COMMENTARY

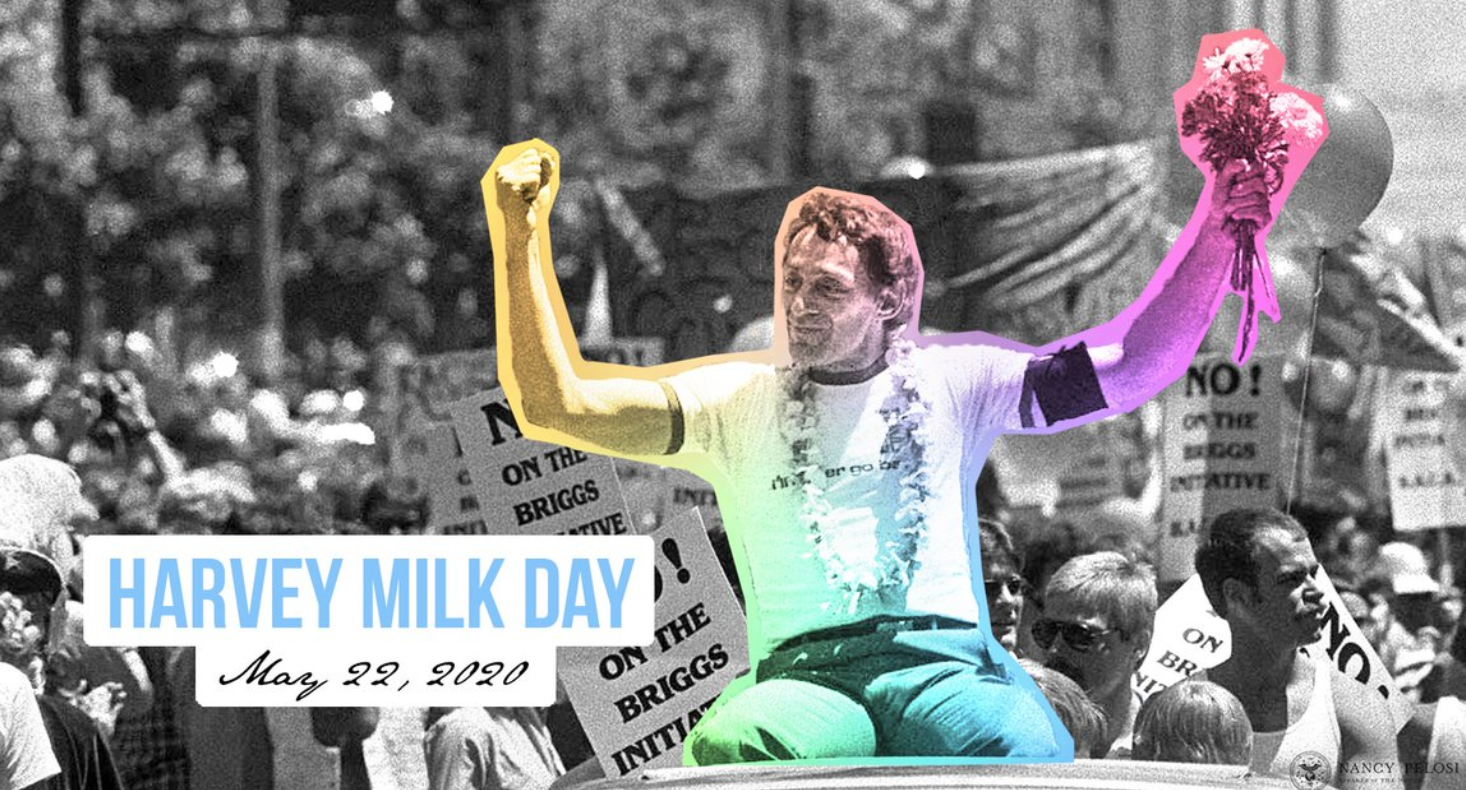

Reporter’s Notebook: landing in history, a commemoration on Harvey Milk Day 2020

As the onslaught of anti-LGBTQI+ animus continues from the Trump administration, particularly targeting the Trans community, this day in celebration of one of California’s early LGBTQI+ pioneers seems almost poignant.

May 22 was designated ‘Harvey Milk Day’ by a law signed in 2009 by then California Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, to commemorate annually the life and legacy of the assassinated LGBTQI equality and civil rights leader.

As the first openly gay person to be elected as a Supervisor to the Board of Supervisors for the City & County of San Francisco, Milk not only advocated for the LGBTQ community but for other minorities and the elderly. Years after his death, Time magazine included Milk on a list titled “The 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century.”

However, on May 21st, 1979, some forty-one years ago, sitting on a jet which had landed at San Francisco International Airport, Harvey Milk was not a name I recognized nor was I aware of his story and importance- but I was about to be educated on that subject matter and in a pretty dramatic fashion.

I was a young, very closeted 20-year-old gay man leaving my home and my country to travel to the City by the Bay at the invitation of my best friend who I’d grown up with in rural Ontario outside of Toronto, Canada. He had moved to the city in February, two and a half months previously.

As my plane taxied up to the gate at around 10 AM that Monday morning, approximately 12 miles north of the terminal, a jury of seven women and five men were deciding the fate of a former colleague of Milk’s, who was on trial for murdering him and then San Francisco Mayor George Moscone. A decision that was to have a significant impact on my life and ultimately my career.

Seven months prior, on November 27, 1978, 32-year-old Dan White crawled through a basement window to avoid the metal detectors located at the entrances to San Francisco’s City Hall. White, a former Supervisor, and ex-city police officer made his way to the second-floor office suites of Mayor Moscone.

In the summer of 1978 White had resigned his supervisor’s seat and now wanted it back. After several minutes of heated argument as he attempted to persuade Moscone to reappoint him- he pulled out a revolver and shot Moscone to death. He then went in search of Harvey Milk who he had repeatedly clashed with especially over issues of LGBTQ rights and then shot him to death. He fled the building only to surrender to SFPD detectives a couple of hours later.

White’s defense team of Douglas Schmidt and Stephen Scherr managed to refocus the trial into an examination of his mental state. Several psychiatrists were called to testy that White had not really meant to commit murder but had been driven to it by stress over finances, loss of the job, and family Then Schmidt highlighted White’s considerable intake of junk food and candy—what came to be known as the “Twinkies Defense“—in which White’s allegedly abnormally high blood sugar count at the time of the murders was blamed for his rampage.

It turned out to be a rather effective defense.

But it was a defense that rendered a lesser finding by the jury of voluntary manslaughter, from which defendant White was sentenced to seven years and eight months of prison time.

Word spread that late afternoon quickly throughout San Francisco, but had the most negative impact in the principally LGBTQ quarter in a city neighborhood district known simply as ‘the Castro.’ It was the area that Milk had represented during his time first as an LGBTQ activist and then later as an elected official.

I was at my friend’s walk-up flat a block away from the intersection of 18th and Castro streets. The phone rang, my friend answered, the next thing I knew I was swept up in the crowds of LGBTQ people appearing in the streets of the Castro and quite angered by the jury’s verdict and the judge’s sentence.

What happened in the next few hours became know as the White Night riots as the LGBTQ population of the city rioted against the injustice not only of the unjust verdict over the killing of a beloved community leader, as well as the mayor but the oppressive and ongoing campaign of persecution by the S.F.P.D. against the LGBTQ community. It was the night before what would have been Milk’s 49th birthday.

In the weeks and months after that night I was fortunate enough to not only meet people who knew Harvey Milk well but in more than a few cases worked with him as activists or in the city government. It was also the event that cast in stone my decision to become a journalist, in part encouraged by Cleve Jones who had protested alongside Milk for LGBTQ equality and rights.

Today would have been Harvey Milk’s 90th birthday, I have long wondered what he would have thought of the transition his beloved LGBTQ community has gone through- marriage equality, the ending of don’t ask don’t tell, but then too at 90 I can also see him still fighting, and still demanding respect and acknowledgment of the humanity of all LGBTQ people.

U. S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi issued this statement Friday saying; “On Harvey Milk Day, people in San Francisco, throughout California and across the country honor a man of extraordinary vision and tenacity, who challenged us all to live with strength, integrity, and courage. As we mark what would have been Harvey’s 90th birthday, we renew our commitment to continue his work by ensuring all people, regardless of who they are or whom they love, can be equal participants in our democracy.

“This year, as our nation faces an unprecedented crisis, Harvey’s message to ‘hope for a better world, hope for a better tomorrow… and hope that all will be alright’ remains as vital as ever. But Harvey was more than a messenger of hope, he was also a clarion voice for action, inspiring generations of leaders, advocates, and ordinary Americans to not just hope for change but to work for it. Thanks in part to Harvey’s trailblazing efforts, our nation has made great progress toward advancing the rights and dignity of the LGBTQ community and all Americans. From helping pass fully inclusive hate crimes legislation and sending the hateful ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ policy into the dustbin of history to ensuring the right to marriage equality, our nation now more fully embodies our founding promise of equality and justice for all.

“This Harvey Milk Day, while we continue to combat the coronavirus threat, we must act boldly, with hope in our hearts, to build on Harvey’s legacy of progress and opportunity. While we work to ensure that every vulnerable community has the support they need to stay healthy and safe, we must also continue to demand that Leader McConnell and Senate Republicans end their year-long obstruction and bring the House-passed Equality Act up for a vote. By finally and fully ending anti-LGBTQ discrimination once and for all, we can honor the life of Harvey Milk and build a brighter future for all Americans.”

Viewpoint

Gay acceptance in US takes a dangerous reversal

Last five years should be wake up call for movement

Shocking news has arrived. New social research says it’s true. Gay, lesbian, gender fluid people, and their allies: we have a problem.

New bias attitude research published by respected social scientists Tessa E.S. Charlesworth and Eli J. Finkel of Northwestern University, based on a longitudinal research program, has shown that gay acceptance in the U.S., which reached its peak about 2020, has taken a deep nosedive in the opposite direction during the last five years. The researchers exclaimed, “This reversal stunned us” — as it did me.

What makes this reversal even more remarkable, as the two social scientists explained, “Americans’ bias against gay people declined faster than any other bias ever tracked in social surveys.” It appears that a new cycle of hetero supremacy has arrived. More likely, the hetero supremacists never went away — just stewing revengefully out of sight around the corner with their buddies from white supremacy and male supremacy.

Analysis of 2.5 million American responses from the beginning of 2021 through 2024 revealed that progress had been turned around. In just four years, anti-gay bias had risen by 10 percent. Researchers followed both explicit bias (to what extent do you prefer straight people over gay people?) and implicit bias (more automatic responses inferred by how rapidly people associate words, such as straight with “good” and gay with “bad.”)

Most disturbing of all, these trends were particularly strong among the youngest American demographic, those under 25, a society’s hopes for the future. Also noteworthy was that anti-gay bias has grown faster among conservatives, but it had also risen among liberals.

The researchers admit they have no idea what is causing this dramatic reversal. They suggest two possible hypotheses: (1) anti-trans bias and (2) fear of gays grooming children to become gay, an essential part of hetero supremacists’ baggage of hate for the past 125 years in the West. Children cannot be groomed into being gay but are born that way for an evolutionary reason (more on that subject in a later article.)

Let me add a third hypothesis based on my close, active involvement and observation as a gay community organizer over the past 60 years. A big part of the problem is gay people themselves. If you have followed my many writings over the past 25 years, you have heard this sermon several times before in varying language and contexts.

The Gay Liberation Revolution (1969-c.1985) taught gay and lesbian people that gay peoples’ self-acceptance and united action are more powerful than hetero supremacy. A Gay Liberation tidal wave provided the momentum for a “movement” forward for our people. Now, that tsunami has become a ripple. How did that happen?

1. The absence of a gay political movement. A political movement is “an organized effort to promote or obtain an end.” There are people who I respect who delusionally speak as if a gay movement still existed. A Gay Liberation template does exist for what a gay movement might look like. It must be played forward, however, with the language, reality and tools of today. It begins with the question: How am I and my community oppressed today by hetero supremacy? Action grows out of oppression.

2. The dominant ideology of gay assimilation. As James Baldwin preached, assimilation is always done on the terms of the dominant culture. For gay people, assimilation implies the eradication of hard-fought-for community and identity. Gay and lesbian people, where did you disappear to? Just yesterday, you were here with your fists in the air.

3. Elite capture of the gay community. This capture is characterized by a top-down power structure (elite vertical axis), community members (grassroots horizontal axis) becoming passive spectators, and the primary priorities being wealth, donors, and celebrities, not community well-being. The call for gay power devolved into donate and consume.

4. Community fragmentation by visual media. The dark side of the current new tech visual media avalanche is the fragmentation of a formerly good-enough-united gay community. Visual media has turned community awareness from “we” to “me.” Local news and investigative journalism have disappeared completely from gay news sites that are now “curated.” A good example was the implosion of Outfest: the LGBTQ Film Festival in L.A., a major community cultural institution for half a century. Gay people found out about that truly shocking community news after Outfest’s disappearance by an investigative journalist at the Hollywood Reporter;the financial malfeasance of GLAAD was uncovered by the New York Times, not gay news sites. Without investigative journalism, community members do not have the information spotlight that is essential for being actively involved and engaged in a healthy community.

5. Pick off the low hanging fruit first. I often hear from others that trans people have taken over the movement. My standard reply: “Because gay and lesbian people have voluntarily disappeared from their political movement, a vacuum has occurred. Vacuums are always filled by something. Trans people are not the problem. There is a problem: your disappearance. The main problem, however, and never forget this, is hetero supremacy.” The hetero supremacists’ playbook is the same used to rescind Roe. Get the low hanging fruit first — under 18 trans youth. Then, proceed calculated step-by-step to the main target — YOU AND ME. Supreme Court Justices Alito and Thomas maladroitly revealed their goals: (1) rescind gay marriage and (2) recriminalize same-sex sexual acts.

A dark night of the gay community’s body and soul might be coalescing. As with all such dark nights, a new sun will rise with renewed vigor and vision, with gay righteous mind and mindfulness replacing today’s mindless scrolling, streaming and surrendering. As the old United Negro College Fund wisely said, “A mind is a terrible thing to waste.”

Don Kilhefner, Ph.D., is a pioneer gay liberationist and a gay community organizer in Los Angeles, nationally and internationally for the past 60 years.

COMMENTARY

If you’re exhausted from dating in 2025, this is how you restart for 2026

What are you going to do differently this year?

If you ended last year feeling like you’ve dated everyone, tried everything, and there’s no one left, I want you to pause for a second because that feeling is incredibly common, especially for gay men.

So let me ask you something, honestly.

What are you going to do differently this year?

Are you just going to get back on the apps again?

Back on Grindr.

Back to the same bars.

Same patterns. Same guys. Same conversations.

And hope somehow this year turns out better?

If you change nothing, nothing changes.

A lot of men I talk to are stuck in this back and forth. Do I want a relationship, or do I just want something casual? Am I ready? Is the timing right? Should I focus on dating or my career? Do I have enough money saved? Am I far enough along in life?

That constant indecision keeps you stuck right where you are.

Then we pile on old rejection, trauma from growing up gay, low self-esteem, and suddenly we start believing we need someone hotter than us, richer than us, more put together than us to feel chosen.

But here’s the part I want you to really hear.

You don’t fall in love with a checklist.

You fall in love with how someone makes you feel.

Do they make you feel safe?

Do you feel calm around them?

Do you feel seen?

Do you laugh together?

Do you feel good being yourself?

That’s what actually builds connection.

Money doesn’t do that.

Abs don’t do that.

A job title doesn’t do that.

Those things can change. They come and go.

So here’s where I’m going to point the finger back to you, in a loving way.

If you’re clear on the kind of man you want, what are you doing to become closer to that person yourself?

If you want someone kind and generous, how are you practicing kindness and generosity in your daily life? Do you volunteer? Do you compliment the person standing next to you even when there’s no attraction? Do you lead with warmth or with judgment?

If you want someone who values family, how much time are you actually spending with yours? Do you prioritize relationships the way you want someone else to?

If you want someone with a full life, hobbies, passions, and friends, what does your life look like right now? Are you doing the things you say you want to do, or are you sitting on the couch thinking about them? You want to play piano. Travel. Hike. Be more active. What steps are you taking to actually live that life?

If you want someone active and adventurous, are you active and adventurous? If you want someone calm, grounded, and emotionally steady, how are you working on becoming grounded yourself? Do you meditate? Do yoga? Take some quiet time? Do anything that regulates your nervous system?

How about finding someone with an amazing body? How does your body look? Are you working out and eating well yourself?

By the way, you can always help your partner get into healthier habits if you are practicing them yourself.

This isn’t about perfection. It’s about alignment.

If you’re expecting someone to check every box while you’re not checking those boxes yourself, that’s not standards. That’s unrealistic expectations.

And remember, our dating pool is already small. Roughly four percent of the male population identifies as gay, bi, queer, or trans. Cut that down to people who are single. Then emotionally available. Then compatible. Then sexually compatible.

The number gets smaller fast.

So maybe this year we stop being so rigid.

Maybe we loosen the rules a little.

Maybe we focus less on the perfect body and more on the right energy.

Chemistry usually doesn’t show up on the first date. Most of the time it doesn’t. So if there’s even just a little attraction, kindness, and curiosity, maybe give it a second date. Maybe slow down long enough to actually see who’s in front of you.

Doing the same thing over and over is not dating. It’s just repeating patterns.

Dating with intention means being honest with yourself first.

If this year you’re ready to stop guessing, stop burning out on apps, and actually have a plan, matchmaking can help. You don’t need more options. You need clarity, accountability, and guidance from someone who understands queer dating and knows how to help you show up as your best self. If you’re serious about doing things differently this year, that’s where matchmaking comes in. Click here and let’s start 2025 right.

Daniel Cooley is a gay matchmaker & co-owner of Best Man Matchmaking – California’s premier service for queer and trans men seeking emotional connections. Learn more here.

Viewpoint

From closeted kid to LGBTQ+ journalist: queer community is my guiding light

Ponderings about my first months at the Blade and the stories shaping my reporting.

In the first week of September, I boarded an early Coast Starlight, crying quietly over a cold bagel as the train departed. It was a 12-hour trip from Emeryville to Los Angeles: plenty of time, I thought, to steep in my sadness as I left the home I had made for the last several years to start a new one in a bright, shiny city. I sat in silence, watching the sun press itself into the sea off the Santa Barbara coast, water and night parting me further and further away from my friends and community.

When I arrived at Union Station, I stood at the platform and was surprised by how warm it was at 9 p.m. A giant skyscraper towered into the sky, glaring down at me with its golden glow and millions of windows. Welcome home.

Since then, I’ve made a truce with the city. I’d always been in its orbit, having grown up in a small, suburban town northeast of it most of my life. But trips into L.A. proper were reserved for special occasions: birthday dinners in Little Tokyo at our favorite restaurant, the now-defunct Sushi Komasa. I had never ventured into the region’s vast queer gems and safe havens: places that I’m sure would have provided me assurance that it was okay to have crushes on people who weren’t boys (or to not have crushes at all!).

As a computer kid, I subsisted on brief explorations on YouTube or clicking through various fanfiction forums. My queerness existed in the gay kiss scene of Cruel Intentions, reigniting with each press of the “play” button and shelved away when the tab closed. I operated like this for years, burying my desires and performing diligent, dependable elder child during the day.

Today, I’m a community reporter at a proudly LGBTQ+ news outlet, where I get to spend most days with other queer folks, listening to their stories and trying to document their lives.

In the last few months, I’ve attended parties, press conferences, community gatherings and rallies that center the liberation of queer folks, specifically those who are multiply marginalized. I’ve spoken with strong leaders and advocates for the TGI movement, who fiercely advocate on a daily basis for greater protections for transgender, gender nonconforming, and intersex people.

One of my most joyous reporting moments at the Blade includes attending the Los Angeles LGBT Center’s annual Queerceañera: where beloved drag diva Lushious Massacr floated across a stage, embraced by the love of her community as she celebrated and reclaimed the coming-of-age ceremony. With queer joy and communal love, she transformed into a beautiful, cascading butterfly on the precipice of flight.

I also attended a transformative HIV/AIDS art exhibition curated by Anuradha Vikram, where a small gallery morphed into a living archive of revolutionary activism spearheaded during the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. The intersections of history and art, and the unity amongst various queer people during this period, were truly inspiring to witness. Speaking with Vikram was instrumental in my early days at the Blade, and our conversation made me think critically about the ways queer activism has shifted dramatically in the decades since the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

How are young, queer people channeling their activism today? This is a question that continues to power my work as I report on our communities.

Another valuable and crucial experience I had while working at the Blade was on World AIDS Day, where I covered a reading by the APLA Health writers group. Dozens of us stood by the pillars of West Hollywood’s AIDS monument and listened to the beautiful, moving prose of several writers who all had personal ties to the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 80s. I still think about John Boucher’s gorgeously crafted, heart-wrenching story.

“I remember Rex coming through our front door after a trip, coming home from work, or at 2:30 in the morning after the bars had closed and he’d finished singing karaoke. As the black lacquer door opened into the goldfish-colored room, he’d sing: ‘Hello apartment,’ Boucher read. “He was greeting our life. His tenor voice was clear and true, his eyes the color of cornflower blue against the pinkish orange sunset of our living room. This is home.”

These stories, rendered through the heartfelt voices of the people around me, remind me of the importance of this work. I struggled with my identity for most of my adolescence and early adulthood, and only began to really accept and understand myself around four years ago, when I began to develop blossoming friendships with queer people who were unabashed about their art, their euphoria, their juicy crushes. Their visibility and their joy, which became our shared visibility and joy, guide me in my most difficult moments.

This year, I suffered the tremendous loss of a dear friend who was a blazing, warm light for her community. She was a poet and artist who was outspoken in her activism and in her bold self-expression. She rejected shame with every fiber of her effervescent being and advocated for the protection of fellow trans women, disabled people, and queer people of color. Her loss is one I will carry with me forever, and anchors me in my work.

My work is for Mercedez, my queer AAPI siblings, queer youth, queer immigrants, queer disabled people, and everyone else who exists on our vast spectrum.

COMMENTARY

The hazards of hating ‘Heated Rivalry’

With public opinion of the LGBTQ community under fire, a show about closeted hockey players and their budding romance has galvanized audiences.

Whether you have heard about the salacious sex scenes, the hype, or the attractive leads, Heated Rivalry has clearly found its place in the zeitgeist. Whether you’ve seen it, love it, hate it, or have strong opinions knowing nothing about it, this show has become a hot topic for the LGBTQ community.

With public opinion of the LGBTQ community under fire, a show about closeted hockey players and their budding romance has galvanized audiences. Based on one of the Game Changers books by Rachel Ried, this series has launched countless memes, TikTok think pieces, and the stars appearing everywhere from Vanity Fair to Hi Tops bar in West Hollywood.

Some of the hot takes include taking issue with the source material being penned by a woman, speculation over the sexual orientation of the stars, and, as actor Jordan Firstman would have us question, is the sex unrealistic? The I Love LA star started beef with his HBO Max coworkers by dragging the show. However, some social media content has quickly squashed the beef. That’s the power of Heated Rivalry.

The question is, why the hate? The fundamental issue is that we end up popping our own balloon. This show and the dialogue surrounding it reveal many blind spots of the gay/queer male community. Drunk on the multiple iterations of Will & Grace and Queer as Folk, we can assume there is an inexhaustible pool of queer content that can break out into the mainstream. We also hold it to impossible standards: not gay enough, too gay, too much sex, not enough.

Heated Rivalry is a love story of two hockey players whose eponymous Heated Rivalry turns to sexual tension, to sex, then maybe…romance? Word of mouth has led to appointment viewing like other signature shows on HBO.

One beef is that people take issue with the fact that it’s focused on athletes. Why this story? Why venerate masculinity? And yet, don’t gay men still venerate masculine and even straight men? There are still gay for pay pornstars, pressure to have the body of an athlete, and an outdated sexual fixation on performative masculinity.

Why not explore the last bastion of homophobia: professional athletics? If someone of Travis Kelsey’s level of fame could come out, wouldn’t that help people stop focusing on queer issues as a reason for the ills of society and maybe look at the real issues?

It’s not surprising, given our political climate, that both Boots and Heated Rivalry would come out around this time. Both explore homophobia and queer men in heteronormative spaces. Major league athletes are still less likely to come out, while the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell has made it easier for queer men to be in the military. They represent widespread appeal to straight communities. After all, where else can a straight man cry and scream than about his favorite sports stars?

Another problematic thing is speculating about the actors’ sexualities. Whether they are queer or not, they are representing our community fairly well. My personal theory is

Connor Storrie is a gifted actor somewhere under the LGBTQ umbrella, and Hudson Williams is a soft heterosexual bottom. Both represent a queer experience.

What matters more is their performances. Storrie learned Russian for the role and has a Meryl Streep-level transformation from an LA actor/model to a Russian athlete with an awe-inspiring caboose. Williams captures so much nuance and holds it down for masculine bottoms.

Finally, who cares if the source material was written by a woman? As queer men, especially gay men, we may rarely interact with women, but we can afford to learn the benefits of integrating emotional and social intelligence, which women are more allowed to cultivate socially.

Ironically, the female fanbase driving up viewership and rhetoric around the show is doing more allyship than a million bachelorette parties at gay bars.

Fundamentally, Heated Rivarly is giving queer men something to gab about and invite discourse in the same way that Drag Race became the Super Bowl of hyperfemininity and helped queers connect and converse. Heated Rivalry offers a tender romance amid the toxic masculinity, intimacy issues, and competition of toxic masculinity.

My personal theory for all the hostility and hot takes about Heated Rivalry is that it centers on yearning. One thing women get permission to do is have a healthy relationship with longing. With queer men, it’s often one-sided and creates this dark addiction to yearning for someone who doesn’t want us. This turns into codependent crushes on your best friend or a hyperfixation on turning a friend with benefits into a partner, all while ignoring the people who want us.

Longing is a slow-building, uncomfortable emotion that explores the range from happiness to sadness. You can try to fuck it away or explain it to bits but for a community inoculated against feelings by the patriarchy, bullies when we were younger and drunk on the power of polyamory and Dan Savage’s countless anti-monogamy talking points, the idea that two men can meet, have a slow budding relationship, build a rapport, develop intimacy slowly over time, and fundamentally realize they want to be together is not the norm. This could be aspirational and may be why the universe inspired a woman to write it, a gay man to develop it into a series, and two actors of indeterminate sexual attractions to play the sex scenes and the emotional angst so we could take a hard look at how we see male love.

COMMENTARY

Why Rob Reiner’s murder hit this old lesbian hippie so hard

Addiction kills. Journalist Karen Ocamb dives into mental health and addiction themes to explore coping with Rob Reiner’s murder.

Rob Reiner was an anomaly in Hollywood: the unabashedly Democratic liberal “good guy” who honestly wanted to dialogue and passionately debate issues such as marriage equality with Republican conservatives as a way of advancing democracy and seeking a more perfect union.

“I’ve always said, ‘You cannot have a healthy democracy unless you have a healthy Republican Party and a healthy Democratic Party so that we can actually debate the ideas of where we are,’” Reiner told Republican political commentator Margaret Hoover, host of PBS’s Firing Line With Margaret Hoover, in a tribute rebroadcast of a show recorded April 2019. “I mean, we are a…capitalist nation, but we also have a lot of socialist programs inside the capitalist nation, and we have to find a way to balance those things. And the only way to do that is to have two parties arguing with a common set of facts.”

Reiner talked about how he befriended many Republicans after Republican legal icon Ted Olson shared his deep belief that marriage is an individual freedom and therefore a fundamental right for lesbian and gay individuals. He reminded Hoover, a longtime LGBTQ+ ally, that they first met at the federal district court in San Francisco for the hearing over California’s anti-gay Prop 8. She excitedly reminded him that they sat together.

Hoover actually served on the Advisory Council for the American Foundation for Equal Rights (AFER), the organization Reiner created with longtime gay friend and fellow progressive advocate Chad Griffin and Griffin’s business partner Kristina Schake. The idea for the federal challenge to Prop 8, which passed with 52 percent of the vote in 2008, started formulating soon thereafter during a lunch with the three and Michele Reiner at the Polo Lounge in the Beverly Hills Hotel. Later, an acquaintance suggested they contact Ted Olson, who supported marriage equality. Reiner shared his excitement when Democratic stalwart David Boies, Olson’s opponent in the infamous 2000 Bush v Gore case, joined the federal case, effectively taking politics out of the argument. (Read New York Times investigative reporter Jo Becker’s book Forcing the Spring: Inside the Fight for Marriage Equality for an engrossing behind-the-scenes look.)

Watching Hoover and Reiner spar, laugh, and exchange stories is a horrific reminder of what we’ve lost. Who else could head up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission after Donald Trump and his acolytes have left the scene?

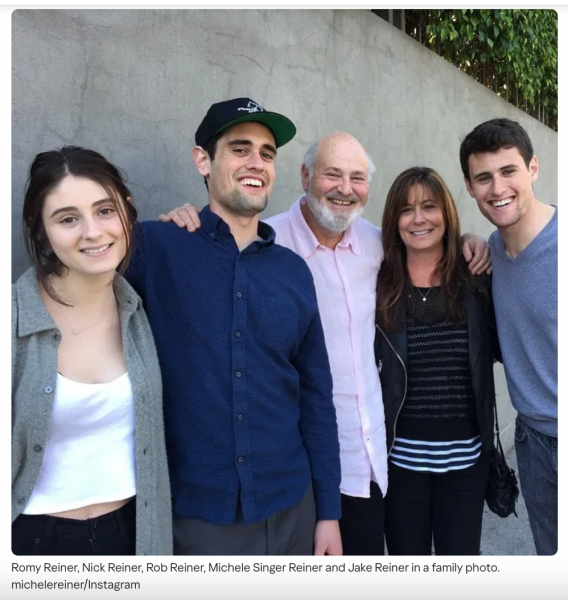

The sudden brutal stabbings of Rob Reiner and his beloved wife Michele in the bedroom of their Brentwood home in the early morning hours of Sunday, Dec. 14, allegedly at the hands of their drug addicted, mentally ill son Nick, hit many of us personally. Through his acting, writing, and incredible films, or through his work on progressive issues, we felt we knew Rob Reiner. And our hearts break for their immediate and extended family.

“Words cannot even begin to describe the unimaginable pain we are experiencing every moment of the day,” Romy Reiner, 27, and Jake Reiner, 34, said in a statement Wednesday. “The horrific and devastating loss of our parents, Rob and Michele Reiner, is something that no one should ever experience. They weren’t just our parents; they were our best friends.”

The siblings requested respect. “We are grateful for the outpouring of condolences, kindness, and support we have received not only from family and friends but people from all walks of life. We now ask for respect and privacy, for speculation to be tempered with compassion and humanity, and for our parents to be remembered for the incredible lives they lived and the love they gave.”

But their request was met with outrageous moral indecency from Trump and click-bait speculation by Megyn Kelly that Nick’s attorney might try the Menendez defense.

While these cruel antics have generally been met with disgust, other human beings are bearing their anguish over the murders and the alleged murderer in silence.

Those who experience mental health issues and their sphere of healthcare providers face heightened uninformed stigma after it was revealed that Nick had been diagnosed with schizophrenia several years ago and his medication had recently been adjusted or changed.

And many in 12 Step communities are bereft. We are excruciatingly familiar with alcoholic/drug addict arrogance, impulsiveness, and the compulsion to get what we need by any means necessary. “I want what I want when I want it – and I want it NOW!”

And this: “An alcoholic is someone who could be lying in a gutter and still look down on someone.”

And then there’s rage that’s so chemically exhilarating, you forget what you’re enraged about.

Whether hooked, self-medicating, or mixing street drugs with pharmaceuticals, there are some drugs that can take a brain hanging ten over a cliff of insanity and tip it over with a whisper or nudge. Some who have fallen don’t get back up. Others don’t want to.

What are loving parents to do?

LSD tipped me over; at the age of 20, I became a ward of the State of Connecticut after an almost successful suicide. The nurses put me in a bed previously occupied by a young woman who hoarded her sleeping pills and died there three days earlier. The staff asked me if I needed any pills to help me sleep.

The absurdity was clarifying. I stayed in that Norwalk Hospital psyche ward for months – my parents were too afraid, too ashamed to visit, and left me to “experts” who visited for 10 minutes and lots of Nurse Ratched wanna-bes. I learned what I had to do to avoid shock “therapy” – smile, nod, lie, and not judge my fellow inmates.

When I finally got out, I gave up LSD and, having dropped out of college, I studied philosophy at Fairfield University. My brain kept pressing existential questions as if they were immediate and real. I took up the occult and hitchhiked to Alfred University in Upstate New York to study A.E. Russell, W.B. Yeats, and the Rosicrucians. I lived with a bunch of witches and warlocks with whom I drank beer and watched the original “Star Trek” broadcast from Canada – after which we smoked doobies and argued existential bullshit about each episode.

One guy in the house had dropped so much acid that he was stuck. He’d either wander around blank-eyed or jump on the furniture like a threatening chimp. I was glad I’d given up acid.

I didn’t get clean and sober until 1980 when my bosses at CBS News thought I’d make a good test project for their new Employee Assistance Program. The theory was: it’s easier and cheaper to sober up a good, screwed-up employee than to hire and train a new one. I balked. I had reasons. I had excuses. They didn’t understand. I’d stop on my own.

But I couldn’t stop, and they did understand. They gave me an ultimatum. Go to rehab or get fired. I thought of jobs where I could drink and use without hassle. But being a journalist had become my identity. Who would I be without that? Now that was an existential question.

I had two bad glasses of white wine and smoked a joint before I went to a rehab that June near the Amityville Horror House. But I’ve been clean and sober ever since.

It took me WAY LONGER to surrender my alcoholic arrogance, and even decades later in recovery, I still have bouts of depression, which I link to my dormant addiction. Today, I cherish life and my choices.

But with Rob and Michele Reiner’s murders, a rehab phrase has reappeared: “You know you’re getting better when you’re homicidal and not suicidal.”

I know this was intended metaphorically to help a suicide addict like me: first, a ludicrous smile; then accessing the long-oppressed anger, fear, and abandonment; then taking steps to get out of it. But recognizing that addiction kills is no laughing matter.

I do not know Nick Reiner. I met Rob Reiner through Chad Griffin and AFER. However, like so many others, I appreciated him “representing” hippies as caring progressives on “All in the Family.” He was similarly caring in real life, as evidenced by his humble, emotional reaction on Piers Morgan’s show, honoring Erika Kirk’s forgiveness of her husband Charlie Kirk’s assassin.

I do not know Nick’s story – I do not know the anguish of having schizophrenia and drug addiction. But I know in my heart his parents loved him to the moon and back. I suspect Romy and Jake and the Reiners’ friends are struggling not just with unimaginable grief but with how, in some way, to have compassion for this ill addict they loved who lived among them.

Perhaps this is an odd way to express gratitude to America’s greatest “good guy.” I hope by sharing my story, the spirits of Rob and Michele may realize they did everything they could – they did not fail their son. He, too, has individual freedom – including to make horrible wrong choices willingly, even those orchestrated by addiction. Or did mental illness combined with addiction strip him of that choice?

Forgiveness is not yet on the horizon. But perhaps a greater willingness for compassionate understanding can be.

And hopefully, by sharing these human frailties, those who are struggling will find the strength to defy stigma, fear, and addiction’s arrogance and reach out for help.

As for me, today, I humbly acknowledge: “There, but for the Grace of God, go I.”

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This essay was updated from the original posted on Karen’s LGBTQ+ Freedom Fighters Substack.

COMMENTARY

Dating during the holidays: Why cuffing season hits GBTQ men so hard

For GBTQ men, the holidays can be one of the loneliest times of the year. Seasonal depression ramps up, it gets darker earlier, it’s colder, and suddenly everyone around you seems to be coupling up

The holidays do something to us.

They pull at our hearts, our memories, our wounds, and our longing, all at the same time. And honestly? Dating during this season can feel like an emotional obstacle course.

For GBTQ men, the holidays can be one of the loneliest times of the year. Seasonal depression ramps up, it gets darker earlier, it’s colder, and suddenly everyone around you seems to be coupling up. It’s like the whole world collectively decided to jump into a cuddle puddle and forgot to send you the invitation.

And that’s why “cuffing season” is a real thing.

People want warmth. They want touch. They want a body next to them under the blankets while the rest of the world posts family photos with matching pajamas.

We want connection.

We want closeness.

We want someone to come home to when everything feels cold.

But here’s the deeper truth — especially for queer people: A lot of us didn’t grow up with magical holiday memories.

Many of us were rejected, or disowned, or made to feel “different,” and the holidays can bring all that trauma back like it’s happening in real time. While other families were singing carols, some of us were hiding in our rooms, praying no one would notice how “different” we were.

So now, as adults, having a partner during the holidays can feel like having a chosen family.

It feels safe.

It feels comforting.

It feels like someone finally picked you.

And there’s nothing wrong with wanting that. We all deserve love. We all deserve someone who makes us feel held.

But…

(you know there’s always a “but”)

We also have to ask ourselves:

Is this connection real? Or is it holiday loneliness wrapped in mistletoe?

Are we craving a partner, or are we craving comfort?

Does our heart need love? Or does it just need some warmth and self-compassion?

Because cuffing season relationships can be beautiful, but they can also be Band-Aids. Temporary. Convenient. Easy.

The real question is:

Do you want a partner for the holidays… or a partner for your life?

And if you’re single right now, as a matchmaker, I want to share something important:

You’re not behind.

You’re not failing.

You’re not missing some magical holiday checklist.

Being single during the holidays is not a punishment, even though it can feel like it when you’re sitting on your mom’s couch watching your siblings and cousins live out their Hallmark movie fantasy. Their husbands, their wives, their perfect kids, everyone in matching sweaters — and you’re like, “Cool, I’ll just be over here in the corner petting the dog.”

But disappearing into the extra bedroom and crying into a pillow isn’t your only option.

(Though if you need a five-minute cry, listen… you’re human.)

As a private matchmaker, here’s what I tell my clients — and myself! — every year:

1. You don’t need a partner to belong.

Chosen family is real. Friends are real. Community is real.

Sometimes your holiday joy comes from the people you choose, not the people you were born into.

2. You are allowed to create your own traditions.

A queer Christmas.

A gay Friendsgiving.

A holiday dinner with your spiritual family, your gym friends, your brunch crew, your book club.

Your joy isn’t limited to the house you grew up in.

3. Self-love is not a consolation prize.

It’s the thing that makes every relationship — including your future one — healthier.

4. The holidays aren’t a deadline.

Just because the world feels coupled doesn’t mean you have to rush into something just to survive December.

As a matchmaker, I see the other side too. And here’s what I want you to remember:

A lot of people do find love during cuffing season — real love, lasting love, beautiful love.

Because when loneliness rises, so does honesty. People open up more in the winter. They’re more vulnerable and willing to take a leap.

But whether you’re dating, single, complicated, or “it’s a long story,” know this:

You are not alone.

You are not behind.

And the holidays don’t define your worth.

If you end up in a relationship this season — amazing.

If you don’t — you still belong, you are still loved, and your story is still unfolding exactly how it’s supposed to.

And who knows…

Maybe next December, you’ll be the one cuddling up with someone who feels like home.

But for now?

Give yourself grace.

Give yourself compassion.

And give yourself permission to experience the holidays in the way that feels right for you.

You’re not broken.

You’re not missing anything.

You are enough today, this month, this season, all of it.

Daniel Cooley, LGBTQ+ Matchmaker & Co-owner of Best Man Matchmaking – California’s premier service for queer and trans men seeking emotional connections. Learn more here.

Join us at our Gay Singles Night on Thursday, December 3rd, at the Geffen Playhouse with LA Blade’s Matchmaker Daniel Cooley for an unforgettable evening! This evening includes a post-show talkback. Use code: LAB49T17 for $49 (includes per ticket fee) for Premium, Section A, or Section B seating. No ticket limit. No refunds or ticket exchanges. Visit geffenplayhouse.org to purchase your tickets. Code also valid for performances Dec.4-7, including weekend matinees.

Opinions

Mattachine Society in LA marks 75th anniversary

Seven gay men met in Edendale home on Nov. 11, 1950.

On Nov. 11, 1950, Veteran’s Day, seven homosexual men met in a home in what was then called the Edendale section of Los Angeles, now referred to as Echo Park. They came together, secretly, recruited by Harry Hay to found the Mattachine Society, the commencement of the long march to freedom by LGBTQ people in the United States. A statue needs be erected in L.A. to honor those seven men: Hay, Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, Rudi Gernreich, Dale Jennings, James Gruber, and Konrad Stevens.

I still get chills as I read the oath of initiation taken into the Mattachine that day to the sounds of Pachelbel’s “Canon” softly playing in the background, an oath eventually heard around the world: “We are sworn that no boy or girl, approaching the maelstrom of deviation, need to make that crossing alone, afraid and in the dark ever again.”

In that oath about the “boy or girl,” the word “deviation” reverberates through a thousand years in the West of hetero supremacy and enforced heterosexualism with all that implies. All LGBTQ people were once that “boy or girl.” Thus began a core principle of LGBTQ community — we assume responsibility for each other.

Nov. 11, 2025, marks the 75th anniversary of that moment. As far as my information at this time, as a gay elder, I’m embarrassed to report to those seven gay ancestors: not a single event is planned in L.A. to commemorate that historic date, just as L.A. Pride occurred in WeHo on the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion, the reason for Pride’s existence, without ever mentioning a word about Stonewall.

Why is that erasure of important LGBTQ history happening in L.A. and elsewhere? In previous articles in the LA Progressive, I have tried to explain that erasure by the Elite Capture of the LGBTQ community with top-down leadership, a total blackout of local news or investigative journalism, community members becoming spectators rather than participants, and new community moral values that reduce everyone to donors and consumers.

While a very short-lived effort was made in Chicago in the 1920s, which was quickly broken up by the police, the Mattachine represents the first successful attempt in the U.S. at organizing homosexual men and women. They used the oppressor’s word, “homosexual,” to describe themselves. After World War II, several of the men had been members of or had flirted with the U.S. Communist Party or were members of other progressive organizations, where they learned organizing skills, analysis of social problems, and secret organizing. It was that secret organizing, as necessary as it may have been, that became its Achilles’ Heel. Hay was kicked out of the CP by CP leader Gus Hall’s purge of known or suspected homosexual men and women after World War II.

The name “Mattachine” came from the word “matticini,” one of the names for jesters in royal courts of medieval Europe which Hay deduced from his research were homosexual men.

The Mattachine is important for more than just existing for three years (1950-1953). In its original organizing “manifesto,” written by Hay, for the first time in U.S. history, homosexuals identified themselves as an oppressed minority group. The document also declared that a hidden homosexual culture existed. Also, it implied that collective political action was needed. That collective political action eventually came from Mattachine’s grandchildren with the fire and fervor of the collective action of the Gay Liberation Revolution (1969-1985) — the Great Awakening. Will Roscoe’s “Radically Gay” will introduce you to this valuable historical written material of the Mattachine.

The Mattachine was a top-down organization based on a secret model of five levels that had been used by the Free Masons in 15th century Europe and later employed during World War II by the French Resistance. The original seven members were on level-five and newcomers on level one, not knowing who was on the levels above them. Such organization, it was felt then, was necessary due to the viciousness and life destroying consequences at that time by U.S. hetero supremacists if homosexual identity were ever made public. Until the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion and its aftermath, sane paranoia based on individual protection and survival characterized homosexual reality.

The Mattachine’s most important contribution then was the use of private discussion groups that gave gay men and lesbians, for the first time, an opportunity to talk with each other about their lives and how hetero oppression was directly impacting them. But these groups often met cautiously.

There was one discussion group in an apartment building in Hollywood that required members to arrive as fake male-female couples, the men wearing male attire and the women in dresses, lest the neighbors suspect that a homo group was meeting next door and alert the LAPD, who could soon be knocking on the door.

By late 1952-early 1953, it was reported that Mattachine had created almost a hundred discussion groups in California with about 2000 participants, a stunning achievement for the early 1950s. There were also Mattachine organizations happening in New York City; Washington, D.C.; San Francisco; and elsewhere. The discussion groups by then were taking on a more grassroots character with a wide range of people from various political proclivities and social classes, but, given the enforced racial segregation practiced in L.A. then, virtually all were white. There were whispers about their own publication.

Then, in March 1953, all hell broke loose when Paul Coates, a widely read newspaper columnist in the U.S., reported publicly for the first time the existence of the Mattachine in Los Angeles and the ties of some of its organizers to the Communist Party during the Red Scare period. I speculate that Coates was tipped off by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI who, after their first priority, the Red Scare, focused on their second priority, the Homo Scare.

The Mattachine was thrown into turmoil, not knowing whose outing was next, and the seven level-five men unmasked themselves.

At a meeting of the Mattachine at the First Unitarian Church, then on Crenshaw Boulevard, in the Spring of 1953, Hay and other founders resigned in the best interest of the organization, which was taken over by conservative Hal Call and moved to San Francisco, which is a sad story for another time. In my many dialogues with Hay about this period, he always referred disdainfully to the San Francisco group as the

“Second Mattachine,” to clearly differentiate it from the first.

Out of that chaos, in Los Angeles was formed ONE, Inc., which ushered in the conservative, Republican-led Homophile period (1953-1969), centered in Los Angeles, that recorded successes and failures which I have written about previously in the L.A. Progressive.

One essential way of understanding the Mattachine and Homophile periods is through the lens of the historiography of liberation movements. Both the Mattachine and Homophile years represented what is seen as “secondary resistance,” which involves the preparation of an oppressed people for liberation through discussion, writing, education, and some organizing of an elite nature. The “Big Bang” of the Gay Liberation Revolution was “primary resistance,” which involves direct action against the power of the oppressor, replaces it, and proactively creates a new sense of community free of the previous oppression. Or so they say.

One of my teachers, Malidoma Some, taught me about the importance of honoring ancestors as an essential ingredient of maintaining a healthy community. He also taught me about eldering. Among the Dagara people in Burkina Faso, from which he came and was an initiated shaman and initiated elder (also with two earned Ph.Ds. from the Paris Sorbonne University and Brandeis University), one of the important roles of elders was to scold the village for any shortcomings in fulfilling their responsibilities. Only elders had the authority to do that scolding.

As a Gay Tribal Elder, I send out a potential scold particularly to functioning and conscious LGBTQ adults and youth in the L.A. community. You are the boy or girl the Mattachine swore to protect. You are the great, great grandchildren of those pioneers. You have ancestor responsibilities. You might bring shame to a community by disregarding that important legacy. Being me, I also warmly say to you that you can always redeem yourselves. The 75th anniversary year of the Mattachine is just beginning on Nov. 11, the founding date in 1950. There is time during this coming year to be accountable in some notable way.

As the remarkable poet Kevin Young wrote recently, “the dead won’t let/us be.”

Don Kilhefner, Ph.D., has been a gay community organizer for the past 60 years in Los Angeles, nationally, and internationally.

COMMENTARY

Abandoned by the system: How CHLA turned its back on trans patients

Lu’s personal story captures the emotional and medical fallout of CHLA’s decision, exposing the broader issue of institutional retreat under political pressure.

Lu Orona recounts his experience beginning transition at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) — the same institution that recently announced it would no longer provide gender-affirming care, even to young adults who have relied on it for years.

When I was 17, I began my medical transition at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA). Getting there took more than a year of obstacles: endless referrals, canceled appointments, and being told again and again that “we don’t do that here.” CHLA became my first real opening, the place that finally treated me as someone who deserved care instead of as a problem to be managed.

Before that, I had lived in a body that never felt like mine. I didn’t know what safety or ease felt like until I began testosterone. A year later, CHLA approved me for top surgery. For the first time, I could breathe deeply without the weight of a binder or the heavier weight of a healthcare system that had long rejected me. It was the first time I felt whole.

At my first consultation, I was shaking, expecting another rejection. Instead, I was treated with dignity. The day I gave myself my first testosterone injection. I cried, not from fear, but from the overwhelming sense that I was finally allowed to exist as myself. It was the beginning of a freedom I had been told I’d never have.

In the months that followed, the suicidal thoughts that once defined my days began to quiet. For the first time, I felt alive rather than just enduring life. I could laugh with friends, feel the sun on my skin, and experience my body as my own. CHLA had become my anchor in a world that so often told me I didn’t belong.

Then, this summer, that lifeline was cut.

In July, CHLA announced it would stop providing gender-affirming care, not just for minors, but for young adults like me. At 23, after five years of consistent care, I was told that my treatment would end. The same hospital that once helped me feel safe had withdrawn that safety without warning.

The decision is cruel in its inconsistency: CHLA continues to offer hormones and surgeries to cisgender patients, yet those same treatments are now off-limits for trans people. The hospital’s public statement framed the change as a policy for minors, but I stand as living proof that young adults are also being abandoned, with consequences that are immediate and devastating.

Losing CHLA doesn’t simply mean finding another doctor. It means starting over in a healthcare maze filled with waitlists, insurance denials, and clinics that treat trans care as an afterthought. I’ve lived this before. When I lost access to testosterone due to an insurance gap, my body shifted rapidly, my periods returned, my hormonal balance collapsed, and my mental health deteriorated. It took half a year before I felt stable again.

This is not only about healthcare logistics. It’s about trust, and how fragile it becomes for people who already face discrimination at every level of the medical system. Trans people experience higher rates of anxiety, depression, and trauma precisely because our access to care is never guaranteed. When an institution like CHLA walks away, it reinforces a message that has haunted us for decades: our health is conditional, our lives negotiable.

Accountability must come now, not later. If one institution retreats, others have a moral duty to step forward. Leadership in healthcare cannot mean showing up for Pride Month and disappearing when controversy arises. It must mean sustained, public, and enforceable commitments to trans patients—commitments that do not bend under pressure. Symbolic support is no longer enough. What we need are permanent policies and protections that make our care non-negotiable.

This responsibility extends beyond hospitals. Lawmakers, insurers, and the public must recognize that gender-affirming care is not elective. It is evidence-based, essential, and for many of us, life-saving. When it is stripped away, people suffer and some will not survive. The impact reaches far beyond youth, affecting young adults like me who are left without options mid-treatment.

This moment cannot be allowed to fade into another headline. Each closure, each withdrawal of care, pushes trans people back into silence and despair. CHLA may have stepped away, but I will not disappear with it.

We deserve a future in which trans people do not merely survive but thrive. That future is not an abstraction; it is possible, and the fight for it begins now.

Lu’s op-ed was presented on behalf of the California LGBTQ+ HHS Network in honor of Transgender Awareness Week 2025

COMMENTARY

Uplifting small businesses uplifts us ALL

If we want to keep West Hollywood’s economy strong, we have to make sure our systems are helping, not hindering, the people who invest here.

By West Hollywood Councilmembers John M. Erickson and Danny Hang

When we ran for City Council, we both heard the same message repeatedly from residents and small business owners alike: it’s too hard to open a business in West Hollywood. From boutique owners on Santa Monica Boulevard to new café operators on the Eastside, people shared stories of navigating a complex maze of permits, design reviews, and approvals that can take months — sometimes more than a year — to complete. And if we are going to keep out the big box stores, create a steady revenue stream that helps fund our wonderful services, and protect our small-town charm, something needs to change.

That’s why we’ve coauthored a new policy initiative to streamline West Hollywood’s business permitting and signage regulations, making it faster, clearer, and more predictable for entrepreneurs to get up and running. This process in no way prevents community participation—it encourages it by putting people first.

Our small businesses are what make West Hollywood so special. They bring creativity, culture, and community to every block. But every month that a storefront sits empty or an opening is delayed costs jobs, tax revenue, and local vibrancy. If we want to keep West Hollywood’s economy strong, we have to make sure our systems are helping, not hindering, the people who invest here.

Cutting Red Tape, Not Corners

The City has already taken important steps through its Permitting Enhancement Initiatives, such as the Permit Navigator Program, which provides one-on-one support to guide business owners through the process, and the Over-the-Counter Plan Review, which allows low-impact projects to get same-day approval. These programs have helped, but it’s time to go further.

Our proposal directs City staff to take a comprehensive look at how we can streamline and modernize the entire permitting process, from tenant improvements to signage, and bring back recommendations to the City Council by Q1 2026 or as part of the next fiscal year’s work plan.

That review will include looking at how long it currently takes to open a new business, identifying where the delays are, and setting clear performance goals to measure progress. For example, we’re suggesting a target of getting 90 percent of new non-food businesses open within 120 days of application and food businesses within 180 days. These goals are ambitious but achievable, and they’ll give everyone a clear sense of accountability.

Updating Outdated Signage Rules

Another key part of this effort is updating West Hollywood’s sign ordinance. Our city has one of the most creative business communities in the country, yet many of our sign regulations were written decades ago and no longer reflect more effective, 21st-century norms for businesses to advertise and express their identity today.

We’re calling for staff to explore how signage rules can be modernized and streamlined, while still upholding West Hollywood’s design standards and visual character. That might mean allowing certain types of signs to be approved administratively rather than going through multiple rounds of review, clarifying what qualifies as a “creative sign,” and ensuring our rules keep pace with advances in technology and accessibility.

By making these updates, we can reduce unnecessary delays for business owners while still protecting what makes our city visually iconic.

Listening to Businesses, Measuring Success

This process will be collaborative. We’re directing staff to engage directly with the West Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, small business owners, local tenants, and neighborhood groups to ensure we’re identifying the right solutions and focusing on what matters most to those directly impacted. Again, this proposed process encourages robust community participation.

We’ll also ask for data (one of the most important tools we have at our disposal), a snapshot of recent permit applications, how long they took to process, and where improvements can be made. This transparency will create a baseline for tracking success over time, ensuring our efforts are grounded in results, not rhetoric.

Building on Our Progress

This initiative builds on the work of the Small Business Initiative Implementation Plan, adopted by the Council in 2023, which set out a roadmap to make West Hollywood more business-friendly (after all, we were named the most business-friendly city in 2021 by the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation). It also aligns with California’s AB 671, which now requires cities to expedite plan reviews for restaurant tenant improvements.

Together, these reforms will help ensure that West Hollywood continues to be a place where businesses — especially small, locally owned ones — can thrive.

Time for Swift Action

We’ve heard the feedback. We know the challenges. It’s time to act. Now.

Streamlining the permitting process isn’t just about efficiency; it’s about equity. Small business owners, especially first-time entrepreneurs and people from underrepresented communities, often don’t have the resources to navigate a slow and complicated system. By simplifying the process, we’re creating more opportunities for everyone.

When our local businesses succeed, our community thrives. We’re proud to bring forward this initiative, and we’re committed to working with our staff, local partners, and residents to make doing business in West Hollywood faster, clearer, and fairer for all.

John Erickson is a Councilmember and Former Mayor of the City of West Hollywood and a candidate for California State Senate District 24.

Danny Hang is a Councilmember of the City of West Hollywood and serves on the West Hollywood City Council Subcommittees for the Laurel House Project and Hart Park Phase II Improvements.

Commentary

Cities can’t improve the future with yesterday’s rules

California cities can’t keep building 21st-century infrastructure with 20th-century rules. It’s time to give local governments the flexibility to deliver for the people they serve.

Editor’s note: This piece is a follow-up to Councilmember Erickson’s August 12 op-ed, “Why California Must Remove the Roadblocks to Safer Streets,” in the Los Angeles Blade.

When I wrote earlier this year about why California must remove the roadblocks to safer streets, I focused on what local governments like West Hollywood can do to fix our own processes. At our October 20 Council meeting, I’m advancing a proposal that will streamline how we plan and deliver infrastructure projects to move traffic better and make our streets safer—without unnecessary delays.

But sadly, this proposal is just not enough. Local reform can only go so far, as California’s cities are bound by outdated state contracting laws that tie our hands, waste taxpayer money, and make it harder to deliver the improvements our residents deserve.

If we’re serious about making our communities safer, cleaner, and more sustainable, we need statewide reform of the Public Contract Code—and that means allowing every city and county to utilize a best value contracting method for public projects.

Modernizing How We Improve Infrastructure

Under current state law, most cities must award public works contracts based solely on the lowest bid. On paper, that sounds fair. In practice, it often means that the lowest price wins over the best qualified bid—leading to cost overruns, project delays, and endless change orders. It’s the government equivalent of buying the cheapest option first and paying more for it later.

Best value contracting flips that equation. It allows cities to weigh qualifications, experience, sustainability, and innovation—not just price—when selecting contractors. This approach has already been proven successful by counties, universities, and some charter cities. But most local governments in California don’t have permanent access to this tool.

That needs to change.

If cities like West Hollywood could permanently use best value contracting, we could deliver safer streets, park improvements, and infrastructure upgrades faster, more efficiently, and at lower cost to taxpayers.

Cutting Bureaucratic Bloat and Building Trust

Reforming the Public Contract Code to make best value contracting a statewide option would do more than save time and money—it would restore trust in government. Residents are frustrated by projects that take years to design and even longer to build. The truth is, much of that delay is built into the system itself: outdated rules that reward red tape over results.

By embracing a best value model, we’d reduce bureaucratic bloat, empower city staff to focus on outcomes, and give communities more transparency in how projects are delivered—with the best overall outcome. It’s smart, responsible government—and it’s long overdue.

From Local Action to Statewide Change

West Hollywood is doing its part. Our “Removing Infrastructure Roadblocks” policy will streamline local project timelines and prioritize safety. But real, lasting change requires partnership from Sacramento.

It’s time for the State Legislature to update the Public Contract Code and give every city the permanent ability to use best value contracting. With that change, we can finally build faster, smarter, and fairer—while saving money and lives along the way.

The path to safer streets starts in our cities, but the power to clear the roadblocks lies with the state. Let’s make it happen.

On Monday, October 20, the West Hollywood City Council will consider my proposal to remove local infrastructure roadblocks and set a new model for how cities can build more efficiently. I’m inviting everyone who believes in safer, smarter, and faster investment in our public spaces to show up and make your voice heard.

You can attend in person at the West Hollywood City Council Chambers (625 N. San Vicente Blvd.) or submit a public comment online at www.weho.org/agendas. Every voice matters — your input helps ensure we build a city and a state that works for everyone.

The path to safer streets starts here in West Hollywood. Let’s take that first step together — and let’s make sure California clears the roadblocks statewide.

California cities can’t keep building 21st-century infrastructure with 20th-century rules. It’s time to give local governments the flexibility to deliver for the people they serve.

John Erickson is a Councilmember and Former Mayor of the City of West Hollywood and a candidate for California State Senate District 24.

-

a&e features4 days ago

a&e features4 days agoMelvin Robert will perform homecoming solo at Gay Men’s Chorus of LA’s Spring concert

-

Events4 days ago

Events4 days agoCarrying the sapphic torch forward: The Dinah returns this year with new leaders

-

Theater1 day ago

Theater1 day agoAura Mayari discusses the glamorous fascism of ‘Here Lies Love’

-

Best of LGBTQ LA5 days ago

Best of LGBTQ LA5 days agoThe Los Angeles Blade’s Best of LA Awards Show returns for its 9th year

-

Movies5 days ago

Movies5 days agoIntense doc offers transcendent treatment of queer fetish pioneer

-

Commentary3 days ago

Commentary3 days agoThe fad of family estrangement: Ending connections in order to honor the ones that truly sustain us

-

Commentary2 days ago

Commentary2 days agoWhy Trump’s ‘Call to Duty’ Christian crusade against Iran matters in California’s gubernatorial race

-

Sports1 day ago

Sports1 day agoPride House LA/West Hollywood announces partnership with Angel City Football Club

-

Features3 hours ago

Features3 hours agoFrom brownstones to beachfronts: Jed Inductivo shares on his real estate journey