darius Khondji), and tightly paced delivery, which makes its two-and-a-half hour runtime fly by without a moment of drag.

It must be said that the screenplay – co-written by Safdie with Ronald Bronstein – leans heavily into an approach in which much of the narrative hinges on implausible coincidences, ironic twists, and a general sense of orchestrated chaos that makes things occasionally feel a little too neat; but let’s face it, life is like that sometimes, so it’s easy to overlook.

What might be more problematic, for some audiences, is Marty’s often insufferable – and occasionally downright ugly behavior. Yes, Chalamet infuses it all with humanizing authenticity, and the story is ultimately more about the character’s emotional evolution than it is about his winning at ping-pong, but it’s impossible not to read a subtext of American Exceptionalism into his winner-takes-all climb to victory – which is why “Marty Supreme,” for all its critical acclaim, is the subject of much heated debate and outrage on social media right now.

As for us, we’re not condoning anything Marty does or says as he hustles his way to the winner’s circle. All we’re saying is that Timothée Chalamet has become an even better actor since he captured our attention (and a lot of gay hearts) in “Call Me By Your Name.”

And that’s saying a lot, because he was pretty great, even then.

-

a&e features4 days ago

a&e features4 days agoAmy Madigan finds herself on the cusp of Oscar glory. Can she overcome the historic bias against horror performances?

-

Television2 days ago

Television2 days ago‘Laid Bare’ isn’t your typical sexy slasher

-

California Politics2 days ago

California Politics2 days ago“I’ve always been an ally.” Seven gubernatorial candidates discuss LGBTQ+ rights at recent forum

-

Commentary4 days ago

Commentary4 days agoLA28: Where is your moral compass?

-

California3 days ago

California3 days agoEquality California has sponsored 12 bills to advance LGBTQ+ rights in the state

-

Books5 days ago

Books5 days agoLove or fear flying you’ll devour ‘Why Fly’

-

a&e features14 hours ago

a&e features14 hours ago‘Another Gay Sequel: Gays Gone Wild!’ and ‘Swan Song’ director Todd Stephens recalls the bygone era of raunchy 2000s comedies

-

a&e features2 days ago

a&e features2 days ago35 years after ‘Truth or Dare,’ Slam is still dancing

-

Photos22 hours ago

Photos22 hours agoPHOTOS: Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras