a&e features

Queery: Hunter Lee Hughes

The multidisciplinary artist answers 20 questions

A sketch of Hunter Lee Hughes by legendary artist Dan Bachardy. (Image provided by Hughes)

Hunter Lee Hughes is a multidisciplinary artist living and working in Los Angeles, best known as a playwright and indie filmmaker whose work comes as an expression of LGBTQ-centric experience. He founded Fatelink in 2004 and StoryAtlas in 2013.

Originally from Houston, he graduated from Trinity University in San Antonio before moving to Los Angeles in pursuit of an acting career. He studied acting with Ivana Chubbuck in her master class for five years, and also spent five years as writer’s assistant to Mardik Martin (co-writer of Martin Scorsese’s “Mean Streets” and “Raging Bull”) – which also amounted to a master class in screenwriting.

He says, “I came to Los Angeles to pursue acting, but at that time it was very difficult for openly gay actors to advance. So, I quickly realized I would need to start making my own work in order to have a creatively satisfying career – well, actually, to have a career, period!”

Pursuing that end, he created “Fate of the Monarchs,” a multi-media one-man show that premiered at Highways Performance Space in 2004 and went on to be a fully realized production in 2005 at NoHo Arts Center. It was chosen as a Critic’s Pick by BackStage West.

A second play, “The Sermons of John Bradley,” was workshopped in 2008, then presented in 2009, and was awarded Best Leading Actor in a Drama (Male) by StageSceneLA.com.

For the screen, he created the gay dark short film “Winner Takes All” in 2011, which starred Alec Mapa and went on to be acquired by Guest House Films for their Black Briefs collection; a year later, he directed the comedy narrative webseries “Dumbass Filmmakers!,” launched in 2012, which won four awards at L.A.WebFest, including Outstanding Directing in a Comedy Series.

His feature directorial debut, “Guys Reading Poems,” came into being after Hunter immersed himself in poetry books left to him by his late grandmother Kathleen. He committed to write and direct a movie with the hope of effectively combining visual poetry with narrative storytelling. The movie had its world premiere at the 21st annual Palm Beach International Film Festival, followed by screenings at Dances With Films and qFLIX Philadelphia. It won the Audience Award for Best Feature (Drama) at the 25th annual Woods Hole Film Festival, the “Creativity in Drama” award at Breckenridge Film Festival and “Best of Fest” at the South Texas Underground Film Festival. It was released across platforms by Gravitas Ventures on Feb. 20, 2018.

“I’ve always been better at dreaming than actually living,” he says, “so I guess I had no choice but to make movies.”

He is currently developing his second feature film, “Inside-Out, Outside-In.”

His newest play, “Nathaniel Quinn: Filmmaker,” focuses on the personal journey of its disillusioned title character, as narrated by the ghost of his dead best friend. It premieres August 31 at Highways Performance Space in Santa Monica.

How long have you been out and who was the hardest person to tell?

I came out at age 18, and like so many gay men, my father was the most difficult person to tell. Now, he’s one of the most supportive!

Who’s your LGBT hero?

Martina Navratilova. She was out before out was cool.

What’s Los Angeles’ best nightspot, past or present?

I had a magical birthday party at the bar at Chateau Marmont one year, so I’ll go with that.

Describe your dream wedding.

55-60 guests in an Emerald Forest kind of theme.

What non-LGBT issue are you most passionate about?

Suicide prevention and treatment for depression. So many good artists are lost needlessly so I believe we need to find a way to be more helpful to those suffering with mental illness or suicidal thoughts.

What historical outcome would you change?

I would go back and make the U.S. government MUCH more responsive right away to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. So many lives could have been saved.

What’s been the most memorable pop culture moment of your lifetime?

The death of Princess Diana.

On what do you insist?

Alone time.

What was your last Facebook post or Tweet?

Promoting this show by posing with my set designer!

If your life were a book, what would the title be?

Between Two Things

If science discovered a way to change sexual orientation, what would you do?

Protest.

What do you believe in beyond the physical world?

I believe in God (singular) and The Casting Gods (plural) and, most days, reincarnation.

What’s your advice for LGBT movement leaders?

Re-read “Twilight of the Golds” and start preparing for that fight. It’s coming.

What would you walk across hot coals for?

The opportunity to make an independent feature film.

What LGBT stereotype annoys you most?

The eunuch gay best friend character.

What’s your favorite LGBT movie?

“Maurice.”

What’s the most overrated social custom?

Wishing people happy birthday over Facebook. At this point, does it really mean anything?

What trophy or prize do you most covet?

Hmmmm….I love that Wimbledon dish that Serena and Martina have won so many times, but I guess I’ll have to wait until a future lifetime to have a crack at that!

What do you wish you’d known at 18?

Make mistakes. But don’t get paralyzed in a destructive pattern. Do what you have to do to break out of those as soon as you can.

Why Los Angeles?

There are lots of creative people here and LA has an open mind toward entrepreneurs, so it’s the right place for me!

BONUS: Favorite poet?

Rumi.

a&e features

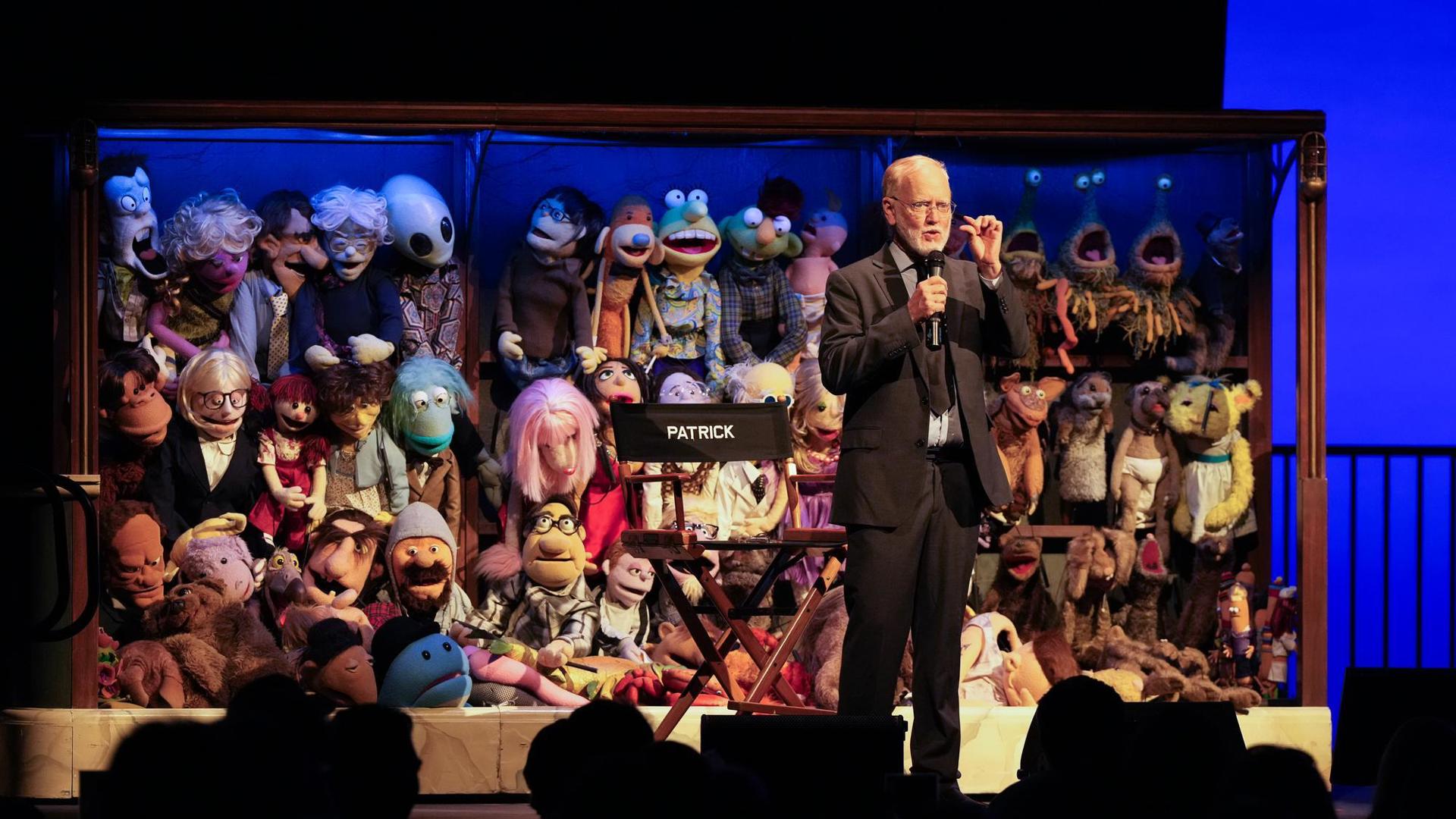

The art of controlled chaos: Patrick Bristow brings the Puppets to life

As co-creator and host of Puppet Up! Uncensored, a wild, “adults-only” improv puppet show developed with Brian Henson of the Jim Henson Company, he combines razor-sharp comedy with next-level puppetry in a way that’s as unpredictable as it is funny.

Whether he’s elbow-deep in puppets or stealing scenes on screen, Patrick Bristow knows how to keep things unapologetically unpredictable and rich with comedy. With decades of improv under his belt and a knack for the unexpected, he proves that comedy and puppetry are best when it’s uncensored.

For over three decades, actor, director, and improv vet Patrick Bristow has been a familiar face across television and film, from his memorable portrayal of Peter on the groundbreaking sitcom Ellen to scene-stealing appearances on Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and more. But Bristow’s creative energy doesn’t stop in front of the camera. As co-creator and host of Puppet Up! Uncensored, a wild, “adults-only” improv puppet show developed with Brian Henson of the Jim Henson Company, he combines razor-sharp comedy with next-level puppetry in a way that’s as unpredictable as it is funny. We chatted with Bristow from his home in Joshua Tree to talk about the show’s origins, the lasting lessons of improv, his unique take on fame, and the true essence of Nellydom.

For our readers who are not yet familiar with the excellence that is Patrick Bristow, could you introduce yourself?

Sure! I’m Patrick Bristow. For most of my 30-some odd years career, I’ve worked as an actor in TV and film, lots of small but memorable roles. But today, I’m here to talk about a show I co-created with Brian Henson of the Jim Henson Company called Puppet Up! Uncensored. It combines brilliant Henson puppeteering with improv comedy. I was in the main company at The Groundlings years ago and have been teaching improv ever since. So this show is a perfect blend of those worlds—kind of a chocolate and peanut butter situation. And we’ve been doing it, on and off, for nearly 20 years.

What’s it like collaborating with Brian Henson?

Brian is incredibly talented, legendary in his own right. Working with him is a dream. We’re both focused on creating the most fun experience possible, both for our audiences and our performers. When we disagree, we figure it out quickly or try both options and go with what works best. There’s no ego involved, just a shared goal.

How did Puppet Up! Uncensored come to life?

Originally, Brian brought me in to teach improv workshops for his puppeteers. He wanted them to gain some of the benefits of improv training—spontaneity, specificity, making bold, immediate choices. We had a group of high-level puppeteers—people whose work you’d definitely recognize, even if you don’t know their names. Some had improv experience already, some didn’t, but they were all great.

After the trial period, Brian asked, “Do you want to keep doing this?” And I said, “Absolutely.” It was really exciting for me to teach improv in a new way because puppeteering requires such a different approach. It wasn’t the same as teaching “fleshies,” as we call human performers in the puppet world.

“Fleshies”?

(Laughs…) Yeah, it sounds a little derogatory, and maybe it is, but I’m standing by it.

If you could create a puppet of any celebrity to add to the show, who would it be?

Oh, that changes weekly! But right now? A Pedro Pascal puppet. If the Henson team could make one as hot as the real Pedro, I’d be thrilled.

Puppet Up! is described as improv meets puppetry… but for adults. How do you balance the humor?

We definitely bring the snark and satire. We try not to get political, because we want a wide spectrum of audiences to enjoy the show. But yes, it can get spicy. And sometimes a little too spicy, at which point I’ll step in as the “schoolmarm” and redirect. The audience often gives us wild suggestions, and we run with it, within reason!

Let’s rewind for a moment back to the ‘90s. You were on Ellen, a show that was way ahead of its time. What was that experience like?

It was thrilling and, at times, scary. There was a bomb threat on set while we were filming the infamous “Puppy Episode” when Ellen came out. I wasn’t there that day, thankfully, but it was intense.

Later that season, when her coming out was being teased, I’d get recognized and even grabbed by strangers in public with questions. That visibility gave me a little taste of what fame feels like, and I realized it wasn’t for me. I liked being the guy who dodged in and out of scenes without the chaos that comes with full-blown celebrity.

So you’d take the work, not the fame?

Exactly. The 18-year-old me wanted to be a TV star. But the 30-something me, and now older, gray-haired me, is content making a living doing what I love. Fame sounds exhausting. I’ll take the bank accounts, though! (laughs)

Speaking of things you love: improv. What’s one thing from improv that people can apply to their everyday lives?

Listening without pre-planning. Really tuning in to what someone is saying, absorbing it emotionally and imaginatively, and then responding authentically. Improv teaches you to focus, to be present, and to let go of control, especially if, like me, you’re a hyperactive overthinker. It’s been a lifesaver for me.

Between performing, teaching, and directing, what role do you connect with most now?

Teaching. And hosting Puppet Up! Hands down. Both involve spontaneous interaction, deep listening, and applying everything I’ve learned. If teaching paid as well as TV work and came with insurance, I’d do it full time.

How have you seen representation in entertainment evolve over the years?

It’s come a long way. We’ve moved beyond the old stereotypes: the “straight-passing gay character” being a compliment to a much richer, more diverse portrayal of identities. I think of people like Titus Burgess, bold, bright, and unapologetically original. When I played Peter on Ellen, my husband said I was “striking a blow for Nellydom,” which I was proud of. That’s me! I’m into Jane Austen, I (try to) play the harp, and I once played Queen Elizabeth I at The Groundlings. If I repped for the Nells, I’m honored.

For readers unfamiliar with the term “Nellydom,” can you enlighten?

It’s the kingdom of femme expression, and unapologetically so. A little swish in your walk, pearls at dinner. Not in-your-face, just not hiding. There’s strength in that. The Nellys were at the frontlines of Stonewall. So yes, I’ll proudly reclaim Nellydom.

Puppet Up! Uncensored runs July 16 – 27th, 2025 at the Kirk Douglas Theatre: Tickets here

a&e features

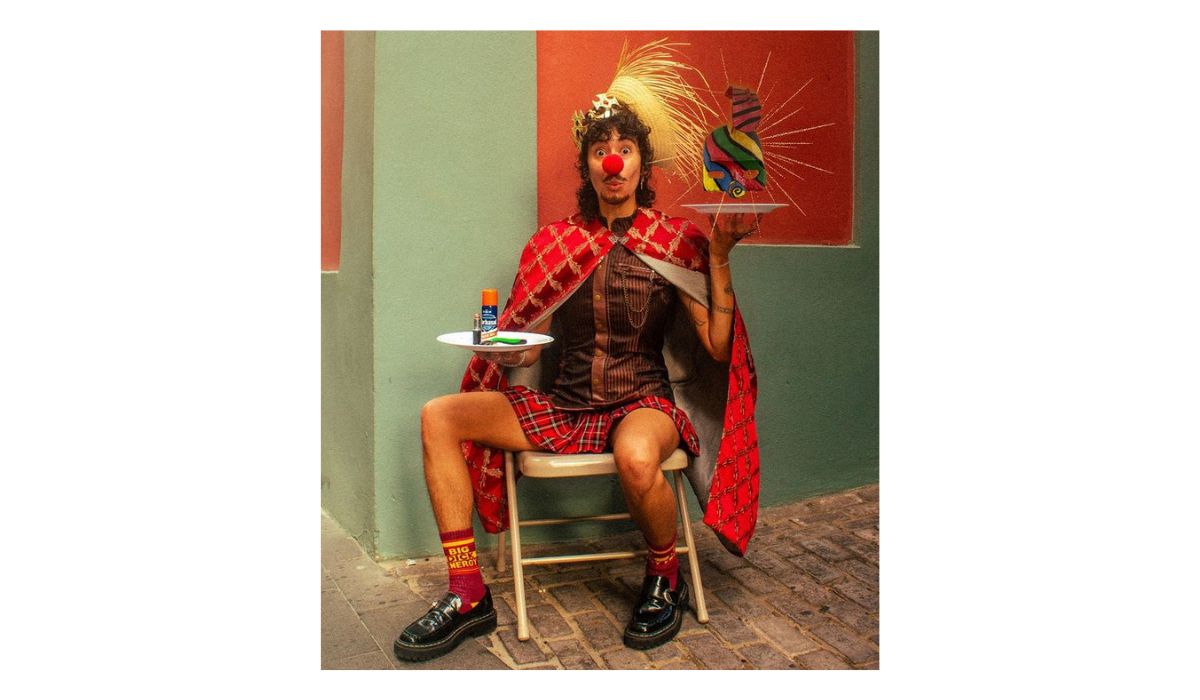

How this Texas drag king reclaimed their identity through Chicano-inspired drag

Three out of ten drag kings who were cast for this first season of King of Drag self-identified as Latinx and after episode two, only one Latinx king remains in the running for the competition.

Buck Wylde, a king from Dallas, Texas delivered a performance that took inspiration from their Catholic upbringing and Catholic school days to put together this persona. During the episode, they shared that they like to “play with religion.”

Murray Hill responded by adding, “sometimes we can’t afford to go to therapy for the Catholic guilt, so we do drag.” Buck Wylde says their therapy and their church is drag.

Buck Wylde, cancer sign, goes by Trigger Mortis when they are outside of drag and present more on the femme side. Along with Big D—another drag king on the series—they are the only two who are more femme outside of their drag persona.

During this episode, Buck Wylde also spoke about the difficulty of performing drag in a red state. They live in conservative Dallas, so they still struggle to find large-scale acceptance and support in the midst of statewide legislation targeting the LGBTQ community in Texas.

“Sometimes it doesn’t feel [as] safe as [I] would like it to be. There’s protesters all the time and we don’t have as many spaces to perform as kings there,” they said in the interview.

Buck Wylde says that for them, the most important thing about drag, is that it is and always has been a protest.

Living in a conservative state is a challenge to them as a drag king, but they say that it’s important for them to stand their ground and not only bring that representation to these areas, but also intentionally keep it there.

“So many people leave Texas for their safety and mental health to go to Portland, LA, or Colorado Springs or you know, anywhere but here.”

During the episode, Buck Wylde also opened up about how their religious background and cultural heritage added an extra layer to their identity issues growing up where they did. Their family wanted them to assimilate and even prevented them from speaking Spanish and they say that through Buck, they are able to re-examine what it means to be a part of that culture.

Buck Wylde is a third generation Mexican-American and they say that though their Spanish is not fluent, they say they do prefer their horchata without (ICE).

“I kind of straddled different worlds there, because I was sort of assimilated but I still had my Mexican culture. I always felt like I wasn’t connected enough because of the assimilation and it was through drag that I was able to reclaim my culture.”

In the first round of competitions for the second episode, the kings broke up into three teams of three for an improv skit where they would have to mansplain a topic and whichever team did it the best—won the group Weenie Challenge.

The winning team included Buck Wylde, Alexander the Great and Henlo Bullfrog. Together they improvised a skit where they mansplained the Amelia Earhart story.

For the solo show, they dressed up as ‘The Devil’ for the improv solo challenge, cracking a joke about how they are dressed like the person currently living in The White House.

Dressed as the Devil, sporting a Zoot Suit for the final competition, Buck Wylde improvised a skit with food.

Buck Wylde says they felt the pressure to perform because along with the other nine kings who were cast, they are the first ten kings to make it to the mainstream and represent king culture.

“We call ourselves the first ten because whatever happens, we’re responsible for how the kings are viewed and how we move forward together, being the blueprint for what’s to come,” said Buck Wylde in an exclusive interview with Los Angeles Blade.

Back stage before the solo improv competition, Buck Wylde says they felt their drag persona “crumbling” away.

They felt like Buck had abandoned them prior to their big moments to prove to the judges that they should stay in the running for the competition. They went up against Perka $exxx, who gave a king-based Dave Chappell performance.

In the end, it was Perka $exxx who received a 4-1 vote from the judges.

Buck Wylde left the show with some advice for the kings and the audience: “No matter what life throws at you, always remember who the Buck you are.”

King of Drag is now available to stream on RevryTV, an LGBTQ streaming platform for queer movies, TV shows, music and more — all for free. New King of Drag episodes will premiere weekly on Sundays.

a&e features

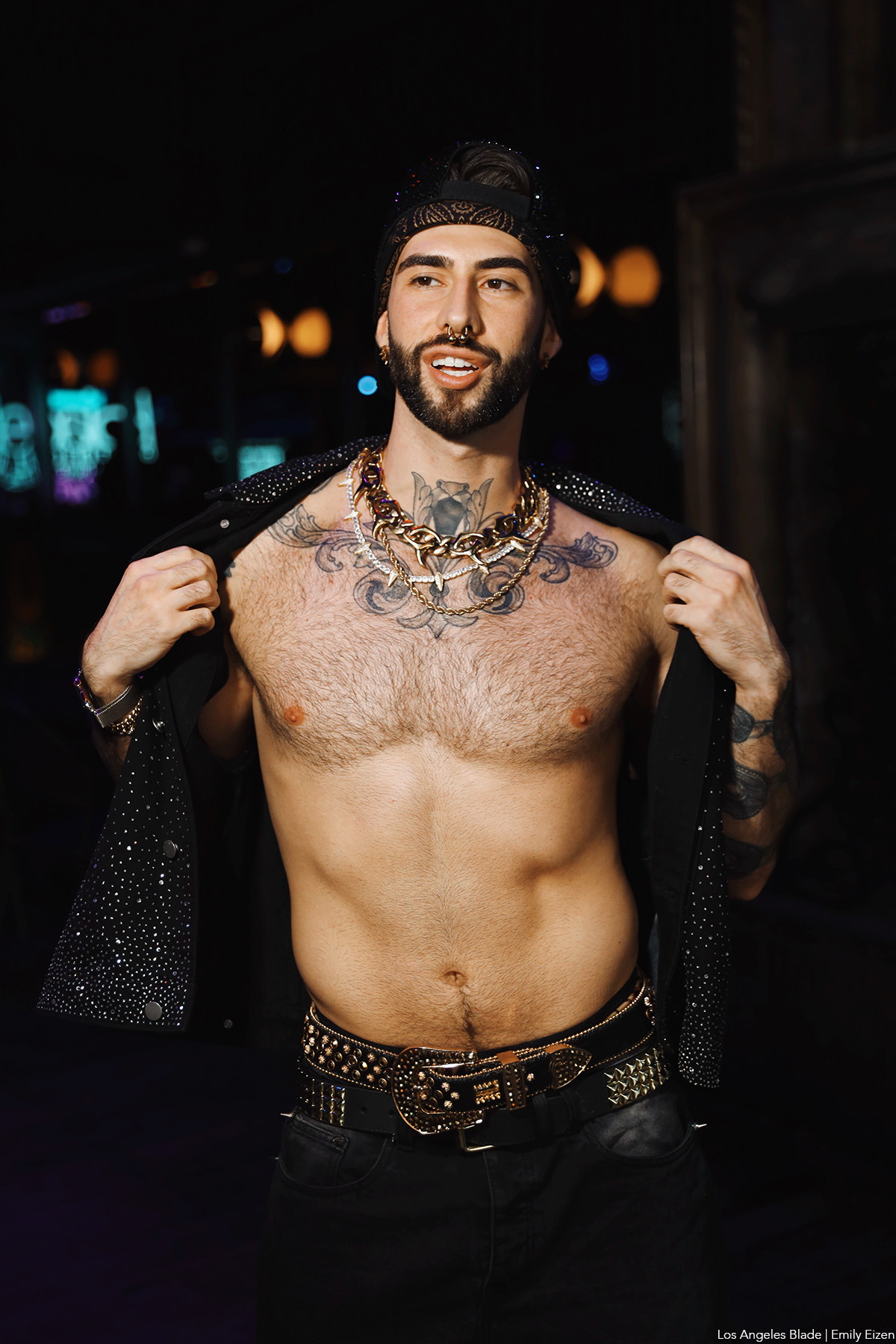

From Drag Race to Dvořák: Thorgy Thor takes the Hollywood Bowl for Classical Pride

This Thursday, the Hollywood Bowl will host the nation’s first Classical Pride, spotlighting LGBTQ+ artists of today and those who have made lasting impacts across centuries of music.

Thorgy Thor is reimagining what a symphony concert can be – queerer, louder, and way more fabulous. Classical music has always been a little gay; Thor is just making it official.

This July 10th, the Hollywood Bowl will be shaking things up with something a lot more fabulous than their usual line-up: Classical Pride, a star-studded celebration of queer excellence in classical music. Conducted by Oliver Zeffman, the program fuses Bernstein and Tchaikovsky with the glittering premiere of Pride Songs, reminding audiences that even the most straight-laced and serious-faced composers had secrets, some of which wore capes and wrote love letters to their (clears throat) roommates.

Enter Thorgy Thor, violinist, drag icon, and reigning monarch of orchestral mischief. Known from RuPaul’s Drag Race and her genre-busting “Thorchestra” shows, Thor is not only crashing the classical music party but redecorating it as she does. Armed with a Juilliard-level command of the violin and a wardrobe that would make Marie Antoinette feel modest, Thor’s been turning symphony stages into something that looks a lot like Studio 54 with better acoustics.

Ahead of her Hollywood Bowl debut, our publisher Alexander Rodriguez caught up with Thor to talk about shattering stereotypes, confusing classical purists, and why drag queens might just be the saviors of a dwindling symphony scene. Spoiler: there will be feathers, fan clacks, and at least one moment of unexpected depth. Because when Thor shows up with a violin and a vengeance, everyone listens, whether they planned to or not.

Some people associate Pride with dance and club music—but not classical. Why do you think that is, and why is it important to change that?

There’s a lot to unpack there. First off, I’m one of those people who definitely associates Pride with music – club music, dancing, parades, rainbow colors, joy. But not many people think of classical music in that context. I’ve been a classical player my whole life, and I’ve also marched in Pride parades. I celebrate both.

The truth is, a lot of people just don’t have access to the history of queerness in classical music. But it’s there. Some of the most prolific composers and conductors – Copland, Tchaikovsky, Bernstein – were gay. Back in the day, let’s be honest, probably everyone was a little bit queer. And since they’re not here to argue it, we get to speculate.

Classical Pride shows are important because they start to bridge that gap. It’s about giving people – especially younger folks – access to stories and voices that have always been part of this tradition but were hidden or unspoken.

How did growing into your identity affect your relationship with music and performance?

I was always immersed in music. My parents supported me with lessons, and I played in orchestras all through school – concertmaster, regional competitions, all that. I was always in the front. But something felt incomplete.

Coming into my queerness, I realized sitting quietly in an orchestra just wasn’t enough. My mind always imagined more – characters, colors, lights, theatrics. I’d be playing Tchaikovsky and thinking, “What if there was a drag artist miming with fans right now?” I needed more than just the music; I needed performance, spectacle, fun.

So I started pushing the dress code. I once showed up in a tux with the pants cut into shorts and bright magenta socks – and the orchestra was not into it. I’d say, “Why do men have to wear stiff bow ties when women get to wear flowy chiffon?” I wanted to challenge tradition, even if it meant getting in trouble. And I often did. But I realized that standing out was inevitable – so I decided to embrace it.

Now, funny enough, Thom Browne and Tom Ford are putting out tuxedos with shorts and high socks. I was just ahead of the trend. You’re welcome.

Why do you think celebrating classical music is important to the queer community right now?

Honestly, orchestras are struggling. Some are shutting down. Audiences are aging. There’s a perception that classical music is stuffy or boring, but it’s not. It’s powerful. It’s emotional. It moves people.

When I perform my “4G” show with symphonies, I always have to win over the orchestra first – they’re incredibly disciplined and talented, but also very skeptical. They’re like, “We just played with Hilary Hahn and Renée Fleming… now who’s this?” But then the show starts, and they see how serious I am about the music and the drag. And afterward, they often say, “That was the most fun I’ve had in 15 years.”

I ask the audience, “Who’s here because of RuPaul’s Drag Race?” Half cheer. Then I ask, “Who’s here because they have season tickets and don’t know who I am?” The other half cheers. That’s the goal: to bring these two very different groups together, laughing and feeling something powerful – together.

What’s your approach to blending these two audiences, drag fans and classical music fans, in one space?

I break the fourth wall. I talk to the audience. I do the first-ever live symphonic walk-off competitions – with Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, feather boas, and fans. I ask, “Who’s 65 and wants to werk?” I get kids up there. I give people drag names. It’s fun, inclusive, and unexpected.

A lot of classical audiences aren’t used to being asked to breathe, let alone unwrap a lozenge. So I set the tone from the top: “Relax, this isn’t that kind of concert.” It creates a space where different generations and communities can laugh together. That’s what I’m proudest of.

Has the current political climate affected your work?

Definitely. Just last month, I was scheduled to perform with the International Pride Orchestra at the Kennedy Center. Then, suddenly, we got dropped – after our president publicly tweeted that he didn’t want any “gay shows” at the Kennedy Center. He threatened to fine them something like $400,000.

Now, he doesn’t run the Kennedy Center, but the pressure worked. They canceled us. It was heartbreaking. Did I respect the decision? Not really. But I understood – they had a whole season to think about. Still, it hurt.

The good news? We moved the show to the Strathmore Theater, and it was incredible. Sold out. The audience showed up, loud and proud. The press was global – Germany, Italy, everywhere. That was beautiful and sad at the same time. That this is what’s making international news. But the show was triumphant.

Tell us about your new show, “Music and Fashion.”

It’s a wild ride – from Bach to Beyoncé. It’s funny, visual, historical, and super interactive. I do about 15 costume changes, some on stage, some on video. We start with a caveperson banging sticks and move through every decade – 1920s, Beatles, Taylor Swift, you name it.

It’s about moments where music and fashion collided and changed everything. From Marie Antoinette to Madonna, and how that relationship evolved. It’s smart, it’s campy, and I’m incredibly proud of it.

What can we expect from your appearance at the Hollywood Bowl’s Classical Pride show?

I’m one part of a bigger lineup that includes Anthony Roth Costanzo, Jamie Barton, Pumeza Matshikiza – some amazing talent. I’ll be performing a cheeky and sexy tango on violin by Jacob Gade, with a little twist in the middle.

I’ll also be doing a live on-stage interview with conductor Oliver Zeffman. Usually conductors show up, wave the baton, and vanish. But I want people to know who’s up there. I warned Oliver I’ll be asking him some left-field questions—and I’m not telling him what they are. It’s going to be fun, a little uncomfortable, and very entertaining.

What does the future look like for queer artists in the arts under this administration?

I’m going to keep doing what I do – being visible, being joyful, and doing it all with color, humor, and discipline. Just existing in this space is an act of rebellion. I don’t need to be political in every show. The work speaks for itself.

Queerness has always been in classical music. I think hundreds of years ago, people were more open than they are now. Today, it’s wild how threatened people get by others simply being happy. I don’t know what’s coming in the next ten years, but I’ll be here, still playing, still dressing up, still making people laugh.

What’s your message to the community this Pride season?

Dare to be different. I get kids coming up to me saying they never thought they could love classical music and be queer at the same time. But they can. You can love two seemingly unrelated things – and do them both fully.

Usually the people who are “too weird” or “too different” are the ones who change the world. And eventually, everyone copies them anyway.

Catch Classical Pride at The Hollywood Bowl Thursday, July 10th at 8 pm. Tickets here.

a&e features

Latina Turner comes to Bring It To Brunch

This fiery Latina drag queen is making her debut at Bring it to Brunch

Get ready West Hollywood. There’s a Colombian heat wave about to hit this weekend. Latina Turner will join the cast of Rocco’s Bring It To Brunch hosted by Cake Moss, this Saturday at 1 p.m. Los Angeles Blade is a proud media sponsor for this fab brunch.

Latina Turner has been doing drag for more than a hot minute and she’s performed all over the nation, bringing her signature humor and killer looks everywhere she goes. We chatted with Turner as she applied her lashes and sipped a cocktail.

What was your first exposure to drag?

My first exposure to drag was when I was 18. I was in Atlanta where I saw Stars of The Century, [which is] the premier, all Black drag show of the South.

How did you come up with your drag name?

My drag name is an homage to my Latin culture and one of my favorite queens Tina Turner, but also to my sense of humor—very tongue-in-cheek, if you will.

What was your first professional gig, how did it go?

My first professional gig was actually for a car commercial. I had been doing drag for 15 minutes, but they had me listed as “real drag queen.” I said if it was real enough for them, it’s real enough for me. I got to test drive a brand new car in full drag and thank god I had that wig pinned in. My lashes were gone with the wind, earrings flew off, but the wig was on.

What sets your drag apart from other queens?

Drag is all about self-expression and artistry. As an artist and creative, my drag is about the delusion of the illusion. In my mind, I could walk down Santa Monica Blvd and not be clocked, but when I perform, it’s about the theatrics and the humor. I also learned to really connect with my audience, something I don’t see too often done. I also bring my Colombian roots and American South upbringing into my character. I think being a first generation, [we] are exposed to two different cultures that don’t normally intersect and the humor from both languages is so…ME!

What do you love most about the drag culture in Los Angeles?

The queer culture of L.A. has always been about resilience from the original gay rights riots at the Black Cat in Silverlake, to the [U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement] (ICE) protests. Drag queen culture isn’t just about the aesthetic and performance style, but also about community and attitude. WeHo queens have this hard work and constant hustle about them, DTLA queens are some of the most creative and entertaining queens and the Eastside queens are some of the most beautiful and hardworking entertainers in the business. No matter what the zip code is, L.A.’s queens and kings have an innate love and passion for performance and to grow as artists and the community really allows you to grow and explore your art.

How can the gay community best support our drag community?

The gay community really needs to understand that drag queens are written in the D.N.A of ALL of gay culture. We as drag queens are under so much pressure to look a certain way and though Drag Race has given the art of drag an incredible amount of visibility, not all drag is “Drag Race” drag. I need you to think of a time when you needed that extra bit of support, whether it was at a bar and wanting to talk to someone, show that same love to these queens. Tip them, share their art and continue to uplift them. Without the drag queens—both young and old—we wouldn’t be the community we are today and we will only continue to thrive if we all rise.

What is your favorite part of doing drag?

Apart from looking fierce and making some cash money, I love the feeling of rocking a performance that you have put so much time and thought into. I think as a drag queen, we overthink some details or we do certain things just for us, so that feeling of “I killed it” is such a high.

What is your least favorite part of doing drag?

My least favorite part of drag….oooof! I think that for me, the tucking (especially tucking the right way), the shaving, and the cost. It hurts my body and my pocket! But hey, beauty is pain, and my drag is never comfortable.

What is your favorite pickup line?

One time, I went up to this guy and asked him, “Do you have any kids… would you want mine?” It was all about the eye contact and body language, LOL.

How do you unwind after a night of drag?

My favorite unwind rituals are a hot shower, a full body scrub, a good moisturizer and retinol, a glass of wine and a sativa pre-roll with my feet up in my comfiest shorts. Untucked and unbothered.

What do you think the future of drag culture looks like?

The future of drag is so exciting! I love that drag is evolving, both aesthetically and performance-wise. Please, baby queens, for the love of God, clean your lace, pluck your hair lines. Marsha didn’t throw a brick for you to look like one.

What can we expect from your appearance at Bring It To Brunch?

This is my Bring It To Brunch Debut! I’m excited to bring a fun, sexy and entertaining vibe to this show! I’m going to give you fashion, exciting and upbeat performances, [all while] smelling like a million bucks.

How has doing drag most changed your life?

I think drag has really taught me so much not just about myself but also how I want to move in the world. Drag has taught me time management, communication skills and skills that are extremely transferable and useful in my day to day job and life. I also love that my drag has taught me how to love myself. Without my drag I wouldn’t have gotten to celebrate my culture or my thick and juicy behind.

Favorite song to perform to:

My absolute favorite song to perform is either “Private Dancer” by Tina Turner or “Nasty Girl” by Inaya Day—both are such strong numbers, but so different and strong!

Craziest drag memory:

My wildest drag memory was last year! I had just performed with Kesha for WeHo Pride and was ready to hit the bars. I was in a ‘lil mall dress and pumps and this girl who had clearly been drinking all day, comes up to me at the bathroom and asks me for a tampon, LOL! I was like, girl you have to be wasted to not see this beard popping through my makeup.

What is your message to the community this Pride season?

Pride started as a riot. Pride is a constant fight and though we are so incredibly lucky to be LGBTQ and even DL in L.A., we have to continue to honor those who came before us and to create a future for those who haven’t had the same luxury of freedom and authenticity. Pride isn’t just getting with hot guys and going to parties it’s about embracing and loving those around us. So get off Grindr and get to the polls! Then you can get all the trade!

Catch Latina Turner at Bring It To Brunch, this Saturday at Rocco’s in West Hollywood.

a&e features

Los Angeles Black Pride raises community consciousness uplifting Black, queer talent

Here is a slice of Pride rooted in ownership, not optics

When most people think of Pride they more often than not relate it to parades parties. Far too many often forget that it is also a platform. Los Angeles Black Pride (LABP) isn’t just raising the flag. They are raising community consciousness at a time when white, mainstream aesthetic often enjoys borrowing from Black, queer culture without acknowledging the appropriation at hand. LABP does the work to flip the script.

This year, the celebration takes a bold economic stance. Visibility is cute, but viability pays the bills.

BLQ+MKT: Not Your Average Pop-Up

Enter BLQ+MKT, LABP’s unapologetically Black, queer vendor marketplace that’s one part business expo, one part cultural homecoming and all of the parts hustle. It’s not just about selling candles and tees, no matter how hard those candles do slap. It’s about building an ecosystem where Black LGBTQ entrepreneurs are seen and supported. This marketplace is not a low-key side attraction — it’s the main stage for economic empowerment.

By centering queer-owned brands, LABP is addressing a long-overdue market correction. Black LGBTQ folks represent a whopping $113 billion in spending power. That’s not just an audience, it’s a full-on economy. And yet, less than 10% of advertising content reflects this reality. BLQ+MKT says what the mainstream won’t — put some respect and revenue on our names.

Lakeyah: Headliner meets head-turner

Speaking of showstoppers, LABP will feature none other than Lakeyah – rapper, baddie, and blueprint for how queer-centered entertainment can drive community dollars. Her presence isn’t just a vibe, it’s part of a larger economic strategy. When you book talent that reflects the community, you do more than just fill seats. You circulate wealth, amplify voices, and make it very clear who this party is really for. She opens for Saucy Santana at this year’s Saturday night main event.

The Business of being seen

LABP is turning Pride into praxis. By shaping spaces where artistry and ownership meet, they’re shifting the focus from being seen to being paid — and paying it forward. This is about building power without waiting around for permission. Applause is adorable. Ownership changes everything.

Come for the music, the joy, the lewks that will leave zero crumbs. And while partaking in all of the Pride, take a closer look. Every booth at BLQ+MKT, every track Lakeyah drops, carries the architecture of a future rooted in Black queer autonomy. In LABP’s world, Pride isn’t solely a performance. It’s a goddamn power move.

To purchase tickets or for more information, head to http://losangelesblackpride.org/

a&e features

On the Fringe: Branden Lee Roth takes on Hollywood

Fresh off his performance in Bat Boy: The Musical, actor Branden Lee Roth is back onstage with yet another show — this time at the Hollywood Fringe Festival in. The show is not only a cabaret-style celebration of the composer’s lesser-known works, but also an opportunity for Roth to perform his powerful vocals and emotional depth.

Tomorrow, the show will have its last two showings at the Hollywood Fringe Festival at 2p.m. and at 10p.m.

“Bat Boy was one of the most challenging [shows] I’ve done — both physically and vocally,” said Roth. The story’s message stuck with him: a character on a profound journey of acceptance and belonging. With such a demanding role — and one carrying so much emotional weight — the pressure was on for Roth to deliver. To make matters more intense, he had little time to prepare.

“I had to jump into the role with minimal rehearsal time,”said Roth. “But the cast and crew were so supportive.”

As the show concluded, he described the performance as a show that will “stay with me forever.”

Now, audiences have yet another chance to see Roth perform — this time in a completely different musical world, but one with just as much passion. Lost & Found offers a rare glimpse into the deep cuts of Frank Wildhorn, the Broadway composer behind Jekyll & Hyde and The Scarlet Pimpernel. However, audiences shouldn’t expect the usual hits.

“The music itself will be something most audiences haven’t heard,” explained Roth. “The show is set up as a cabaret-style with a full band to back it up in an amazing venue.” And it’s not just the instruments or venue that shine.

Roth describes the vocals as “pretty epic.”

Set at The Cat’s Crawl, a speakeasy-style venue, Lost & Found embraces the stripped-down intimacy of cabaret. “Each song stands alonewith no scenes in between outside of some hosting.” It is evident that the opportunity to see Lost & Found live is a chance to really live in the music. There are no flashy sets or scenes between songs — it is purely storytelling through song.

This is Roth’s first time performing in the Hollywood Fringe Festival and he is fully embracing the experience. “The Fringe is an annual celebration of theatre in Hollywood. It’s a really awesome opportunity for creatives and artists to showcase their talents,” he said.

As an openly LGBTQ artist, Roth is no stranger to the challenges of navigating identity in a sometimes rigid or problematic industry. “Being part of the LGBTQ community and being in the arts hasn’t always been an easy journey.” He explains that it took him time to feel confident —specifically when pursuing roles that might not have identified with him. However, Roth recognizes that powerful stories transcend one’s personal identity.

“I start by finding where [a character and I] are similar and build from there.”

Roth encourages folks to get their tickets with only one day left.

“I think audiences are going to really enjoy themselves and leave humming a few new songs to themselves,” he said. You can watch Lost & Found: The Unsung World of Frank Wildhorn at The Cat’s Crawl during the Hollywood Fringe Festival. Tickets are available here, and fans can use the discount code BRANDEN at checkout. To keep up with Roth’s performances, follow him on Instagram at @brandenleeroth.

a&e features

A king rises in Vico Ortiz’s new solo show

With a little bit of ‘astrology woo-woo-ness, a little bit of magic woo-woo-ness, drag and fabulosity,’ they tether together the story of the relationship between them and their mother

Nonbinary, Puerto Rican icon, comedian, actor and activist, Vico Ortiz, 33, binds and weaves awkward childhood moments, family expectations, Walter Mercado and the love of their life embodied by a household mop, to tell the story of the rise of a king.

During the peak of Pride month, Ortiz gifted the Los Angeles queer and trans communities with a spectacularly queer, solo show featuring themself in their quest of self-discovery, a profound sense of connection and reconnection with their femininity and masculinity through growing pains and moments of doubt. This is a show that Ortiz describes as “wholesome, but burlesque.”

King Vico Ortiz rises

The show, which premiered on June 12, details Ortiz’s childhood, vignetting and transforming through their most formative years and through canon events that led them to their gay awakening, such as watching Disney’s Mulan (in Spanish) and the moment Ortiz cut their hair in honor of the scene where Mulan cuts hers off. Ortiz took the audience on a journey through their inner monologue during the moments in their childhood and into adulthood, where they not only come to terms with their identity, but also learn to understand the internal battle their parents went through as they watched their king rise.

Though Ortiz mostly only acted prior to writing and producing their first solo show, they finally took their opportunity to do things a little differently. Last June, their friend Nikki Levy, who runs a show called Don’t Tell My Mother, coached Ortiz to dredge up childhood memories and tether them in a way that could be told and understood by an audience as a show about queerness and self-discovery.

“[Levy] started asking me those questions that dig deeper into the emotional journey of the story, not just ‘hehe’ ‘haha’ moments, but there’s something a little deeper happening,” said Ortiz in an interview with the L.A. Blade. This is when they asked Levy to help coach them through the process of putting the story together in a way that Ortiz imagined it, but also in a way that made sense to the audience.

Ortiz says that with a little bit of ‘astrology woo-woo-ness, a little bit of magic woo-woo-ness, drag and fabulosity,’ they tether together the story of the relationship between them and their mother.

“Astrology had a huge influence in my life growing up from the get-go,” said Ortiz. “I was born and [my mother] printed my birth chart.” The Libra sun, Sagittarius rising, Scorpio moon and Venus in Virgo, says they have always known their chart and that not only did astrology play a huge role in their life growing up, but so did astrologer-to-the-stars Walter Mercado.

The solo was partly influenced by their mother and partly influenced by the iconic, queer, androgynously-elegant Mercado, who famously appeared on TV screens across homes in Latin America and the United States for a segment on that day’s astrological reading.

Seeing Mercado on that daily segment shaped Ortiz’s view of gender and began to understand themselves in a new-found light — one in which they saw their most authentic self.

“Seeing that this person is loved and worshipped by all these people who are like: ‘we don’t care that Walter looks like Walter, we just love Walter,’” said Ortiz. This is when they realized that they too, wanted to be loved and adored by the masses, all while fully embracing their masculinity and femininity.

Closing Night of ‘Rise of a King’

The closing night show of ‘Rise of a King’ was a reminder of how unpredictable life can be and how darkness comes in on some of our brightest moments. Ortiz brilliantly pulled off an improv monologue during a 15-minute power outage. Though it was unpredictable, it was on theme. Ortiz owned the stage, going on about childhood memories that shaped them into who they are today and how they have reconnected with the imaginative child that once told the story of a half-butterfly, half-fish.

The rest of the show went according to plan, immersing the audience in a show that took us straight into the closet of Ortiz’s parents and where Ortiz not only discovered, but learned to embrace who they truly are — to the first moments they embraced the king within and outwardly began to show it to audiences, and eventually their mother.

The set, designed by Jose Matias, functioned as a walk-in closet that transforms throughout the show against the backdrop of drawings of Ortiz and their family memories projected on a big screen on the stage.

Ortiz’s original, solo-show had its world premiere at FUERZAfest in New York City, then its west coast premiere at L.A.’s own Hollywood Fringe Festival.

Follow @puertoricanninja for more updates on their upcoming work.

a&e features

Los Angeles Black Pride: Where trailblazers get their flowers and the next generation gets the blueprint

If you’re looking for receipts, meet three creatives whose glow-up journeys began with LABP and have not lost momentum since

Let’s get one thing straight… or should I say, gay. At Los Angeles Black Pride (LABP), queerness shines brighter than the glitter under the spotlight and struts fiercer than any size 11 stilettos. LABP has long been the beating pulse of Black queer excellence in the City of queer Angels, not just a party but a proving ground. A space where legends are honored, careers are catapulted, and chosen family comes together.

This year’s theme, Legacy & Leadership in Action, is not another Pride month mantra. It’s a whole mood. It serves a reminder that we will not stand idly and wait for our recognition. We create it. And if you’re looking for receipts, meet three creatives whose glow-up journeys began with LABP and have not lost momentum since.

Before they were booked and busy, they participated in Los Angeles Black Pride, a place where Black queer excellence rises, where glam meets grit and where legends are born.

Ebony Lane – Beating Faces and Breaking Barriers

You know when someone walks into a room and suddenly everyone checks their posture? The person walking into that room is Ebony Lane. A Trans make-up artist (MUA) whose brushes do more than blend — they command. Lane’s artistry is lush, precise, and glistening with resilience. She’s made her name crafting unforgettable looks for film, fashion and fierce femmes who command the world’s attention.

But before the gigs, the gloss and the gag-worthy lewks, there was LABP, a space where Lane Lane found alignment between her artistry and her identity. As a longtime fixture in the Crenshaw beauty scene and a pioneer in L.A.’s ballroom and pageant community, Lane has used her platform to uplift young Black and trans folks by encouraging them to carry themselves boldly in their own truth. Her presence at LABP was never just about beauty but visibility and leadership. Today, Lane doesn’t just beat faces, she beats the odds flawlessly.

Berkley The Artist – The Soundtrack to the Revolution

Grammy-nominated and gloriously ground-breaking, Berkley The Artist is proof that soul hits differently when it’s sung with purpose. Blending funk, truth, and a whole lot of Black queer excellence, Berkley’s music is equal parts hype and healing. Before the world heard his music, LABP passed him the mic.

As a performer who’s graced both intimate community stages and major music platforms, his rise in the music industry is deeply intertwined with spaces like LABP, that amplify Black queer expression. His artistry both entertains and empowers. Whether through healing lyrics or community-centered collabs, his work is a love letter to liberation.

KJ – The Lens That Loves Us Back

Some people take pictures. KJ tells stories with a camera. The creative force behind My Black Is Gold, KJ’s photography turns everyday Black queer life into poetry for the eyes. His work feels like a love letter and a clapback all in one — soft and defiant all at the same time.

He first learned to capture folks in their full power at LABP.His work, now featured in exhibitions, digital campaigns and community projects, centers the intersection of softness and strength that is so signature to Black queer life. LABP provides a creative ecosystem where self-definition thrives.

These artists are proof that LABP doesn’t just celebrate Pride but cultivates legacy. It’s a space where Black queer brilliance isn’t just exhibited but elevated. It’s where identity and artistry work together. From makeup chairs to music stages, the impact of LABP is alive in every brushstroke, every beat, and every shot. As we honor these artists and uplift the next generation, one thing is clear — the future is Black, the future is queer, and at Los Angeles Black Pride, it is beautifully unstoppable.

a&e features

Cumbiatón returns to Los Angeles right in time for Pride season

‘Que viva la joteria,’ translates roughly to “Let the gayness live”

Healing and uplifting communities through music and unity is the foundation of this event space created by Zacil “DJ Sizzle Fantastic” Pech and Norma “Normz La Oaxaqueña” Fajardo.

For nearly a decade DJ Sizzle has built a reputation in the queer POC and Spanish-speaking undocumented communities for making the space for them to come together to celebrate their culture and partake in the ultimate act of resistance — joy.

Couples, companions, comadres all dance together on the dancefloor at Cumbiatón. (Photo courtesy of Cumbiatón).

Cumbiatón was created during the first Trump administration as a direct response to the erasure, racism, homophobia and xenophobia that was engrained into the administration’s mission for those first four years. Now that the second Trump administration is upon us, the racism, homophobia, transphobia and xenophobia are tenfold.

This event space is a ‘party for the hood, by the hood.’ It is led by women, queer and trans people of color in every aspect of the production process.

The recent fires that burned through Altadena and Pacific Palisades made DJ Sizzle decide to step back from marketing the event in Los Angeles, an area where people had just lost their businesses, homes and where their lives were completely thrown for a loop.

Now they’re back, doubling-down on their mission to bring cumbias, corridos and all the music many of us grew up listening to, to places that are accessible and safe for our communities.

“I started Cumbiatón back in 2016, right after the election — which was weirdly similar because we’re going through it again. And a lot of us come from the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) movement. We were the ones to really push for that to happen along with the DREAM Act.”

DJ Sizzle says that she wanted to create a space out on the streets to celebrate life and come together, because of how mentally and physically taxing it is to be a part of the marginalized communities that were and still are, a major target for ongoing political attacks.

Edwin Soto and Julio Salgado pose for a photo at a Cumbiaton event in 2024. (Photo courtesy of Cumbiatón).

“We need these spaces so that we can kind of refuel and rejoice in each other’s existence,” said DJ Sizzle. “Because we saw each other out on the street a lot, but never did we really have time to sit down, have a drink, talk, laugh. So I found that music was the way to bring people together and that’s how Cumbiatón got started. It was honestly like a movement of political resistance through music.”

DJ Sizzle is an undocumented community organizer who aims to not only bring awareness to the issues that her communities face, but also to make space to celebrate the wins and bond over the music that brings people in Latin America, East L.A., Boyle Heights and the Bay area together.

Julio Salgado, a queer, visionary artist and migrant rights activist from Ensenada, Baja California with roots in Long Beach and the Bay Area, connected with DJ Sizzle over their shared passion in advocating for immigrant rights.

“Cumbiatón was created during the first [Trump] administration, where you know, a lot of people were really bummed out and so what Sizzle wanted to create was a place where people could come together and celebrate ourselves,” said Salgado. “Fast-forward to the second [Trump] administration and we’re here and feel a little bit more like: ‘oh shit, things are bad again.’ But, things have always been bad.”

Salgado is involved with Cumbiatón through his art. He is a mixed-media artist who creates cartoons using his lived experience with his sobriety journey, undocumented status and queer identity.

With a background in journalism from California State University, Long Beach, Salgado documents what activists do in the undocumented spaces he has been a part of throughout his life.

In 2017, Salgado moved back to Long Beach from the Bay Area, and at the time he started doing political artwork and posters for protests against the first Trump administration, but because the nature of that work can be very tiring, he says that he turned to a more uplifting version of his art where he also draws the joy and unity in his communities.

When he and Sizzle linked up to collaborate during that time, he thought he could use his skills to help uplift this brand and bring it to the forefront of the many events that saturate the party landscape.

DJ Sizzle doing her thing on stage, giving the crowd the music they went looking for. (Photo courtesy of Cumbiatón).

“We are familiar with using the dance floor as a way to kind of put the trauma a little bit away just for one night, get together and completely forget,” said Salgado.

Coming from an undocumented background, Salgado and Sizzle say that their experience with their legal status has made them very aware of how to go about the ID-check process at the door for their events.

“When you’re undocumented, you have something called a [High Security Consular Registration (HSCR)] and it’s kind of like your ID and many of these heterosexual clubs would see that and say it was fake,” said Salgado. “But at the gay club, they didn’t care.”

Just being conscious of what that form of ID looks like and knowing that it’s not fake, helps many of the hundreds of people who come through for Cumbiatón, feel just slightly more at ease.

Edwin Soto, who is another community activist and leader in the undocu-queer community, is also involved in the planning and organizing of the event.

In the long journey of making Cumbiatón what it is now, they say that they have all been very intentional about who they bring in, making sure that whoever they are, they also understand the experience of being undocumented and accepted anyway.

“Something that Sizzle and the team have been very intentional about is making sure that [the security at the door] knows that someone might be using their consulate card,” said Soto.

Bringing together this event space is no easy task, considering the fact that their events are deeply thought out, intentional and inclusive of not just people of color, but also people with differing abilities and people who do not reflect the norm in West Hollywood clubs.

“We created the space that we were longing for that we did not see in West Hollywood,” he said. “[Cumbiatón] is what life could really be like. Where women are not harassed by men. Where people are not body-shamed for what they’re wearing.”

When it comes to their lives outside of Cumbiatón and partying, Sizzle says that it does get exhausting and planning the event gets overwhelming.

“It is really difficult, I’m not going to lie,” said DJ Sizzle. “We are at a disadvantage being queer and being undocumented because this administration triggers us to a point that, anyone who is not a part of those identities or marginalized communities would ever be able to understand,” said Sizzle. “There are times where I’m just like: ‘I’m going to cocoon for a little bit’ and then that affects the marketing and the communication.”

Usually, the events bring in hundreds of people who are looking for community, safety and inclusion. (Photo courtesy of Cumbiatón).

That’s a little bit about what goes on behind the scenes — which really shouldn’t come as a surprise for anyone who is out there fighting for basic human rights, while also making the space to party and enjoy themselves.

“I’m really trying to find balance and honestly my life raft are my friends and my community,” she said. “Like, being able to share, being able to have this plática, and be like ‘bitch, I see you and I know its fucked up, but we got each other.’”

Cumbiatón was made with the purpose of making space to include and invite the many different people in these communities who are otherwise sidelined in broader conversations and in party scenes where they are not as inclusive or thoughtful about their attendees.

“How beautiful is it to be queer and listen to rancheras and to norteñas and cumbia, and to just own it,” said Soto.

To join Cumbiatón at their next party, visit their Instagram page.

a&e features

Best of LGBTQ+ LA 2025

Los Angeles Blade honors the best of the city as selected by our readers

The Los Angeles Blade celebrated its eighth annual Best of LGBTQ+ LA Awards with a spectacular show at The Abbey in West Hollywood on May 22, honoring the community’s best and brightest as selected by you, our readers.

The Awards honored our favorite bars, businesses, artists, organizations, and leaders and featured performances by drag queen Cake Moss, musicians Prince Joshua – who took home the awards for Local Musical Artist of the Year and Go-Go of the Year – and Robert Rene, comedian Allison Reese, and West Hollywood poet laureate Brian Sonia-Wallace. Drag artist Billy Francesca and LA Blade publisher Alexander Rodriguez emceed the event.

“We here in LA are excited to reflect our community, so tonight we’re honoring politicians, business owners, nightlife, entertainment, social media, and Billy,” Rodriguez said, opening the show.

One of the biggest winners of the night was queer mogul and “CEO of Everything Gay” Tristan Schukraft, who won LGBTQ Professional of the Year, while the bar he now owns, The Abbey, took Best LGBTQ Bar, and his pharmaceutical-delivery company MISTR took Best LGBTQ-owned business.

“I’m motivated by making change. We have a purpose, and queer entrepreneurs are building a community that makes a difference,” Schukraft said.

Drag artist and activist Pickle, who runs the LA chapter of Drag Story Hour and is West Hollywood’s first drag laureate, gave a moving speech after she was awarded the Local Hero Award, in which she encouraged anyone who’s facing distress to persevere through the darkness.

“Sometimes, just holding on for one more day is all you can do, but that is strength, and you are loved,” she said.

Transgender rights activist, model, and Blade contributor Rose Montoya was honored as Activist of the Year and Influencer of the Year, although she was unable to attend the ceremony.

“This recognition means more than she can express,” said her brother, Prince Joshua, accepting the award on her behalf. “Activism has never been a choice for her. It’s been a necessity. As a trans person, as a person who exists at the intersection of multiple identities, she’s had to fight not just for visibility, but for dignity, safety, and the right to exist. This work is personal. And in a time where hatred is getting louder, in our laws, in our schools, and in our streets, we don’t have the luxury of staying silent.”

Weho Pride notched two wins during the ceremony, including Best Regional Pride and Best LGBTQ Event for its OutLoud Music Festival, which kick off next week.

“We have a big week ahead and hopefully we’ll see you there because Pride starts here, and Pride starts now,” said Jeff Consoletti, Producer of Weho Pride, accepting the award.

The Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles won the award for Best LGBTQ Social Group,

“The Gay Men’s Chorus of LA has been lifting our spirits through song and fighting for community and singing for all our causes since 1979,” said GMCLA Executive Director Lou Spisto, accepting the award. He also noted that the Chorus will honor Schukraft with its Voice Award at its upcoming Dancing Queens Gala June 21 at the Saban Theatre.

Trans Lifeline was awarded Non-Profit of the Year, likely a recognition of the organization’s importance as trans people have come under increasing attack across the country.

“They’ve received an increase in calls to the tune of 300%, so support your trans brothers and sisters,” Rodriguez said, announcing the award.

DJ Cazwell took home the award for best DJ, although a little mix-up had his award read Best Cannabis Retailer, a distinction that actually went to Green Qween. Cazwell spoke about how much he appreciates the community he found after moving to LA from New York.

“I moved here from New York nine years ago and I found a community of DJs who actually support each other here, so I want to shout out the other nominees,” Cazwell said.

That’s a sentiment that was echoed by Best Bartender winner Sumner Mormeneo from Beaches, who moved to LA from Florida.

“My first six months living here was rough. It wasn’t until I got a job at a bar in Weho that it started feeling like home, so thank you,” Mormeneo said.

More than 40 awards were given out in this year’s Best of LGBTQ+ LA. See the complete list of winners.

-

COMMENTARY2 days ago

COMMENTARY2 days agoWhat if doctors could deny you insulin for being gay?

-

Television4 days ago

Television4 days agoICYMI: ‘Overcompensating’ a surprisingly sweet queer treat

-

Breaking News3 days ago

Breaking News3 days agoProject Angel Food loses $340,000 grant to feed people living with HIV

-

Opinions3 days ago

Opinions3 days agoThe psychology of a queer Trump supporter: Navigating identity, ideology, and internal conflict

-

Breaking News3 days ago

Breaking News3 days agoTrump administration sues California over trans student-athletes

-

Living3 days ago

Living3 days agoFaithfully queer: Finding God and growth in Modern Orthodoxy

-

Commentary4 hours ago

Commentary4 hours agoThe Supreme Court’s ‘Don’t Read Gay’ ruling

-

a&e features4 hours ago

a&e features4 hours agoThe art of controlled chaos: Patrick Bristow brings the Puppets to life