a&e features

For Steve Grand, it was always about the music

Fans appreciate the songs and his image

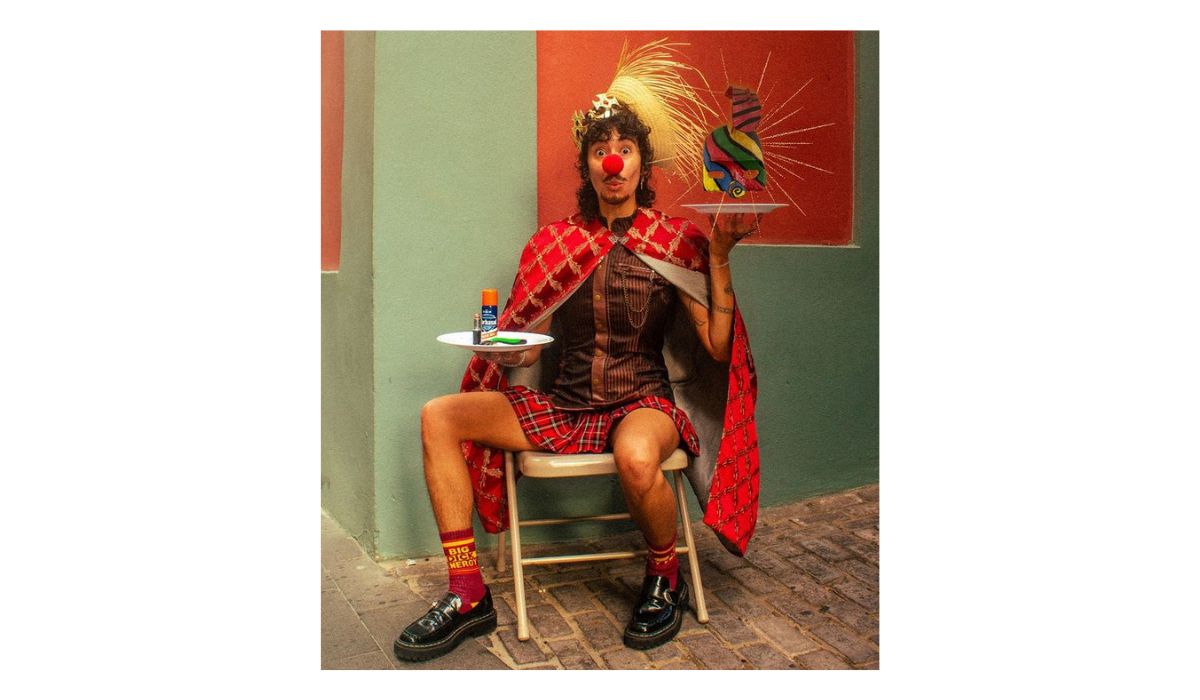

Steve Grand, in association with Chris Isaacson Presents, brings his concert, ‘Up Close & Personal,’ to the Catalina Bar and Grill at 6725 W. Sunset in Hollywood, on Tuesday, February 12, at 8:30 p.m. Tickets available online at ChrisIsaacsonPresents.com or TicketWeb.com, or by phone at (866) 468-3399. (Photo courtesy of Grand)

If you were a member of the LGBTQ community with access to social media in the summer of 2013, you know who Steve Grand is.

That was when the video for his debut song, “All-American Boy,” racked up over a million views only eight days after he posted it on YouTube, and made the unknown singer-songwriter into an instant celebrity.

The self-funded video (Grand maxed out his credit card to have it made) tells the poignant story of a young man in love with his straight male friend and features imagery of country roads, muscle cars and American flags – along with plenty of shirtless footage of its star.

It kicked off a whirlwind of media exposure, not only on the internet but on television shows like “Good Morning America,” and caused enough buzz to make Grand one of the LGBTQ community’s shiniest new lights. He even made Out magazine’s “Out 100” list for the year. Eventually, the video’s popularity was enough to fuel a Kickstarter campaign which allowed Grand to record and release his first complete album – titled “All-American Boy,” of course – in 2015.

Since then, Grand – who will perform at the Catalina Jazz Club here in LA on February 12 – has maintained a slightly lower profile, and the distance in time from the heady viral sensation that made him famous has given him a chance to reflect on the experience.

“It’s something to look back on now,” he says. “It’s almost like talking about a different person, because I’ve grown so much, I’ve changed. It was rough on me, in a lot of ways – when you get a lot of attention all of a sudden, it can be scary, and you feel really vulnerable all the time. I think I still had a lot of things to work through internally, like I was still on shaky ground, just on a personal level. I was still working on my shit.”

After all, sudden fame was a big leap for a kid from a quiet Chicago suburb who had always felt like an outsider growing up.

“I knew I was different from other boys,” Grand reflects. “I was into creative things, I was a little more sensitive, more into arts and music than sports – I always felt different for that reason.”

“Of course, those things don’t mean that you’re gay,” he adds, “but then, when I was about 12 or 13 and I went to my Boy Scouts’ summer camp, I got a crush on my camp counselor.”

“I didn’t know what this feeling was,” he reminisces. “It wasn’t sexual, nothing like that – but I remember wanting to have his attention, to be something special to him. Thinking it over, I realized that, for most of my peers who were boys, it was how they felt about girls – and I was having it about another boy.”

Later, when he was in high school, he went through the painful process of coming out to his conservative Catholic parents.

“There was conflict,” he admits, “but it was with myself – squaring my own values with being gay, and everything I understood about that from growing up Catholic, and from growing up in a household that was definitely more old-fashioned.”

“My parents had me a little later in life than a lot of my peers,” he explains. “They were older, and they weren’t into keeping up with the trends – once they had us their whole world was just about us.”

“My experience tends to have more in common with gay men who are a bit older than I am,” he muses. “10, 20, 30 years older – I feel a connection to them that I don’t always feel with my peers, I think because of my parents being old-fashioned.”

Through all these early years, of course, Grand was already obsessed with music. He started writing songs at 11, and says, “One of the reasons I wanted to make music was so that I could take what I felt, the pain I felt, and turn it into something beautiful. To me, that was always very powerful.”

There was another passion, too – working on his body, something which many of his current fans undoubtedly appreciate. It’s led to Grand being identified in many online profiles as a singer and model, something he disputes.

“I had my photo taken by a couple of photographers, just kind of for fun,” he explains. “It wasn’t my profession, or my aspiration – I was just working on developing my body, and I thought it would be fun to do some photo shoots. I did it all as a hobby.”

He laughs, “I’m as much of a model as any guy on Instagram that takes their shirt off for the camera.”

Even so, Grand has a sex appeal that surely played a role in the big splash of his early success. Even today, his social media profiles – which he describes as “quite active” – are full of Speedo-clad photos of himself, and the beefcake image is an undeniable part of his brand.

Still, for him, it’s always about the music.

Since his “All-American Boy” days, Grand has completed a second album (“Not the End of Me,” released in July of last year); he’s also spent a lot of time performing live, with long-term residencies in Provincetown for the summer, and, most recently, in Puerto Vallarta.

“I would say most of my time is about my live show right now, refining that and getting to be a better musician – right now I’m actually practicing guitar and piano more than I ever have. It’s easy to get lazy, and just rely on people showing up, but I want to make sure that I keep getting better as a live performer.”

He says playing live is satisfying for him in a different way than the long-term process of recording an album.

“So much of that is over a long period of time – there’s no immediacy to it. But this is more immediately gratifying – people come up to me after the show and they say, ‘Oh, I didn’t know what to expect, we really enjoyed it, you’ve made a new fan.’ Even though it’s only one person at a time, it’s just really gratifying to me.”

For his LA appearance next week, Grand returns to a venue he’s played before – and he couldn’t be more thrilled.

“I’m so excited to come to the Catalina Jazz Club,” he gushes. “It really is one of my top three favorite venues I’ve ever played. That piano – it’s one of my favorite pianos that I’ve ever played on, and the sound system is just so good, it’s just a great space.”

“I feel very lucky,” he grins. “I get to do things that I enjoy.”

There’s something heartening about the genuine “gee-whiz” glee in his voice when he says things like this; there’s a gratitude there that lays to rest any notion that Steve Grand might be just another social media poser, looking for validation through fame and fame alone.

“I’m doing what I love now, and that’s all I ever hoped for,” he says, simply. “I never want to sound anything but grateful.”

a&e features

Latina Turner comes to Bring It To Brunch

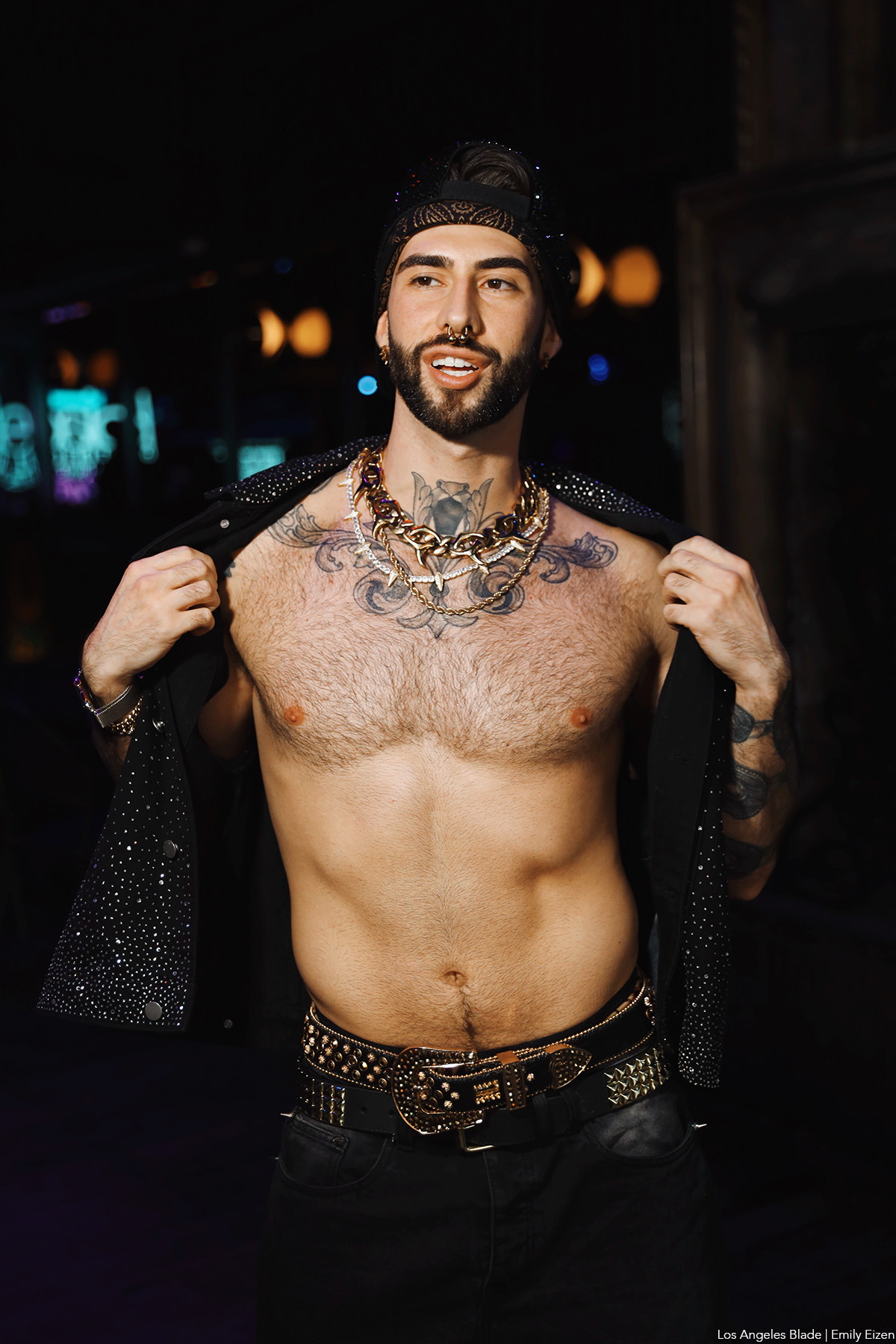

This fiery Latina drag queen is making her debut at Bring it to Brunch

Get ready West Hollywood. There’s a Colombian heat wave about to hit this weekend. Latina Turner will join the cast of Rocco’s Bring It To Brunch hosted by Cake Moss, this Saturday at 1 p.m. Los Angeles Blade is a proud media sponsor for this fab brunch.

Latina Turner has been doing drag for more than a hot minute and she’s performed all over the nation, bringing her signature humor and killer looks everywhere she goes. We chatted with Turner as she applied her lashes and sipped a cocktail.

What was your first exposure to drag?

My first exposure to drag was when I was 18. I was in Atlanta where I saw Stars of The Century, [which is] the premier, all Black drag show of the South.

How did you come up with your drag name?

My drag name is an homage to my Latin culture and one of my favorite queens Tina Turner, but also to my sense of humor—very tongue-in-cheek, if you will.

What was your first professional gig, how did it go?

My first professional gig was actually for a car commercial. I had been doing drag for 15 minutes, but they had me listed as “real drag queen.” I said if it was real enough for them, it’s real enough for me. I got to test drive a brand new car in full drag and thank god I had that wig pinned in. My lashes were gone with the wind, earrings flew off, but the wig was on.

What sets your drag apart from other queens?

Drag is all about self-expression and artistry. As an artist and creative, my drag is about the delusion of the illusion. In my mind, I could walk down Santa Monica Blvd and not be clocked, but when I perform, it’s about the theatrics and the humor. I also learned to really connect with my audience, something I don’t see too often done. I also bring my Colombian roots and American South upbringing into my character. I think being a first generation, [we] are exposed to two different cultures that don’t normally intersect and the humor from both languages is so…ME!

What do you love most about the drag culture in Los Angeles?

The queer culture of L.A. has always been about resilience from the original gay rights riots at the Black Cat in Silverlake, to the [U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement] (ICE) protests. Drag queen culture isn’t just about the aesthetic and performance style, but also about community and attitude. WeHo queens have this hard work and constant hustle about them, DTLA queens are some of the most creative and entertaining queens and the Eastside queens are some of the most beautiful and hardworking entertainers in the business. No matter what the zip code is, L.A.’s queens and kings have an innate love and passion for performance and to grow as artists and the community really allows you to grow and explore your art.

How can the gay community best support our drag community?

The gay community really needs to understand that drag queens are written in the D.N.A of ALL of gay culture. We as drag queens are under so much pressure to look a certain way and though Drag Race has given the art of drag an incredible amount of visibility, not all drag is “Drag Race” drag. I need you to think of a time when you needed that extra bit of support, whether it was at a bar and wanting to talk to someone, show that same love to these queens. Tip them, share their art and continue to uplift them. Without the drag queens—both young and old—we wouldn’t be the community we are today and we will only continue to thrive if we all rise.

What is your favorite part of doing drag?

Apart from looking fierce and making some cash money, I love the feeling of rocking a performance that you have put so much time and thought into. I think as a drag queen, we overthink some details or we do certain things just for us, so that feeling of “I killed it” is such a high.

What is your least favorite part of doing drag?

My least favorite part of drag….oooof! I think that for me, the tucking (especially tucking the right way), the shaving, and the cost. It hurts my body and my pocket! But hey, beauty is pain, and my drag is never comfortable.

What is your favorite pickup line?

One time, I went up to this guy and asked him, “Do you have any kids… would you want mine?” It was all about the eye contact and body language, LOL.

How do you unwind after a night of drag?

My favorite unwind rituals are a hot shower, a full body scrub, a good moisturizer and retinol, a glass of wine and a sativa pre-roll with my feet up in my comfiest shorts. Untucked and unbothered.

What do you think the future of drag culture looks like?

The future of drag is so exciting! I love that drag is evolving, both aesthetically and performance-wise. Please, baby queens, for the love of God, clean your lace, pluck your hair lines. Marsha didn’t throw a brick for you to look like one.

What can we expect from your appearance at Bring It To Brunch?

This is my Bring It To Brunch Debut! I’m excited to bring a fun, sexy and entertaining vibe to this show! I’m going to give you fashion, exciting and upbeat performances, [all while] smelling like a million bucks.

How has doing drag most changed your life?

I think drag has really taught me so much not just about myself but also how I want to move in the world. Drag has taught me time management, communication skills and skills that are extremely transferable and useful in my day to day job and life. I also love that my drag has taught me how to love myself. Without my drag I wouldn’t have gotten to celebrate my culture or my thick and juicy behind.

Favorite song to perform to:

My absolute favorite song to perform is either “Private Dancer” by Tina Turner or “Nasty Girl” by Inaya Day—both are such strong numbers, but so different and strong!

Craziest drag memory:

My wildest drag memory was last year! I had just performed with Kesha for WeHo Pride and was ready to hit the bars. I was in a ‘lil mall dress and pumps and this girl who had clearly been drinking all day, comes up to me at the bathroom and asks me for a tampon, LOL! I was like, girl you have to be wasted to not see this beard popping through my makeup.

What is your message to the community this Pride season?

Pride started as a riot. Pride is a constant fight and though we are so incredibly lucky to be LGBTQ and even DL in L.A., we have to continue to honor those who came before us and to create a future for those who haven’t had the same luxury of freedom and authenticity. Pride isn’t just getting with hot guys and going to parties it’s about embracing and loving those around us. So get off Grindr and get to the polls! Then you can get all the trade!

Catch Latina Turner at Bring It To Brunch, this Saturday at Rocco’s in West Hollywood.

a&e features

Los Angeles Black Pride raises community consciousness uplifting Black, queer talent

Here is a slice of Pride rooted in ownership, not optics

When most people think of Pride they more often than not relate it to parades parties. Far too many often forget that it is also a platform. Los Angeles Black Pride (LABP) isn’t just raising the flag. They are raising community consciousness at a time when white, mainstream aesthetic often enjoys borrowing from Black, queer culture without acknowledging the appropriation at hand. LABP does the work to flip the script.

This year, the celebration takes a bold economic stance. Visibility is cute, but viability pays the bills.

BLQ+MKT: Not Your Average Pop-Up

Enter BLQ+MKT, LABP’s unapologetically Black, queer vendor marketplace that’s one part business expo, one part cultural homecoming and all of the parts hustle. It’s not just about selling candles and tees, no matter how hard those candles do slap. It’s about building an ecosystem where Black LGBTQ entrepreneurs are seen and supported. This marketplace is not a low-key side attraction — it’s the main stage for economic empowerment.

By centering queer-owned brands, LABP is addressing a long-overdue market correction. Black LGBTQ folks represent a whopping $113 billion in spending power. That’s not just an audience, it’s a full-on economy. And yet, less than 10% of advertising content reflects this reality. BLQ+MKT says what the mainstream won’t — put some respect and revenue on our names.

Lakeyah: Headliner meets head-turner

Speaking of showstoppers, LABP will feature none other than Lakeyah – rapper, baddie, and blueprint for how queer-centered entertainment can drive community dollars. Her presence isn’t just a vibe, it’s part of a larger economic strategy. When you book talent that reflects the community, you do more than just fill seats. You circulate wealth, amplify voices, and make it very clear who this party is really for. She opens for Saucy Santana at this year’s Saturday night main event.

The Business of being seen

LABP is turning Pride into praxis. By shaping spaces where artistry and ownership meet, they’re shifting the focus from being seen to being paid — and paying it forward. This is about building power without waiting around for permission. Applause is adorable. Ownership changes everything.

Come for the music, the joy, the lewks that will leave zero crumbs. And while partaking in all of the Pride, take a closer look. Every booth at BLQ+MKT, every track Lakeyah drops, carries the architecture of a future rooted in Black queer autonomy. In LABP’s world, Pride isn’t solely a performance. It’s a goddamn power move.

To purchase tickets or for more information, head to http://losangelesblackpride.org/

a&e features

On the Fringe: Branden Lee Roth takes on Hollywood

Fresh off his performance in Bat Boy: The Musical, actor Branden Lee Roth is back onstage with yet another show — this time at the Hollywood Fringe Festival in. The show is not only a cabaret-style celebration of the composer’s lesser-known works, but also an opportunity for Roth to perform his powerful vocals and emotional depth.

Tomorrow, the show will have its last two showings at the Hollywood Fringe Festival at 2p.m. and at 10p.m.

“Bat Boy was one of the most challenging [shows] I’ve done — both physically and vocally,” said Roth. The story’s message stuck with him: a character on a profound journey of acceptance and belonging. With such a demanding role — and one carrying so much emotional weight — the pressure was on for Roth to deliver. To make matters more intense, he had little time to prepare.

“I had to jump into the role with minimal rehearsal time,”said Roth. “But the cast and crew were so supportive.”

As the show concluded, he described the performance as a show that will “stay with me forever.”

Now, audiences have yet another chance to see Roth perform — this time in a completely different musical world, but one with just as much passion. Lost & Found offers a rare glimpse into the deep cuts of Frank Wildhorn, the Broadway composer behind Jekyll & Hyde and The Scarlet Pimpernel. However, audiences shouldn’t expect the usual hits.

“The music itself will be something most audiences haven’t heard,” explained Roth. “The show is set up as a cabaret-style with a full band to back it up in an amazing venue.” And it’s not just the instruments or venue that shine.

Roth describes the vocals as “pretty epic.”

Set at The Cat’s Crawl, a speakeasy-style venue, Lost & Found embraces the stripped-down intimacy of cabaret. “Each song stands alonewith no scenes in between outside of some hosting.” It is evident that the opportunity to see Lost & Found live is a chance to really live in the music. There are no flashy sets or scenes between songs — it is purely storytelling through song.

This is Roth’s first time performing in the Hollywood Fringe Festival and he is fully embracing the experience. “The Fringe is an annual celebration of theatre in Hollywood. It’s a really awesome opportunity for creatives and artists to showcase their talents,” he said.

As an openly LGBTQ artist, Roth is no stranger to the challenges of navigating identity in a sometimes rigid or problematic industry. “Being part of the LGBTQ community and being in the arts hasn’t always been an easy journey.” He explains that it took him time to feel confident —specifically when pursuing roles that might not have identified with him. However, Roth recognizes that powerful stories transcend one’s personal identity.

“I start by finding where [a character and I] are similar and build from there.”

Roth encourages folks to get their tickets with only one day left.

“I think audiences are going to really enjoy themselves and leave humming a few new songs to themselves,” he said. You can watch Lost & Found: The Unsung World of Frank Wildhorn at The Cat’s Crawl during the Hollywood Fringe Festival. Tickets are available here, and fans can use the discount code BRANDEN at checkout. To keep up with Roth’s performances, follow him on Instagram at @brandenleeroth.

a&e features

A king rises in Vico Ortiz’s new solo show

With a little bit of ‘astrology woo-woo-ness, a little bit of magic woo-woo-ness, drag and fabulosity,’ they tether together the story of the relationship between them and their mother

Nonbinary, Puerto Rican icon, comedian, actor and activist, Vico Ortiz, 33, binds and weaves awkward childhood moments, family expectations, Walter Mercado and the love of their life embodied by a household mop, to tell the story of the rise of a king.

During the peak of Pride month, Ortiz gifted the Los Angeles queer and trans communities with a spectacularly queer, solo show featuring themself in their quest of self-discovery, a profound sense of connection and reconnection with their femininity and masculinity through growing pains and moments of doubt. This is a show that Ortiz describes as “wholesome, but burlesque.”

King Vico Ortiz rises

The show, which premiered on June 12, details Ortiz’s childhood, vignetting and transforming through their most formative years and through canon events that led them to their gay awakening, such as watching Disney’s Mulan (in Spanish) and the moment Ortiz cut their hair in honor of the scene where Mulan cuts hers off. Ortiz took the audience on a journey through their inner monologue during the moments in their childhood and into adulthood, where they not only come to terms with their identity, but also learn to understand the internal battle their parents went through as they watched their king rise.

Though Ortiz mostly only acted prior to writing and producing their first solo show, they finally took their opportunity to do things a little differently. Last June, their friend Nikki Levy, who runs a show called Don’t Tell My Mother, coached Ortiz to dredge up childhood memories and tether them in a way that could be told and understood by an audience as a show about queerness and self-discovery.

“[Levy] started asking me those questions that dig deeper into the emotional journey of the story, not just ‘hehe’ ‘haha’ moments, but there’s something a little deeper happening,” said Ortiz in an interview with the L.A. Blade. This is when they asked Levy to help coach them through the process of putting the story together in a way that Ortiz imagined it, but also in a way that made sense to the audience.

Ortiz says that with a little bit of ‘astrology woo-woo-ness, a little bit of magic woo-woo-ness, drag and fabulosity,’ they tether together the story of the relationship between them and their mother.

“Astrology had a huge influence in my life growing up from the get-go,” said Ortiz. “I was born and [my mother] printed my birth chart.” The Libra sun, Sagittarius rising, Scorpio moon and Venus in Virgo, says they have always known their chart and that not only did astrology play a huge role in their life growing up, but so did astrologer-to-the-stars Walter Mercado.

The solo was partly influenced by their mother and partly influenced by the iconic, queer, androgynously-elegant Mercado, who famously appeared on TV screens across homes in Latin America and the United States for a segment on that day’s astrological reading.

Seeing Mercado on that daily segment shaped Ortiz’s view of gender and began to understand themselves in a new-found light — one in which they saw their most authentic self.

“Seeing that this person is loved and worshipped by all these people who are like: ‘we don’t care that Walter looks like Walter, we just love Walter,’” said Ortiz. This is when they realized that they too, wanted to be loved and adored by the masses, all while fully embracing their masculinity and femininity.

Closing Night of ‘Rise of a King’

The closing night show of ‘Rise of a King’ was a reminder of how unpredictable life can be and how darkness comes in on some of our brightest moments. Ortiz brilliantly pulled off an improv monologue during a 15-minute power outage. Though it was unpredictable, it was on theme. Ortiz owned the stage, going on about childhood memories that shaped them into who they are today and how they have reconnected with the imaginative child that once told the story of a half-butterfly, half-fish.

The rest of the show went according to plan, immersing the audience in a show that took us straight into the closet of Ortiz’s parents and where Ortiz not only discovered, but learned to embrace who they truly are — to the first moments they embraced the king within and outwardly began to show it to audiences, and eventually their mother.

The set, designed by Jose Matias, functioned as a walk-in closet that transforms throughout the show against the backdrop of drawings of Ortiz and their family memories projected on a big screen on the stage.

Ortiz’s original, solo-show had its world premiere at FUERZAfest in New York City, then its west coast premiere at L.A.’s own Hollywood Fringe Festival.

Follow @puertoricanninja for more updates on their upcoming work.

a&e features

Los Angeles Black Pride: Where trailblazers get their flowers and the next generation gets the blueprint

If you’re looking for receipts, meet three creatives whose glow-up journeys began with LABP and have not lost momentum since

Let’s get one thing straight… or should I say, gay. At Los Angeles Black Pride (LABP), queerness shines brighter than the glitter under the spotlight and struts fiercer than any size 11 stilettos. LABP has long been the beating pulse of Black queer excellence in the City of queer Angels, not just a party but a proving ground. A space where legends are honored, careers are catapulted, and chosen family comes together.

This year’s theme, Legacy & Leadership in Action, is not another Pride month mantra. It’s a whole mood. It serves a reminder that we will not stand idly and wait for our recognition. We create it. And if you’re looking for receipts, meet three creatives whose glow-up journeys began with LABP and have not lost momentum since.

Before they were booked and busy, they participated in Los Angeles Black Pride, a place where Black queer excellence rises, where glam meets grit and where legends are born.

Ebony Lane – Beating Faces and Breaking Barriers

You know when someone walks into a room and suddenly everyone checks their posture? The person walking into that room is Ebony Lane. A Trans make-up artist (MUA) whose brushes do more than blend — they command. Lane’s artistry is lush, precise, and glistening with resilience. She’s made her name crafting unforgettable looks for film, fashion and fierce femmes who command the world’s attention.

But before the gigs, the gloss and the gag-worthy lewks, there was LABP, a space where Lane Lane found alignment between her artistry and her identity. As a longtime fixture in the Crenshaw beauty scene and a pioneer in L.A.’s ballroom and pageant community, Lane has used her platform to uplift young Black and trans folks by encouraging them to carry themselves boldly in their own truth. Her presence at LABP was never just about beauty but visibility and leadership. Today, Lane doesn’t just beat faces, she beats the odds flawlessly.

Berkley The Artist – The Soundtrack to the Revolution

Grammy-nominated and gloriously ground-breaking, Berkley The Artist is proof that soul hits differently when it’s sung with purpose. Blending funk, truth, and a whole lot of Black queer excellence, Berkley’s music is equal parts hype and healing. Before the world heard his music, LABP passed him the mic.

As a performer who’s graced both intimate community stages and major music platforms, his rise in the music industry is deeply intertwined with spaces like LABP, that amplify Black queer expression. His artistry both entertains and empowers. Whether through healing lyrics or community-centered collabs, his work is a love letter to liberation.

KJ – The Lens That Loves Us Back

Some people take pictures. KJ tells stories with a camera. The creative force behind My Black Is Gold, KJ’s photography turns everyday Black queer life into poetry for the eyes. His work feels like a love letter and a clapback all in one — soft and defiant all at the same time.

He first learned to capture folks in their full power at LABP.His work, now featured in exhibitions, digital campaigns and community projects, centers the intersection of softness and strength that is so signature to Black queer life. LABP provides a creative ecosystem where self-definition thrives.

These artists are proof that LABP doesn’t just celebrate Pride but cultivates legacy. It’s a space where Black queer brilliance isn’t just exhibited but elevated. It’s where identity and artistry work together. From makeup chairs to music stages, the impact of LABP is alive in every brushstroke, every beat, and every shot. As we honor these artists and uplift the next generation, one thing is clear — the future is Black, the future is queer, and at Los Angeles Black Pride, it is beautifully unstoppable.

a&e features

Cumbiatón returns to Los Angeles right in time for Pride season

‘Que viva la joteria,’ translates roughly to “Let the gayness live”

Healing and uplifting communities through music and unity is the foundation of this event space created by Zacil “DJ Sizzle Fantastic” Pech and Norma “Normz La Oaxaqueña” Fajardo.

For nearly a decade DJ Sizzle has built a reputation in the queer POC and Spanish-speaking undocumented communities for making the space for them to come together to celebrate their culture and partake in the ultimate act of resistance — joy.

Couples, companions, comadres all dance together on the dancefloor at Cumbiatón. (Photo courtesy of Cumbiatón).

Cumbiatón was created during the first Trump administration as a direct response to the erasure, racism, homophobia and xenophobia that was engrained into the administration’s mission for those first four years. Now that the second Trump administration is upon us, the racism, homophobia, transphobia and xenophobia are tenfold.

This event space is a ‘party for the hood, by the hood.’ It is led by women, queer and trans people of color in every aspect of the production process.

The recent fires that burned through Altadena and Pacific Palisades made DJ Sizzle decide to step back from marketing the event in Los Angeles, an area where people had just lost their businesses, homes and where their lives were completely thrown for a loop.

Now they’re back, doubling-down on their mission to bring cumbias, corridos and all the music many of us grew up listening to, to places that are accessible and safe for our communities.

“I started Cumbiatón back in 2016, right after the election — which was weirdly similar because we’re going through it again. And a lot of us come from the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) movement. We were the ones to really push for that to happen along with the DREAM Act.”

DJ Sizzle says that she wanted to create a space out on the streets to celebrate life and come together, because of how mentally and physically taxing it is to be a part of the marginalized communities that were and still are, a major target for ongoing political attacks.

Edwin Soto and Julio Salgado pose for a photo at a Cumbiaton event in 2024. (Photo courtesy of Cumbiatón).

“We need these spaces so that we can kind of refuel and rejoice in each other’s existence,” said DJ Sizzle. “Because we saw each other out on the street a lot, but never did we really have time to sit down, have a drink, talk, laugh. So I found that music was the way to bring people together and that’s how Cumbiatón got started. It was honestly like a movement of political resistance through music.”

DJ Sizzle is an undocumented community organizer who aims to not only bring awareness to the issues that her communities face, but also to make space to celebrate the wins and bond over the music that brings people in Latin America, East L.A., Boyle Heights and the Bay area together.

Julio Salgado, a queer, visionary artist and migrant rights activist from Ensenada, Baja California with roots in Long Beach and the Bay Area, connected with DJ Sizzle over their shared passion in advocating for immigrant rights.

“Cumbiatón was created during the first [Trump] administration, where you know, a lot of people were really bummed out and so what Sizzle wanted to create was a place where people could come together and celebrate ourselves,” said Salgado. “Fast-forward to the second [Trump] administration and we’re here and feel a little bit more like: ‘oh shit, things are bad again.’ But, things have always been bad.”

Salgado is involved with Cumbiatón through his art. He is a mixed-media artist who creates cartoons using his lived experience with his sobriety journey, undocumented status and queer identity.

With a background in journalism from California State University, Long Beach, Salgado documents what activists do in the undocumented spaces he has been a part of throughout his life.

In 2017, Salgado moved back to Long Beach from the Bay Area, and at the time he started doing political artwork and posters for protests against the first Trump administration, but because the nature of that work can be very tiring, he says that he turned to a more uplifting version of his art where he also draws the joy and unity in his communities.

When he and Sizzle linked up to collaborate during that time, he thought he could use his skills to help uplift this brand and bring it to the forefront of the many events that saturate the party landscape.

DJ Sizzle doing her thing on stage, giving the crowd the music they went looking for. (Photo courtesy of Cumbiatón).

“We are familiar with using the dance floor as a way to kind of put the trauma a little bit away just for one night, get together and completely forget,” said Salgado.

Coming from an undocumented background, Salgado and Sizzle say that their experience with their legal status has made them very aware of how to go about the ID-check process at the door for their events.

“When you’re undocumented, you have something called a [High Security Consular Registration (HSCR)] and it’s kind of like your ID and many of these heterosexual clubs would see that and say it was fake,” said Salgado. “But at the gay club, they didn’t care.”

Just being conscious of what that form of ID looks like and knowing that it’s not fake, helps many of the hundreds of people who come through for Cumbiatón, feel just slightly more at ease.

Edwin Soto, who is another community activist and leader in the undocu-queer community, is also involved in the planning and organizing of the event.

In the long journey of making Cumbiatón what it is now, they say that they have all been very intentional about who they bring in, making sure that whoever they are, they also understand the experience of being undocumented and accepted anyway.

“Something that Sizzle and the team have been very intentional about is making sure that [the security at the door] knows that someone might be using their consulate card,” said Soto.

Bringing together this event space is no easy task, considering the fact that their events are deeply thought out, intentional and inclusive of not just people of color, but also people with differing abilities and people who do not reflect the norm in West Hollywood clubs.

“We created the space that we were longing for that we did not see in West Hollywood,” he said. “[Cumbiatón] is what life could really be like. Where women are not harassed by men. Where people are not body-shamed for what they’re wearing.”

When it comes to their lives outside of Cumbiatón and partying, Sizzle says that it does get exhausting and planning the event gets overwhelming.

“It is really difficult, I’m not going to lie,” said DJ Sizzle. “We are at a disadvantage being queer and being undocumented because this administration triggers us to a point that, anyone who is not a part of those identities or marginalized communities would ever be able to understand,” said Sizzle. “There are times where I’m just like: ‘I’m going to cocoon for a little bit’ and then that affects the marketing and the communication.”

Usually, the events bring in hundreds of people who are looking for community, safety and inclusion. (Photo courtesy of Cumbiatón).

That’s a little bit about what goes on behind the scenes — which really shouldn’t come as a surprise for anyone who is out there fighting for basic human rights, while also making the space to party and enjoy themselves.

“I’m really trying to find balance and honestly my life raft are my friends and my community,” she said. “Like, being able to share, being able to have this plática, and be like ‘bitch, I see you and I know its fucked up, but we got each other.’”

Cumbiatón was made with the purpose of making space to include and invite the many different people in these communities who are otherwise sidelined in broader conversations and in party scenes where they are not as inclusive or thoughtful about their attendees.

“How beautiful is it to be queer and listen to rancheras and to norteñas and cumbia, and to just own it,” said Soto.

To join Cumbiatón at their next party, visit their Instagram page.

a&e features

Best of LGBTQ+ LA 2025

Los Angeles Blade honors the best of the city as selected by our readers

The Los Angeles Blade celebrated its eighth annual Best of LGBTQ+ LA Awards with a spectacular show at The Abbey in West Hollywood on May 22, honoring the community’s best and brightest as selected by you, our readers.

The Awards honored our favorite bars, businesses, artists, organizations, and leaders and featured performances by drag queen Cake Moss, musicians Prince Joshua – who took home the awards for Local Musical Artist of the Year and Go-Go of the Year – and Robert Rene, comedian Allison Reese, and West Hollywood poet laureate Brian Sonia-Wallace. Drag artist Billy Francesca and LA Blade publisher Alexander Rodriguez emceed the event.

“We here in LA are excited to reflect our community, so tonight we’re honoring politicians, business owners, nightlife, entertainment, social media, and Billy,” Rodriguez said, opening the show.

One of the biggest winners of the night was queer mogul and “CEO of Everything Gay” Tristan Schukraft, who won LGBTQ Professional of the Year, while the bar he now owns, The Abbey, took Best LGBTQ Bar, and his pharmaceutical-delivery company MISTR took Best LGBTQ-owned business.

“I’m motivated by making change. We have a purpose, and queer entrepreneurs are building a community that makes a difference,” Schukraft said.

Drag artist and activist Pickle, who runs the LA chapter of Drag Story Hour and is West Hollywood’s first drag laureate, gave a moving speech after she was awarded the Local Hero Award, in which she encouraged anyone who’s facing distress to persevere through the darkness.

“Sometimes, just holding on for one more day is all you can do, but that is strength, and you are loved,” she said.

Transgender rights activist, model, and Blade contributor Rose Montoya was honored as Activist of the Year and Influencer of the Year, although she was unable to attend the ceremony.

“This recognition means more than she can express,” said her brother, Prince Joshua, accepting the award on her behalf. “Activism has never been a choice for her. It’s been a necessity. As a trans person, as a person who exists at the intersection of multiple identities, she’s had to fight not just for visibility, but for dignity, safety, and the right to exist. This work is personal. And in a time where hatred is getting louder, in our laws, in our schools, and in our streets, we don’t have the luxury of staying silent.”

Weho Pride notched two wins during the ceremony, including Best Regional Pride and Best LGBTQ Event for its OutLoud Music Festival, which kick off next week.

“We have a big week ahead and hopefully we’ll see you there because Pride starts here, and Pride starts now,” said Jeff Consoletti, Producer of Weho Pride, accepting the award.

The Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles won the award for Best LGBTQ Social Group,

“The Gay Men’s Chorus of LA has been lifting our spirits through song and fighting for community and singing for all our causes since 1979,” said GMCLA Executive Director Lou Spisto, accepting the award. He also noted that the Chorus will honor Schukraft with its Voice Award at its upcoming Dancing Queens Gala June 21 at the Saban Theatre.

Trans Lifeline was awarded Non-Profit of the Year, likely a recognition of the organization’s importance as trans people have come under increasing attack across the country.

“They’ve received an increase in calls to the tune of 300%, so support your trans brothers and sisters,” Rodriguez said, announcing the award.

DJ Cazwell took home the award for best DJ, although a little mix-up had his award read Best Cannabis Retailer, a distinction that actually went to Green Qween. Cazwell spoke about how much he appreciates the community he found after moving to LA from New York.

“I moved here from New York nine years ago and I found a community of DJs who actually support each other here, so I want to shout out the other nominees,” Cazwell said.

That’s a sentiment that was echoed by Best Bartender winner Sumner Mormeneo from Beaches, who moved to LA from Florida.

“My first six months living here was rough. It wasn’t until I got a job at a bar in Weho that it started feeling like home, so thank you,” Mormeneo said.

More than 40 awards were given out in this year’s Best of LGBTQ+ LA. See the complete list of winners.

a&e features

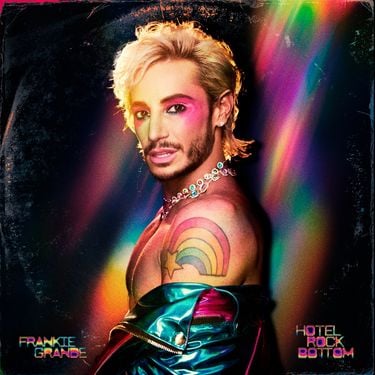

Frankie Grande is loud and proud this WeHo Pride

Frankie Grande will be hitting the stage at this year’s Outloud Music Festival at WeHo Pride and is ready to bring the party

Among other queer and ally big names like Lizzo, Alyssa Edwards, Kim Petras and Frankie Grande will be taking center stage on Saturday, May 31, at this year’s OUTLOUD Music Festival at WeHo Pride. In the wake of the queer community’s current political strife, Grande is taking the spotlight, unapologetically and ready to bring the party, celebrating activism and sexuality unabashedly.

Hot off the heels of his recent two hit singles, “Rhythm of Love” and “Boys,” Grande is gearing up for the release of his new album, Hotel Rock Bottom, hitting platforms on June 27. The album is bringing queer aesthetic to the pop genre and is a retelling of Grande’s life as he has gone from party boy to stage, screen, and reality TV personality, to getting married and living a sober family life (dog and all).

We sat for a chat with Grande as he prepares for his WeHo Pride extravaganza. With everything socially and politically considered, Grande is not holding anything back this Pride season.

Pride is recharging and gearing up for battle. I feel like we’re in a place where our community is under attack, and this is the time where we get the microphone so recharge and get ready to be loud and be prouder than we ever have before. We need to show the world that we are not to be fucked with. We got the mic, so let’s use it.

No stranger to taking the stage, Grande promises a spectacle for his Outloud appearance.

I’m so excited. I’ve put so much effort into crafting a very beautiful show, a very gay show, a very hot show. I’ve selected some really fun songs from my album that people are going to get to hear for the first time because the album won’t be out. I’m also doing some fun and clever covers of songs that have inspired me. I’m excited that I’ve mixed it up and it’s going to be really fun and really gay.

This Pride, Frankie’s call to the gay community is clear.

Support our trans siblings. It is more important than ever. Go to your trans friends and be like, “Hey, what do you need? And how can I help?” Because they’re the ones who are directly being scapegoated at this moment. To think that it’s happening to them means it’s not happening to you is crazy. We are all part of the same community. We’re all under the rainbow umbrella, so let’s go support the community that is directly under attack right now.

Grande’s album comes at a time when queer folk could use a little levity and party attitude. He has been a long-time spokesperson for the LGBTQ community. He has used his platform from reality TV to his role as GLAAD board member to incite activism. He knows full well the fatigue that many of the queer community face as we continue to resist a brutal Presidential administration.

You have to find moments of joy. Honestly, that’s a lot of what this album is to me. It’s like, let’s dance around and bop and be silly to boys tonight so that we can hit the ground running tomorrow and go get some legislation overturned. My whole life, I’ve turned to the dance floor during times of stress, and I think we do need to do that. We have to go celebrate. We have to remember why it is so fun to be a huge homosexual and what we’re fighting for. But then we need to go fight. Don’t get so fucked up that you have to be in bed for three days because we actually do need to go to work.

Grande has also become the poster boy for sober party gays. Celebrating 8 years of sobriety, he has been very open about his journey and how it fits into gay culture. Being openly sober has gained momentum in the queer community and many Prides now include dry events. Grande knows the triggers that Pride can include and has some advice to his fellow sober folk.

First of all, sober gays are fun gays, let’s just say that. If you’re triggered, get the fuck out. You know? There are a lot of drugs, there’s a lot of drinking, there’s a lot of partying, and sometimes you’re just not fully ready to be in those environments. And if that is true, then just leave. The people who are drinking and using will have no idea that you left.

Also go find some sober friends to go with. I did everything in sobriety, like linked with my sober BFFs, Salina EsTitties and stylist Mandoh Melendez. They were my bodyguards and they were my shield, and they had more sobriety than I did. They showed me the ropes, and to this day, they’re still sober and my best friends. So, get a sober buddy and GTFO when you’re triggered, just leave.

Grande is being very vulnerable in his upcoming album Hotel Rock Bottom. Not only is he leaving himself to be compared to other family members in the business, but he is also telling his story on his own terms with music. What is his intent with his album?

My mission with this album is to inspire others to be themselves by being so open and honest. If you just want to listen to the surface value of my album, then you’re going to have a great fun dance time being like, this is so much fun. But if you want to actually go and listen to the lyrics and dissect it, you’ll see that there’s a lot of darkness and a lot of light on both sides of this album. I organized this album into side A and side B, or top and bottom, as we’re calling it on the vinyl. There’s sobriety and using days, there’s good and bad, and highs and lows on both. So, no judgment, it’s all about just be yourself, live your life, live authentically, and you’re going to get through whatever you’re dealing with.

And his message to the queer LA community this Weho Pride?

We’re very privileged and we’re very blessed because we’re in a very liberal and very blue state, so we need to have the best time and show up. But let’s make sure that we’re constantly beaming our love, light, and energy, and thinking about how we can help people in red states who are not going to have a governmentally and a community-supported Pride, because that is a reality these days. Let’s try to figure out how we’re going to help the country while we’re in the most liberal, most protected state in the world, which is fabulous.

Catch Grande onstage at Outloud on Saturday, May 31st. Hotel Rock Bottom will be released June 27th, available wherever you stream your music.

a&e features

New Musical Monday’s host to grace the stage for MISCAST

On Monday, Craig Taggart graces the stage at Mumo’s MISCAST segment

Actor Craig Taggart has had a colorful career that has transported him from St. Louis to Los Angeles.

Taggart made his L.A. stage debut in Del Shores’ revival of “Southern Baptist Sissies” and began a decades-long professional relationship that led to his appearance in a variety of “sordid” incarnations: in repertory in 2006’s Season of Shores in “Sordid Lives,” “Sordid Lives: It’s a Drag,” and then on TV’s “Sordid Lives: The Series” where he made his TV debut.

Los Angeles audiences have been privileged to see Taggart take the stage in a number of sketch comedies and hilarious parodies. One of his most popular runs has been portraying Bette Midler for “Rise n’ Shine” with Midler and Juliette Lewis, a surreal morning talk show hosted by the duo, played by comedy partner Chris Pudlo. Nowhere on Earth would these two stars be hanging out on a TV show, but the pairing works and the result is hilarious. We really would love to see the return of this dynamic duo.

Taggart will step into the emcee shoes this coming week while regular MuMo host Darin Sanone is traveling Europe. Taggart will present the very popular MISCAST edition, a fan-favorite segment of Musical Mondays that features actors performing roles that are far from their intended casting. From gender swaps to reinterpretations, MISCAST at Mumo is often hilarious, and many times poignant. We can’t wait.

We caught up with Taggart to talk about the power of musical theatre, his career and his fascination with divas.

What inspired your early love of musical theatre?

The first time I fell in love, I was in the third grade watching my grammar school’s performance of Cinderella…a leading lady — in this case a pre-teen girl — on stage singing a torchy power ballad. Smitten!

What was your first professional appearance on stage? How did it go?

Made my professional debut in The Miss Kitty’s Saloon Show at Six Flags St. Louis. 6 shows a day and getting to ride roller coasters when your shift is over…best summer job I ever had!

What was your journey from St. Louis to Los Angeles? What took some time getting used to?

There’s a saying in St. Louis: “If you don’t like the weather here, hang out for 24 hours. It’ll change. And boy, would it! What sold me on Los Angeles was the temperate climate all year long. Weather in Missouri is all over the map…the consistency of Mother Nature here in L.A. has helped, pun intended, weather the career fluctuations over the past couple of decades.

How has being part of the theatre changed your life?

I wouldn’t say theatre really changed my life. It defined my life, for the most part. It’s where I first experienced community. It’s where I was allowed to be myself and be celebrated for it.

We need more Bette and Juliet! Any plans to see more of these lovely ladies?

Funny you should mention that…we’ve been tinkering with the idea of bringing those broads back. I think a reunion show would be in order. Seems everyone’s getting a reboot these days…why not those gals?

Gender bending roles in the theatre have become very popular. What role would you cast yourself in?

I would throw a Little Mermaid into oncoming traffic to get to play ‘Ursula’ onstage.

What has been a personal triumph for you in your theatre career and why?

I made my NYC stage debut off-Broadway starring in “Wounded” by Jiggs Burgess and directed by my dear friend Del Shores this past year. Being involved with it from the initial zoom readings to its multiple award-winning run @ The 2023 Hollywood Fringe Festival to it garnering a residency at The SoHo Playhouse as its Overall Excellence Award Winner from the 2024 International Fringe Festival…that has been the cherry on the cake of my career on-stage so far.

What was your first exposure to Musical Mondays?

Wow…I honestly can’t recall my first time. Not that it wasn’t memorable–it just seems so ingrained in my DNA that I find it harder to think of a time when I DON’T recall being exposed to MuMo!

What is it about Musical Mondays that the community loves so much?

I’d say it’s due to the unabashed and unapologetic reverence for the genre.

Why is celebrating musical theatre so important right now?

Celebrating is a ceremony of respect…and with so much vitriol and animosity and negativity in the world these days…this artform–which, at its core, is one rooted in a reality where a story is only able to be told in so many words before it has nowhere else to go but through song–to me that is the purest form of joy. The purest expression of the soul. It’s art in multiple forms. It sings. It dances. It uplifts. It inspires. It unites and it’s defiant. In a world that stresses conformity, where we’re witnessing the ostracization of marginalized groups, it’s this beloved universe that decries “I Am What I Am”–with spotlights and sequins and showtunes–which, in my humble opinion, is the best antidote to all the ugliness we’re currently facing. Musical Theatre has got my undying and eternal respect…and it’s not only my job, but my duty and my honor and my purpose to celebrate it.

What can we expect from your upcoming appearance at MuMo?

To quote Miss M herself: “Did I sing the ballad yet? Was it wonderful?”

What do you love most about performing at MuMo?

Being a part of a crowd that wholeheartedly loves this art form like I do.

What is your message to Mumo fans?

No one says it better than Sondheim…so in my best Ethel, Angela, Tyne, Bernadette, Bette, Patty, & Audra…”Hold your hats, and Hallelujah! Mama’s gonna show it to ya!”

MuMo takes place every Monday at The Chapel at The Abbey; Los Angeles Blade serves as a proud media sponsor

a&e features

Scarlet Vows: A wedding celebration like no other where queer nightlife, love, liberation take center stage

On May 10th, West Hollywood will witness a wedding unlike any other — one that’s equal parts celebration and cultural statement. The Scarlet Vows is a fiery fusion of love, Black queer joy, and unapologetic nightlife, wrapped in a bold, red bow.

Celebrating the union of David Brandyn and Matthew Brinkley, Ph.D., this wedding transcends tradition, turning a day of commitment into a night of unforgettable energy, connection, and liberation. Picture a nightclub alive with lights, music, and bold red gowns swirling on the dance floor. Laughter fills the air, and joy radiates through every glittering detail. This isn’t just a wedding, it’s a love story turned party, turned cultural statement.

“We hate tradition,” said Brandyn, one half of the couple, co-producer of the event, writer and sexual health educator. “We wanted to celebrate in a place that actually feels like us — and that’s the club,” .

Together, he and Brinkley — a relationship therapist and dating coach — have built their careers around supporting Black queer communities.

“We’re not just partners in love — we’re partners in purpose,” explained Brandyn. “This celebration is a tribute to the spaces and people that raised us, healed us, and reminded us we were never alone.”

Their story began, like many queer romances today, with a match on Jack’d.

“But I avoided meeting up,” said Brandyn while laughing. “I knew if we met in person, I’d fall in love — and I wasn’t ready yet.” Brinkley, determined, found another way — showing up at David’s job picnic. As a QTBIPOC couple, the meaning behind this union goes far beyond the personal. “We are what we didn’t see growing up,” said Brandyn. “We’re living proof that Black queer love exists and deserves to be celebrated loudly.”

And that’s exactly what Scarlet Vows is: loud, proud, and deeply intentional. With every detail, the couple is reclaiming what weddings can look like for those of us who’ve been told we’re “too much, too queer, too different.” “We didn’t want perfection or tradition — we wanted sweat, sparkle, laughter, and love,” shared Brandyn. “So we created something that combines a ball, a house party, a love story, and a family reunion.”

The name Scarlet Vows is more than aesthetic. “Scarlet is bold, sexy [and] powerful. Vows are sacred. Together, it’s a declaration: this isn’t love whispered in secret. This is love out loud, in full color, surrounded by chosen family.”

From the moment guests walk in, they’ll be immersed in a world where Black queer joy is not only centered but celebrated. And when they walk out?

“We hope they feel more alive, more hopeful, and more connected to what’s possible,” said Brandyn.

Hosted at Beaches Tropicana, The Scarlet Vows promises an unforgettable night filled with live performances, giveaways, and vendors. The vibe? Elevated, emotional, and full of bold fashion. The dress code is red — think high glam, full drama, and statement-making looks.

But beneath the sequins and spotlight is something even deeper: purpose.

This celebration comes at a time when QTBIPOC communities are facing escalating attacks — politically, socially, and economically. The couple has weathered hardships planning this event too, including being robbed and experiencing sudden venue cancellations. Yet, they’ve persisted — reaching out to community members and aligned brands to co-create something powerful. “Nightlife saved us,” David reflects.

“It gave us safety, friendship, release. This is us giving back. This is joy without apology.” That joy is contagious. Whether you’re a longtime friend or a first-time guest, Scarlet Vows invites everyone to come as they are — whether in a gown, a jockstrap, or both. “Think warmth meets wild,” David smiles. “We want people to cry during the vows and then immediately turn up on the dance floor.”

What happens after the last dance? “Maybe this turns into something bigger,” he muses. “A recurring event, a documentary, a community tradition. Either way, the impact is already bigger than just one night.”

And if you’re still on the fence about attending? “You’ll miss the wedding of the year. A celebration of love, culture, and freedom. A ball, a rave, a healing circle, and a Black queer love story all in one,” said Brandyn. “If you’ve never seen what it looks like when we build something just for us — this is your chance.”

-

Breaking News3 days ago

Breaking News3 days agoMajor victory for LGBTQ funding in LA County

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoKoaty & Sumner: Finding love in the adult industry

-

Books5 days ago

Books5 days agoTwo new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

-

Miscellaneous2 days ago

Miscellaneous2 days agoCan you really find true love in LA? Insights from a queer matchmaker

-

Commentary11 hours ago

Commentary11 hours agoBreaking the mental health mold with Ketamine: insights from creator of Better U

-

El Salvador3 days ago

El Salvador3 days agoLa marcha LGBTQ+ desafía el silencio en El Salvador

-

Arts & Entertainment2 days ago

Arts & Entertainment2 days agoIntuitive Shana gives us her hot take for July’s tarot reading