AIDS and HIV

Pioneering South African AIDS researcher Joseph Sonnabend dies at 88

Pioneering AIDS researcher and clinician Joseph Sonnabend, 88, died January 24, 2021

(Photo Credit: Simon Watney, Kent, UK via Facebook)

LONDON, UK – Pioneering AIDS researcher and clinician Joseph Sonnabend, 88, died January 24, 2021 at London’s famed Wellington Hospital after suffering a heart attack on January 3, 2021.

Born in Johannesburg, South Africa, to a physician mother and university professor father, Joseph Adolph Sonnabend grew up in Bulawayo, in what was then Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). He trained in infectious diseases at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh.

In the 1960s, Sonnabend worked in London under Alick Isaacs, the co-discoverer of interferon, at the National Institute of Medical Research. In the early 1970s, he moved to New York City to continue interferon research as associate professor at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine. Sonnabend later served as Director of Continuing Medical Education at the Bureau of VD Control at the New York City Department of Health, where he advocated for a focus on gay men’s health, particularly programs to reduce sexually-transmitted infections.

In 1978, he volunteered at the Gay Men’s Health Project in Sheridan Square, Greenwich Village, New York City and started a private clinic for treating sexually transmitted infections. When gay men in his practice began to get sick, he was among the first clinicians in the U.S. to recognize the emerging AIDS epidemic.

Sonnabend was widely respected as an unusually compassionate clinician and researcher, willing to see any patient regardless of ability to pay, never giving up on a patient and always providing hope. In return, he earned an unusually devoted appreciation and admiration from his patients.

Simon Watney, a writer, activist and close friend of Sonnabend’s, said, “One of Joe’s most important contributions was his belief—that he conveyed to his patients—that AIDS would not be 100% fatal, that no matter how bleak the prognosis, some people would ultimately survive. That provided powerful hope at a time when hope was in short supply.”

In a POZ Magazine interview in 1998, Sonnabend said,

“I realize that I was seeing cases of AIDS-related PCP in the late ’70s. But I first encountered the disease a few months before the first New York Times report in July 1981. I had a patient who had parasites and had become anemic. And in order to have him worked up for anemia I referred him to a colleague. She had him admitted to St. Vincent’s Hospital. In the course of working up his anemia, they put a tube down his stomach and saw these purple lesions. The biopsy showed Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS). Well, neither of us knew much about this rare a cancer, so she called the National Cancer Institute for a referral, and found out that there were 26 or 28 cases of young homosexual men in New York with KS. And this was unbelievable.”

With a background in microbiology, virology, infectious diseases, and experience working with immune-compromised transplant patients, Sonnabend was uniquely qualified to help the scientific community grasp a better understanding this new, pernicious disease. Working independently of government agencies, which were slow to respond to the epidemic in those early days, Sonnabend conducted some of earliest research into AIDS, often at his own expense.

“The other doctors who were treating AIDS didn’t have the research experience or the instincts or the colleagues. I’m not putting them down. They were just doctors with patients. And the academic researchers—the top immunologists, virologists and so on—who had the expertise, didn’t have the patients. I had both the background and the patients. And that was an amazing discovery. I mean, it was as if I had jewels. I had something so valuable. I had patients who liked me, who were willing to give me blood, who would participate in anything. The one thing I didn’t have was a freezer. I couldn’t afford a freezer, so I kept the blood in a refrigerator that had a little freezing compartment.”

To purchase a freezer and help fund research on his patients—before HIV was discovered or the disease had a name—Sonnabend reached out to a former interferon colleague, Dr. Mathilde Krim, who was also a noted philanthropist and fundraiser. He asked Krim to help raise $10,000; that collaboration led Sonnabend, Krim, activist Michael Callen and others to found the AIDS Medical Foundation, the first AIDS research group, now known as amfAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research.

Sonnabend resigned as chair of amfAR’s Scientific Advisory Committee in 1985, protesting what he believed was the organization’s over-hyping, for fundraising purposes, of the threat of heterosexual female to male HIV transmission.

When asked about Sonnabend’s contributions to the epidemic in 1998, Krim said, “What did Sonnabend contribute? He contributed me. He was the one who alerted me to the problem. I remember the day in the early ’80s when Joe came to me and said, ‘I’ve lost my stature as a physician. I have patients with big lymph nodes and high fevers, and they don’t get better. What’s strange is they’re all young, gay men.’ He’s the only doctor I know who goes to every funeral. From the beginning, Joe said the government was wrong to give money to academic clinical research—people who had no contact with the disease.”

Sonnabend also pioneered community-based clinical research, helping to launch the Community Research Initiative (now ACRIA) and other organizations. In 1983 he founded and until 1986 edited the journal AIDS Research, the first professional peer-reviewed publication focused on the epidemic. With Michael Callen and Tom Hannan, he co-founded the PWA Health Group, the first “buyers club” for people with AIDS in the world.

From the earliest days of the epidemic, Sonnabend championed the rights of people living with AIDS. He was particularly concerned by the ethical issues around the AIDS crisis, winning the Nellie Westerman Prize for Research in Ethics with his co-authors in 1983 for the article “Confidentiality, Informed Consent and Untoward Social Consequences in Research on a ‘New Killer Disease’ (AIDS)” in the journal Clinical Research. His work inspired the New York State Legislature to pass the first confidentiality protections for people with AIDS. In 1984, he initiated, with five of his patients and the New York State Attorney General, the first AIDS-related civil rights litigation, suing his landlord for attempting to evict him for treating people with AIDS at his office.

Believing that patients are their own best advocates, Sonnabend encouraged his patients to speak for themselves, not to rely on government officials, LGBT community leaders or others. When he introduced two of his patients, Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz, it launched an historic activist collaboration. With Sonnabend’s groundbreaking scientific guidance and editing, Callen and Berkowitz introduced the concept of “Safer Sex” to a global audience, through their landmark booklet, “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach”.

When Sonnabend found the use of Bactrim was effective as prophylaxis against pneumocystis carnii pneumonia, the leading killer of people with AIDS in the 80s, he urged his patients and community activists to advocate with government officials and educate community clinicians to establish Bactrim prophylaxis as a standard of care, saving an untold number of lives.

David Kirschenbaum, an AIDS activist and close friend, said “When thinking of all his accomplishments and contributions to saving lives during the AIDS crisis, one cannot separate Joe the scientist/physician from Joe the man. His compassion for humanity was the driving force behind all that he was able to achieve in medical research. This is why he eschewed the spotlight which he so rightly deserves.”

Sonnabend earned the ire of some gay community activists when he encouraged gay men to change their sexual behaviors to avoid sexually-transmitted diseases, rather than just to have fewer sexual partners, as advocated by Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the leading AIDS service provider in New York at the time.

Prior to the identification of HIV as the cause of AIDS in 1984, Sonnabend’s investigations led him to propose that AIDS among gay men might be caused by multiple factors, including Epstein-Barr virus and repeated exposure to cytomegalovirus and semen. His multi-factorial model conflicted with the view that a single agent was likely responsible, which Sonnabend did not rule out. After the discovery of HIV, he acknowledged that HIV alone was enough to cause AIDS, but he maintained that repeated assaults on one’s immune system from sexually-transmitted diseases played a role in the progression and severity of HIV infection.

“When AIDS first appeared, having witnessed this incredible surge in STDs in the late ’70s, I felt that the two were connected. Saying that it was caused by some brand-new virus just didn’t seem reasonable to me. I had been trained in a view of health and disease that had gone out of fashion by the time this disease hit. In my day, we were taught to look at disease not simply as something caused by a germ—there are many other factors that affect one’s immunity and the ability to handle infectious diseases.”

Reflecting on his multi-factorial model in 1998, Sonnabend said,

“In the beginning, as far as gay men were concerned, I thought this disease was only affecting those with a history of multiple STDs. But now I’ve encountered people who apparently have never had syphilis, hepatitis or anything else—who don’t fit into that model. So that was wrong. The other thing is the role of HIV. It’s not as simple as saying that HIV causes AIDS. It’s rather a view that infection with almost any microorganism doesn’t cause disease in every infected person. It’s not clear that HIV came from monkeys who suddenly started to bite people in the last hundred years. It’s probably been endemic for ages in a small percentage of humans, maybe more or less in different geographic areas. And that a small inoculum may not be followed by seroconversion, but that HIV becomes integrated into DNA, dormant and latent. It may be reactivated, but the immune system may control it and not enough virus is made to seroconvert. After all, many species have their own immunodeficiency retrovirus, which usually doesn’t cause disease. Why should humans be any different? I don’t think we’re dealing with a simple infectious disease.”

In 2000, he was recognized as an inaugural Award of Courage Honoree by amfAR. In 2005, he retired from his medical practice in New York and moved to London and on World AIDS Day that year, he was awarded a Red Ribbon Leadership Award from the National HIV/AIDS Partnership. In 2018, at the age of 85, he made his public debut as a composer of classical music, with a concert at London’s Fitzrovia Chapel, part of the AIDS Histories and Cultural Festival.

Sean Strub, POZ magazine’s founder and a former patient, wrote in a 1998 profile of Sonnabend, “The environment (in his office) was such that patients in the waiting room sometimes rearranged the order of seeing Joe, based on our collective assessment of who needed to see him first, or who had other doctors’ appointments to get to. Joe’s patients are protective of him. Those of us with insurance remind him to send out bills; those without often helped in his office, cooked him dinner or volunteered with the organizations Joe started. Over the years, his patients have redecorated, filed, cleaned and helped in the management of his practice.”

He was pre-deceased by his sister, Yolanda Sonnabend, the renowned theatre designer and artist. He is survived by close friends, former colleagues, a number of his patients and two sons. Funeral details and a memorial event will be announced at a later date.

AIDS and HIV

Local organization aims to support and assist Black LGBTQ+ community

REACH LA is stepping up their mission amid hostile administration

REACH LA, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit organization aimed at working with youth of color, is stepping up their prevention resources during Black History Month to support the LGBTQ+ community of color.

Though today is National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, REACH LA works year-round to provide resources to their community members.

This month, the organization is amplifying its mission to support Black LGBTQ+ youth by offering free HIV testing and care throughout February, offering a $25 gift card as incentive to get tested. This and all of REACH LA’s efforts are geared toward assisting the marginalized Black and Latin American communities by reducing stigma, increasing education and assisting community members with resources.

The QTBIPOC community is especially vulnerable to political and personal attacks. As we head into the next four years under a hostile administration whose goal is to erase queer and trans people, there will be continued attacks on federal funding and on any other front possible.

“This year, it is especially vital, more than ever, to amplify and commemorate National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day. At REACH LA, we are currently engaging with individuals and partnerships while navigating through dire and uncertain times where HIV/AIDS awareness prevention efforts, access, and visibility have been under attack and restricted,” said Jeremiah Givens, chief marketing and communications officer at REACH LA.

It is important to spotlight the intersection between health equity, Black LGBTQ+ empowerment and community-based solutions during Black History Month and every other month throughout the year and especially during this particularly vulnerable time.

As one of eight CDC PACT Program Partners, REACH LA celebrates National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day with a Positive Living Campaign in collaboration with the CDC’s Let’s Stop HIV Together initiative. The campaign highlights the resilience of individuals living with HIV and works to raise awareness and foster community support.

To learn more about resources, visit their website or stop in for testing, support and other resources. The organization’s doors are open Monday through Friday, from 11 AM to 7 PM for free, on-site HIV testing and assistance with accessing PREP and PEP, linkage to care and free mental health therapy.

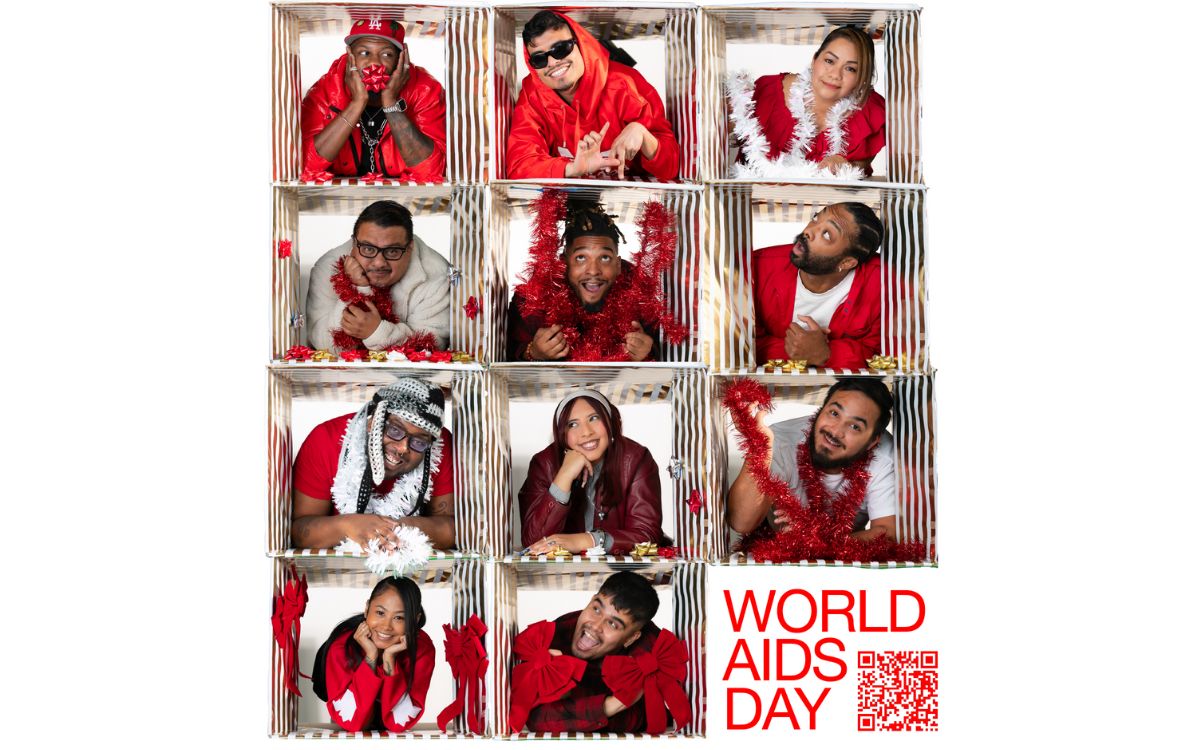

Over 300 people gathered last Monday to commemorate World AIDS Day in an event hosted by Bienestar Human Services. The non-profit focuses on identifying and addressing emerging health issues faced by Latinx and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans Queer and more (LGBTQ+) populations.

The main objective of the annual event was to light a candle to honor those who passed away due to Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and celebrate those who, despite the condition, keep going.

HIV is the virus that causes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Once you have HIV, the virus stays in the body for life, and while there is no cure. There is, however, medicine that can help people stay healthy, states Planned Parenthood. HIV destroys the cells that protect the human body from infections. If a person doesn’t have enough of these CD4 or T cells, the body can’t fight off infections as normal. This damage can lead to AIDS, which is the most serious stage of HIV, and it leads to death over time.

In the U.S., there are about 1.3 million people newly infected with HIV in 2023 and 39.9 million living with HIV, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

Living with HIV for decades

Among the participants at the event at the Ukrainian Culture Center on Melrose in East Hollywood was Marcela, a transgender woman who was diagnosed HIV positive 33 years ago. She said when she learned about her diagnosis, she was so depressed she tried to commit suicide. She ended up at the hospital, and after getting better, she heard about an organization that was helping people with health issues such as hers.

“Since then, I learned to live with this condition because it is not an illness; it’s a condition,” she said.

Bienestar celebrated the World AIDS Day on December 2, 2024. (Courtesy of Bienestar)

Marcela, who didn’t provide her last name, said she not only found a new way of living with HIV but also found an extended family at Bienestar. They have guided her on how to receive the proper treatment and medicines, to be part of a support group and even to pay her rent when she needed it the most.

The 64-year-old woman doesn’t have any family members in the United States. She said five years ago, her husband passed away of pneumonia. She was living alone in Long Beach and got behind her payments during the pandemic. She said Bienestar helped her apply for a grant of over $20,000 that secured the payment for her rent, and now she is debt-free.

“I’m extremely grateful to them and all the help they provide,” she said.

Working for the community

This year, Bienestar is celebrating 35 years of serving the LGBTQ+ community. Among the many programs they offer is the Support Group for Transgender Women, which Marcela belongs to.

Mia Perez, the support group manager, said 15 to 20 members attend the group every Friday from 3 to 5 p.m. They talk about their feelings, share experiences, and plan and participate in social events.

Perez said one of the participants’ biggest concerns is accepting reality once they have been diagnosed. “However, with all these new treatments people that are HIV positive can have a normal relationship with someone who doesn’t have HIV. It’s all about getting informed,” said Perez.

Other concerns include what will happen to them once the new presidential administration takes office since they have plans to deport immigrants and many of the transgender women are immigrants.

“That’s why we are trying to get in contact with an immigration attorney or an organization so they can keep them informed of their rights,” said Perez.

Bienestar events, like World AIDS Day, help those affected create a stronger community, and they realize the recognition is not just for those who are HIV positive but also for their families and friends.

Marcela said when she is feeling down or bored at home, all she has to do is go to Bienestar and the people there always give her a warm welcome.

“They give me coffee, they offer me lunch. Being there is like being at home,” she said.

AIDS and HIV

New monument in West Hollywood will honor lives lost to AIDS

In 1985, WeHo sponsored one of the first awareness campaigns in the country, nationally and globally becoming a model city for the response to the epidemic

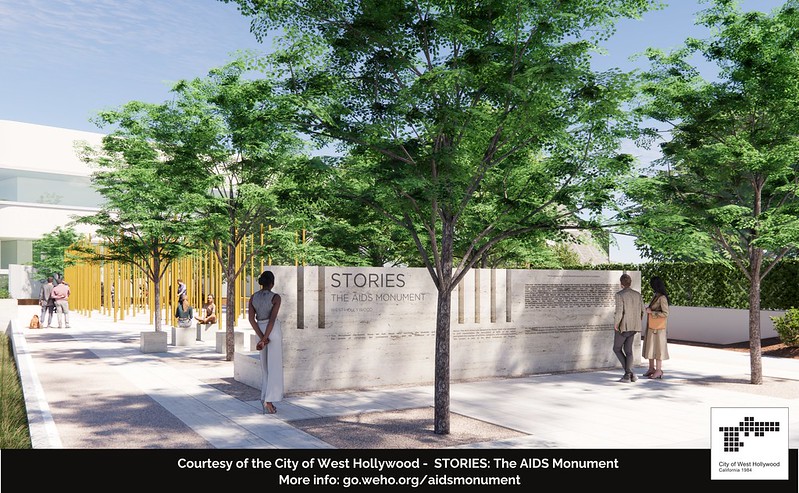

December is AIDS/HIV awareness month and this year West Hollywood is honoring the lives lost, by breaking ground on a project in West Hollywood Park that has been in the works since 2012.

Members of Hollywood’s City Council joined representatives from the Foundation of AIDS Monument to announce the commencement of the construction of STORIES: The AIDS Monument, which will memorialize 32 million lives lost. This monument, created by artist Daniel Tobin, will represent the rich history of Los Angeles where many of those afflicted with HIV/AIDS lived out their final days in support of their community.

Tobin is a co-founder and creative director of Urban Art Projects, which creates public art programs that humanize cities by embedding creativity into local communities.

The motto for the monument is posted on the website announcing the project.

“The AIDS Monument:

REMEMBERS those we lost, those who survived, the protests and vigils, the caregivers.

CELEBRATES those who step up when others step away.

EDUCATES future generations through lessons learned.”

The monument will feature a plaza with a donor wall, vertical bronze ‘traces’ with narrative text, integrated lighting resembling a candlelight vigil, and a podium facing North San Vicente Blvd.

World AIDS Day, which just passed, is on December 1st since the World Health Organization declared it an international day for global health in 1988 to honor the lives lost to HIV/AIDS.

The Foundation for the AIDS monument aims to chronicle the epidemic to be preserved for younger generations to learn the history and memorialize the voices that arose during this time.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic particularly affected people in Hollywood during the onset of the epidemic in the 1980s. The epidemic caused a devastatingly high number of deaths in the city. The city then became one of the first government entities to provide social service grants to local AIDS and HIV organizations.

In 1985, the city sponsored one of the first awareness campaigns in the country, nationally and globally becoming a model city for the response to the epidemic.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released the theme for World AIDS Day, ‘Collective Action: Sustain and Accelerate HIV Progress.’

The city of West Hollywood continues to strive to become a HIV Zero city with its current implementation of HIV Zero Initiative. The initiative embraces a vision to “Get to Zero” on many fronts: zero new infections, zero progression of HIV to AIDS, zero discrimination and zero stigma.

Along with the initiative and the new AIDS monument, the city also provides ongoing support and programming through events for World AIDS Day and the annual AIDS Memorial Walk in partnership with the Alliance for Housing and Healing.

For more information, please visit www.weho.org/services/human-services/hiv-aids-resources.

AIDS and HIV

National Latino AIDS Awareness Day: Breaking down stigma, silence and silos

FLAS provides HIV and STD education

When Elia Chino, Founder and Executive Director of the Fundacion Latinoamericana De Acción Social (FLAS) Inc., initially approached major HIV/AIDS agencies in Houston, Texas for support in starting an organization tailored specifically to reaching Latino populations, she was met with confusion.

“Why do you want to start a separate organization?” they asked. “We’re here!”

Chino remembers her frustration. “They didn’t understand,” she said. “Our brothers and sisters were dying, and the community needed services that they couldn’t provide.”

Indeed, in the 1990s, barriers to HIV care and treatment for Latino populations were markedly different from those faced by other populations. Information about the HIV epidemic was largely in English, and inaccessible to many individuals who had immigrated from indigenous Latin American communities and never learned to read and write in their native language, let alone English. When they were able to access treatment, Latino individuals often faced mistreatment at primary care facilities due to a lack of culturally competent care.

Perhaps most challenging was the culture of silence. Many Latino immigrants living with HIV in the United States fled homophobia, transphobia and stigma in their home countries, and were still grappling with lasting shame and guilt. Despite many people dying, there was little open discussion or education about the cause. In fact, Chino didn’t even know that the HIV epidemic took the lives of some of her best friends until speaking with their families years later.

“No one was talking about their diagnosis,” says Chino. “People had come to the United States for freedom, but still weren’t ready to talk about who they were. There was a real atmosphere of stigma, taboo, misinformation and fear.”

At the time, Chino was volunteering at a hospital serving communities without insurance. The fourth, fifth and sixth floors were all dedicated to treating people with HIV. Chino began educating herself on this crisis while she volunteered at the hospital, and founded FLAS in 1994 after discovering that the majority of HIV prevention efforts were not reaching Latino individuals.

In the beginning, without support from other organizations in the area or resources to expand, Chino was a one-woman show, conducting outreach in clubs, cantinas and bars by herself. She hadn’t anticipated the barriers she’d face as a member of the LGBTQ+ community and an immigrant. Horrible discrimination, a language barrier and intense HIV stigma in the communities she was working in made the work challenging, but also emphasized the necessity of what she was doing.

Over time, with support and funding from organizations like Gilead Sciences, FLAS has been able to expand its services from solely HIV prevention to include HIV testing, behavioral health services, housing and social services assistance, support groups and a food pantry. The organization has started hosting educational events everywhere from churches to street corners, raising awareness about HIV in the Houston community. Chino also started collaborating with the consulate of Mexico to help newcomers navigate U.S. health systems and services when they arrive in the United States. Next year, the organization will start offering mobile HIV testing clinics for communities in need.

Since its launch, FLAS has been able to expand its initial focus to address the holistic drivers of this crisis, moving beyond medical determinants of health to tackle the social and structural barriers that perpetuate the HIV epidemic and prevent Latino populations from accessing comprehensive treatment.

“Everyone keeps telling Latino individuals to get tested, but this does nothing unless you actually incentivize people to do so,” says Chino. “People have to go to work. They have to pay their rent. They have to buy food. Many can’t afford to lose their salary and spend a full day coming in to do a test or get treatment. We have to make it easier to access HIV prevention and treatment, and we have to provide incentives.”

This year marked FLAS’s 30th anniversary, which the organization celebrated with a gala in August. They have made a huge impact in Houston since their launch – providing HIV and STD education to over 500,000 Latino people, distributing over 20,000 HIV tests, referring over 40,000 people for social services and hosting over 6,000 educational events and health fairs in English and Spanish. However, many of the challenges for HIV prevention and treatment for Latino populations remain.

“We have over 30,000 individuals living with HIV in Houston, yet when we ask for people to talk about their status, no one comes forward to tell their stories. HIV is a chronic disease, but stigmatization is still so strong in the Latino community,” says Chino. “You can say you have cancer, high blood pressure, diabetes, whatever – but nobody says I have HIV. There is still so much work to do.”

As a testament to their important programming, FLAS is a recipient of funding through Gilead Sciences’ TRANScend® Community Impact Fund, a program aimed at empowering Trans-led organizations working to improve the safety, health and wellness of the Transgender community. Since its inception in 2019, TRANScend has awarded more than $9.2 million in grants to 26 community organizations across 15 U.S. states and territories.

TRANScend support has been critical to helping FLAS maintain its services. In 2020, in the midst of the COVID pandemic, Gilead’s funding helped FLAS continue to offer virtual behavioral and mental health services to the community when their physical offices had to close.

According to Chino, this type of partnership is critical to ending the HIV epidemic in Latino communities, especially for meeting communities where they are.

“Communities trust their grassroots organizations, and grassroots organizations provide for their communities,” she says. “At the end of the day, we need to continue to support the groups doing the difficult work on the ground with the people they’re serving, especially those breaking down stigma and lasting barriers to care for Latino communities.”

AIDS and HIV

40th anniversary AIDS Walk happening this weekend in West Hollywood

AIDS Project Los Angeles Health will gather in West Hollywood Park to kick off 40th anniversary celebration

APLA Health will celebrate its 40th anniversary this Sunday at West Hollywood Park, by kicking off the world’s first and oldest AIDS walk with a special appearance by Salina Estitties, live entertainment, and speeches.

APLA Health, which was formerly known as AIDS Project Los Angeles, serves the underserved LGBTQ+ communities of Los Angeles by providing them with resources.

“We are steadfast in our efforts to end the HIV epidemic in our lifetime. Through the use of tools like PrEP and PEP, the science of ‘undetectable equals intransmissible,’ and our working to ensure broad access to LGTBQ+ empowering healthcare, we can make a real step forward in the fight to end this disease,” said APLA Health’s chief executive officer, Craig E. Thompson.

For 40 years, APLA Health has spearheaded programs, facilitated healthcare check-ups and provided other essential services to nearly 20,000 members of the LGBTQ+ community annually in Los Angeles, regardless of their ability to pay.

APLA Health provides LGBTQ+ primary care, dental care, behavioral healthcare, HIV specialty care, and other support services for housing and nutritional needs.

The AIDS Walk will begin at 10AM and registrations are open for teams and solo walkers. More information can be found on the APLA Health’s website.

AIDS and HIV

Cautious Optimism in San Francisco as New Cases of HIV in Latinos Decrease

The decrease could mark the first time in five years that Latinos haven’t accounted for the largest number of new cases

SAN FRANCISCO — For years, Latinos represented the biggest share of new HIV cases in this city, but testing data suggests the tide may be turning.

The number of Latinos newly testing positive for HIV dropped 46% from 2022 to 2023, according to a preliminary report released in July by the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

The decrease could mark the first time in five years that Latinos haven’t accounted for the largest number of new cases, leading to cautious optimism that the millions of dollars the city has spent to remedy the troubling disparity is working. But outreach workers and health care providers say that work still needs to be done to prevent, and to test, for HIV, especially among new immigrants.

“I am very hopeful, but that doesn’t mean that we’re going to let up in any way on our efforts,” said Stephanie Cohen, who is the medical director of the city’s HIV and STI prevention division.

Public health experts said the city’s latest report could be encouraging, but that more data is needed to know whether San Francisco has addressed inequities in its HIV services. For instance, it’s still unclear how many Latinos were tested or if the number of Latinos exposed to the virus had also fallen — key health metrics the public health department declined to provide to KFF Health News. Testing rates are also below pre-pandemic levels, according to the city.

“If there are fewer Latinos being reached by testing efforts despite a need, that points to a serious challenge to addressing HIV,” said Lindsey Dawson, the associate director of HIV Policy and director of LGBTQ Health Policy at KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

San Francisco, like the rest of the country, suffers major disparities in diagnosis rates for Latinos and people of color. Outreach workers say that recent immigrants are more vulnerable to infectious diseases because they don’t know where to get tested or have a hard time navigating the health care system.

In 2022, Latinos represented 44% of new HIV cases in San Francisco, even though they accounted for only 15% of the population. Latinos’ share of new cases fell to 30% last year, while whites accounted for the largest share of new cases at 36%, according to the new report.

Cohen acknowledged a one-year decline is not enough to draw a trend, but she said targeted funding to community-based organizations may have helped lower HIV cases among Latinos. A final report is expected in the fall.

Most cities primarily depend on federal dollars to pay for HIV services, but San Francisco has an ambitious target to be the first U.S. city to eliminate HIV, and roughly half of its $44 million HIV/AIDS budget last year came from city coffers. By comparison, New Orleans, which has similar HIV rates, kicked in only $22,000 of its $13 million overall HIV/AIDS budget, according to that city’s health department.

As part of an effort to address HIV disparities among LGBTQ+ communities and people of color, San Francisco last year gave $2.1 million to three nonprofits — Instituto Familiar de la Raza, Mission Neighborhood Health Center, and San Francisco AIDS Foundation — to bolster outreach, testing, and treatment among Latinos, according to the city’s 2023 budget.

At Instituto Familiar de la Raza, which administers the contract, the funding has helped pay for HIV testing, prevention, treatment, outreach events, counseling, and immigration legal services, said Claudia Cabrera-Lara, director of the HIV program at Sí a la Vida. But ongoing funding isn’t guaranteed.

“We live with the anxiety of not knowing what is going to happen,” she said.

The public health department has commissioned a $150,000 project with Instituto Familiar de la Raza to determine how Latinos are contracting HIV, who is most at risk, and what health gaps remain. The results are expected in September.

“It could help us shape, pivot, and grow our programs in a way that makes them as effective as possible,” Cohen said.

The center of the HIV epidemic in the mid-1980s, San Francisco set a national model for response to the disease after building a network of HIV services for residents to get free or low-cost HIV testing, as well as treatment, regardless of health insurance or immigration status.

Although city testing data showed that new cases among Latinos declined last year, outreach workers are seeing the opposite. They say they are encountering more Latinos diagnosed with HIV while they struggle to get out information about testing and prevention — such as taking preventive medications like PrEP — especially among the young and gay immigrant communities.

San Francisco’s 2022 epidemiological data shows that 95 of the 213 people diagnosed at an advanced stage of the virus were foreign-born. And the diagnosis rate among Latino men was four times as high as the rate for white men, and 1.2 times that of Black men.

“It’s a tragedy,” said Carina Marquez, associate professor of medicine in the Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases, and Global Medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, the city’s largest provider of HIV care. “We have such great tools to prevent HIV and to treat HIV, but we are seeing this big disparity.”

Because Latinos are the ethnicity least likely to receive care in San Francisco, outreach workers want the city to increase funding to continue to reduce HIV disparities.

The San Francisco AIDS Foundation, for instance, would like more bilingual sexual health outreach workers; it currently has four, to cover areas where Latinos have recently settled, said Jorge Zepeda, its director of Latine Health Services.

At Mission Neighborhood Health Center, which runs Clinica Esperanza, one of the largest providers of HIV care to Latinos and immigrants, the number of patients seeking treatment has jumped from about two a month to around 16 a month.

Among the challenges is getting patients connected to mental health and substance abuse bilingual services crucial to retaining them in HIV care, said Luis Carlos Ruiz Perez, the clinic’s HIV medical case manager. The clinic wants to advertise its testing and treatment services more but lacks the money.

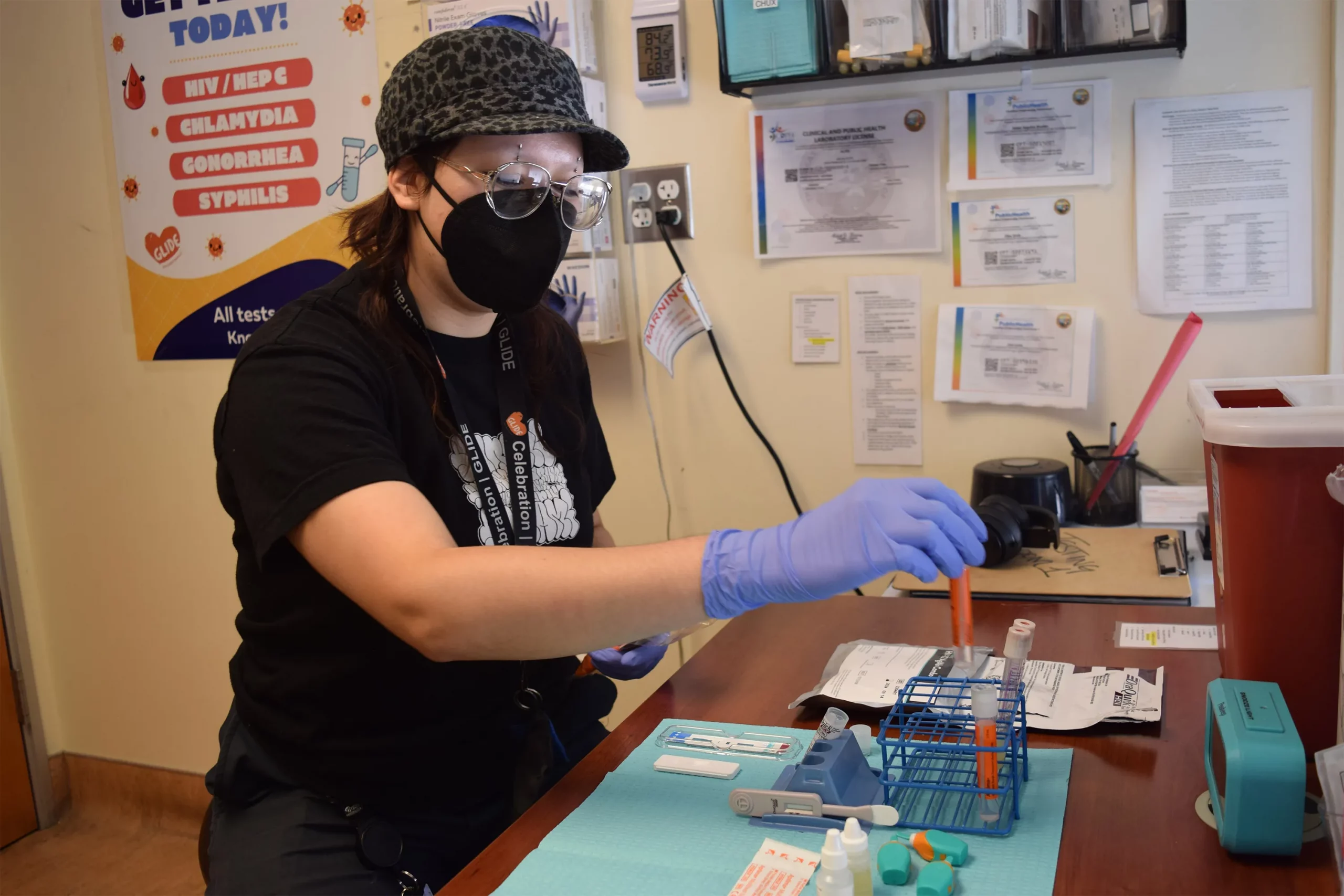

“A lot of people don’t know what resources are available. Period,” said Liz Oates, a health systems navigator from Glide Foundation, who works on HIV prevention and testing. “So where do you start when nobody’s engaging you?”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

AIDS and HIV

White House urged to expand PrEP coverage for injectable form

HIV/AIDS service organizations made call on Wednesday

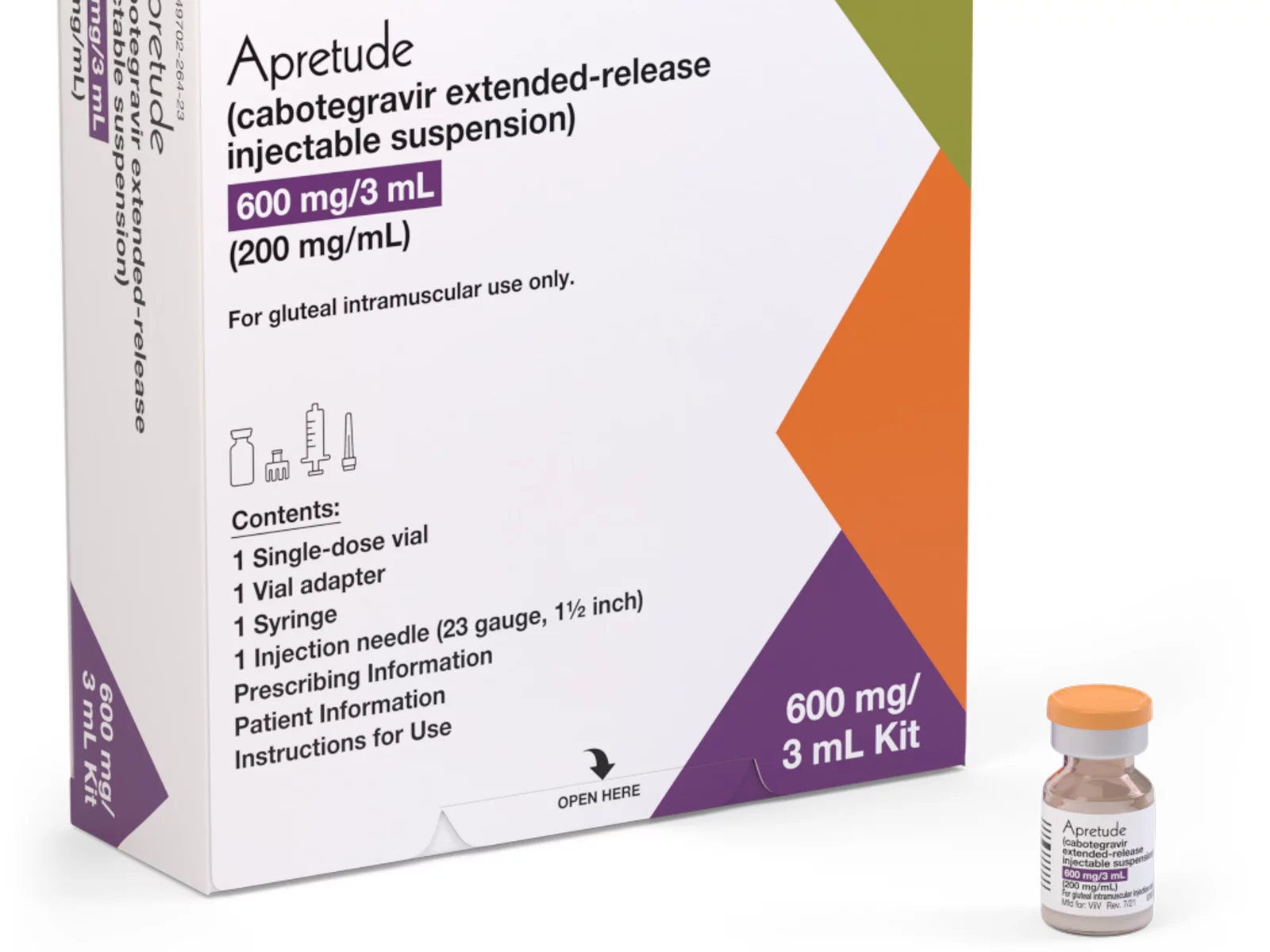

A coalition of 63 organizations dedicated to ending HIV called on the Biden-Harris administration on Wednesday to require insurers to cover long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) without cost-sharing.

In a letter to Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the groups emphasized the need for broad and equitable access to PrEP free of insurance barriers.

Long-acting PrEP is an injectable form of PrEP that’s effective over a long period of time. The FDA approved Apretude (cabotegravir extended-release injectable suspension) as the first and only long-acting injectable PrEP in late 2021. It’s intended for adults and adolescents weighing at least 77 lbs. who are at risk for HIV through sex.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendation for PrEP on Aug. 22, 2023, to include new medications such as the first long-acting PrEP drug. The coalition wants CMS to issue guidance requiring insurers to cover all forms of PrEP, including current and future FDA-approved drugs.

“Long-acting PrEP can be the answer to low PrEP uptake, particularly in communities not using PrEP today,” said Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute. “The Biden administration has an opportunity to ensure that people with private insurance can access PrEP now and into the future, free of any cost-sharing, with properly worded guidance to insurers.”

Currently, only 36 percent of those who could benefit from PrEP are using it. Significant disparities exist among racial and ethnic groups. Black people constitute 39 percent of new HIV diagnoses but only 14 percent of PrEP users, while Latinos represent 31 percent of new diagnoses but only 18 percent of PrEP users. In contrast, white people represent 24 percent of HIV diagnoses but 64 percent of PrEP users.

The groups also want CMS to prohibit insurers from employing prior authorization for PrEP, citing it as a significant barrier to access. Several states, including New York and California, already prohibit prior authorization for PrEP.

Modeling conducted for HIV+Hep, based on clinical trials of a once every 2-month injection, suggests that 87 percent more HIV cases would be averted compared to daily oral PrEP, with $4.25 billion in averted healthcare costs over 10 years.

Despite guidance issued to insurers in July 2021, PrEP users continue to report being charged cost-sharing for both the drug and ancillary services. A recent review of claims data found that 36 percent of PrEP users were charged for their drugs, and even 31 percent of those using generic PrEP faced cost-sharing.

The coalition’s letter follows a more detailed communication sent by HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute to the Biden administration on July 2.

Signatories to the community letter include Advocates for Youth, AIDS United, Equality California, Fenway Health, Human Rights Campaign, and the National Coalition of STD Directors, among others.

AIDS and HIV

Tennessee Agrees To Remove Sex Workers With HIV From Sex Offender Registry

The Tennessee government has agreed to begin scrubbing its sex offender registry of dozens of people who were convicted of prostitution while having HIV, reversing a practice that federal lawsuits have challenged as draconian and discriminatory.

For more than three decades, Tennessee’s “aggravated prostitution” laws have made prostitution a misdemeanor for most sex workers but a felony for those who are HIV-positive. Tennessee toughened penalties in 2010 by reclassifying prostitution with HIV as a “violent sexual offense” with a lifetime registration as a sex offender — even if protection is used.

At least 83 people are believed to be on Tennessee’s sex offender registry solely because of these laws, with most living in the Memphis area, where undercover police officers and prosecutors most often invoked the statute, commonly against Black and transgender women, according to a lawsuit filed last year by the American Civil Liberties Union and four women who were convicted of aggravated prostitution. The Department of Justice challenged the law in a separate suit earlier this year.

Both lawsuits argue that Tennessee law does not account for evolving science on the transmission of HIV or precautions that prevent its spread, like use of condoms. Both lawsuits also argue that labeling a person as a sex offender because of HIV unfairly limits where they can live and work and stops them from being alone with grandchildren or minor relatives.

“Tennessee’s Aggravated Prostitution statute is the only law in the nation that treats people living with HIV who engage in any sex work, even risk-free encounters, as ‘violent sex offenders’ subjected to lifetime registration,” the ACLU lawsuit states.

“That individuals living with HIV are treated so differently can only be understood as a remnant of the profoundly prejudiced early response to the AIDS epidemic.”

In a settlement agreement signed by Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee on July 15 and filed in both lawsuits on July 17, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation said it would comb through the state’s sex offender registry to find those added solely because of aggravated prostitution convictions, then send letters alerting those people that they can make a written request to be removed. The language of the settlement suggests that people will need to request their removal from the registry, but the agency said in the agreement it will make “its best effort” to act on the requests “promptly in the order in which they are received.”

The Tennessee attorney general’s office, which represents the state in both the ACLU and DOJ lawsuits and approved the settlement agreement, said in an email statement it would “continue to defend Tennessee’s prohibition on aggravated prostitution.”

In an email statement, the ACLU celebrated the settlement as “one step toward remedying the harms by addressing the sex offender registration,” but said its work in Tennessee was not done because aggravated prostitution remained a felony charge that it would “fight to overturn.”

Molly Quinn, executive director of LGBTQ+ support organization OUTMemphis, another plaintiff in the ACLU lawsuit, said both organizations would help eligible people with the paperwork to get removed from the registry.

“We would not have agreed to settle if we did not feel like this was a process that would be extremely beneficial,” Quinn said. “But, we’re sad that the statute existed as long as it did and sad that there is any process at all that folks have to go through after living with this extraordinary burden of being on the sex offender registry for really an irrelevant reason.”

Michelle Anderson, a Memphis resident who is one of the plaintiffs in the ACLU lawsuit, said in court records that since being convicted of aggravated prostitution, the sex offender label has made it so difficult to find a home and a job that she was “unhoused for about a year” and has at times “felt she had no option but to continue to engage in sex work to survive.”

Like the other plaintiffs, Anderson said her conviction kept her minor relatives at a distance.

“Ms. Anderson has a nephew she loves, but she cannot have a close relationship with him,” the lawsuit states. “Even though Ms. Anderson’s convictions had nothing to do with children, she cannot legally be alone with her nephew.”

The Tennessee settlement comes months after state lawmakers softened the law so no one else should be added to the sex offender registry for aggravated prostitution. Lawmakers removed the registration requirement and made convictions eligible for expungement if the defendant testifies they were a victim of human trafficking.

State Sen. Page Walley (R-Savannah), who supported the original aggravated prostitution law passed in 1991 and co-sponsored the recent bill to amend it, said on the floor of the legislature that the changes do not prevent prosecutors from charging people with a felony for aggravated prostitution. Instead, he said, the amendments undo the 2010 law that put those who are convicted on the registry “along with pedophiles and rapists for a lifetime, with no recourse for removal.”

“Having stood, as I mentioned, in 1991 and passed this,” Walley said, “it is a particular gratifying moment for me to see how we continue to evolve and seek what’s just and what’s right and what’s best.”

KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

AIDS and HIV

Young gay Latinos see rising share of new HIV cases, leading to call for targeted funding

Fernando Hermida diagnosed four months after asking for asylum

Four months after seeking asylum in the U.S., Fernando Hermida began coughing and feeling tired. He thought it was a cold. Then sores appeared in his groin and he would soak his bed with sweat. He took a test.

On New Year’s Day 2022, at age 31, Hermida learned he had HIV.

“I thought I was going to die,” he said, recalling how a chill washed over him as he reviewed his results. He struggled to navigate a new, convoluted health care system. Through an HIV organization he found online, he received a list of medical providers to call in D.C., where he was at the time, but they didn’t return his calls for weeks. Hermida, who speaks only Spanish, didn’t know where to turn.

By the time of Hermida’s diagnosis, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services was about three years into a federal initiative to end the nation’s HIV epidemic by pumping hundreds of millions of dollars annually into certain states, counties, and U.S. territories with the highest infection rates. The goal was to reach the estimated 1.2 million people living with HIV, including some who don’t know they have the disease.

Overall, estimated new HIV infection rates declined 23 percent from 2012 to 2022. But a KFF Health News-Associated Press analysis found the rate has not fallen for Latinos as much as it has for other racial and ethnic groups.

While African Americans continue to have the highest HIV rates in the U.S. overall, Latinos made up the largest share of new HIV diagnoses and infections among gay and bisexual men in 2022, per the most recent data available, compared with other racial and ethnic groups. Latinos, who make up about 19 percent of the U.S. population, accounted for about 33 percent of new HIV infections, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The analysis found Latinos are experiencing a disproportionate number of new infections and diagnoses across the U.S., with diagnosis rates highest in the Southeast. Public health officials in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, and Shelby County, Tennessee, where data shows diagnosis rates have gone up among Latinos, told KFF Health News and the AP that they either don’t have specific plans to address HIV in this population or that plans are still in the works. Even in well-resourced places like San Francisco, HIV diagnosis rates grew among Latinos in the last few years while falling among other racial and ethnic groups despite the county’s goals to reduce infections among Latinos.

“HIV disparities are not inevitable,” Robyn Neblett Fanfair, director of the CDC’s Division of HIV Prevention, said in a statement. She noted the systemic, cultural, and economic inequities — such as racism, language differences, and medical mistrust.

And though the CDC provides some funds for minority groups, Latino health policy advocates want HHS to declare a public health emergency in hopes of directing more money to Latino communities, saying current efforts aren’t enough.

“Our invisibility is no longer tolerable,” said Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, co-chair of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS.

Lost without an interpreter

Hermida suspects he contracted the virus while he was in an open relationship with a male partner before he came to the U.S. In late January 2022, months after his symptoms started, he went to a clinic in New York City that a friend had helped him find to finally get treatment for HIV.

Too sick to care for himself alone, Hermida eventually moved to Charlotte to be closer to family and in hopes of receiving more consistent health care. He enrolled in an Amity Medical Group clinic that receives funding from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, a federal safety-net plan that serves over half of those in the nation diagnosed with HIV, regardless of their citizenship status.

His HIV became undetectable after he was connected with case managers. But over time, communication with the clinic grew less frequent, he said, and he didn’t get regular interpretation help during visits with his English-speaking doctor. An Amity Medical Group representative confirmed Hermida was a client but didn’t answer questions about his experience at the clinic.

Hermida said he had a hard time filling out paperwork to stay enrolled in the Ryan White program, and when his eligibility expired in September 2023, he couldn’t get his medication.

He left the clinic and enrolled in a health plan through the Affordable Care Act marketplace. But Hermida didn’t realize the insurer required him to pay for a share of his HIV treatment.

In January, the Lyft driver received a $1,275 bill for his antiretroviral — the equivalent of 120 rides, he said. He paid the bill with a coupon he found online. In April, he got a second bill he couldn’t afford.

For two weeks, he stopped taking the medication that keeps the virus undetectable and intransmissible.

“Estoy que colapso,” he said. I’m falling apart. “Tengo que vivir para pagar la medicación.” I have to live to pay for my medication.

One way to prevent HIV is preexposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, which is regularly taken to reduce the risk of getting HIV through sex or intravenous drug use. It was approved by the federal government in 2012 but the uptake has not been even across racial and ethnic groups: CDC data show much lower rates of PrEP coverage among Latinos than among white Americans.

Epidemiologists say high PrEP use and consistent access to treatment are necessary to build community-level resistance.

Carlos Saldana, an infectious disease specialist and former medical adviser for Georgia’s health department, helped identify five clusters of rapid HIV transmission involving about 40 gay Latinos and men who have sex with men from February 2021 to June 2022. Many people in the cluster told researchers they had not taken PrEP and struggled to understand the health care system.

They experienced other barriers, too, Saldana said, including lack of transportation and fear of deportation if they sought treatment.

Latino health policy advocates want the federal government to redistribute funding for HIV prevention, including testing and access to PrEP. Of the nearly $30 billion in federal money that went toward things like HIV health care services, treatment, and prevention in 2022, only 4% went to prevention, according to a KFF analysis.

They suggest more money could help reach Latino communities through efforts like faith-based outreach at churches, testing at clubs on Latin nights, and training bilingual HIV testers.

Latino rates going up

Congress has appropriated $2.3 billion over five years to the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative, and jurisdictions that get the money are to invest 25 percent of it in community-based organizations. But the initiative lacks requirements to target any particular groups, including Latinos, leaving it up to the cities, counties, and states to come up with specific strategies.

In 34 of the 57 areas getting the money, cases are going the wrong way: Diagnosis rates among Latinos increased from 2019 to 2022 while declining for other racial and ethnic groups, the KFF Health News-AP analysis found.

Starting Aug. 1, state and local health departments will have to provide annual spending reports on funding in places that account for 30 percent or more of HIV diagnoses, the CDC said. Previously, it had been required for only a small number of states.

In some states and counties, initiative funding has not been enough to cover the needs of Latinos.

South Carolina, which saw rates nearly double for Latinos from 2012-2022, hasn’t expanded HIV mobile testing in rural areas, where the need is high among Latinos, said Tony Price, HIV program manager in the state health department. South Carolina can pay for only four community health workers focused on HIV outreach — and not all of them are bilingual.

In Shelby County, Tennessee, home to Memphis, the Latino HIV diagnosis rate rose 86 percent from 2012 to 2022. The health department said it got $2 million in initiative funding in 2023 and while the county plan acknowledges that Latinos are a target group, department director Michelle Taylor said: “There are no specific campaigns just among Latino people.”

Up to now, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, didn’t include specific targets to address HIV in the Latino population — where rates of new diagnoses more than doubled in a decade but fell slightly among other racial and ethnic groups. The health department has used funding for bilingual marketing campaigns and awareness about PrEP.

Moving for medicine

When it was time to pack up and move to Hermida’s third city in two years, his fiancé, who is taking PrEP, suggested seeking care in Orlando, Fla.

The couple, who were friends in high school in Venezuela, had some family and friends in Florida, and they had heard about Pineapple Healthcare, a nonprofit primary care clinic dedicated to supporting Latinos living with HIV.

The clinic is housed in a medical office south of downtown Orlando. Inside, the mostly Latino staff is dressed in pineapple-print turquoise shirts, and Spanish, not English, is most commonly heard in appointment rooms and hallways.

“At the core of it, if the organization is not led by and for people of color, then we’re just an afterthought,” said Andres Acosta Ardila, the community outreach director at Pineapple Healthcare, who was diagnosed with HIV in 2013.

“¿Te mudaste reciente, ya por fin?” asked nurse practitioner Eliza Otero. Did you finally move? She started treating Hermida while he still lived in Charlotte. “Hace un mes que no nos vemos.” It’s been a month since we last saw each other.

They still need to work on lowering his cholesterol and blood pressure, she told him. Though his viral load remains high, Otero said it should improve with regular, consistent care.

Pineapple Healthcare, which doesn’t receive initiative money, offers full-scope primary care to mostly Latino males. Hermida gets his HIV medication at no cost there because the clinic is part of a federal drug discount program.

The clinic is in many ways an oasis. The new diagnosis rate for Latinos in Orange County, Florida, which includes Orlando, rose by about a third from 2012 through 2022, while dropping by a third for others. Florida has the third-largest Latino population in the U.S., and had the seventh-highest rate of new HIV diagnoses among Latinos in the nation in 2022.

Hermida, whose asylum case is pending, never imagined getting medication would be so difficult, he said during the 500-mile drive from North Carolina to Florida. After hotel rooms, jobs lost, and family goodbyes, he is hopeful his search for consistent HIV treatment — which has come to define his life the past two years — can finally come to an end.

“Soy un nómada a la fuerza, pero bueno, como me comenta mi prometido y mis familiares, yo tengo que estar donde me den buenos servicios médicos,” he said. I’m forced to be a nomad, but like my family and my fiancé say, I have to be where I can get good medical services.

That’s the priority, he said. “Esa es la prioridad ahora.”

KFF Health News and The Associated Press analyzed data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the number of new HIV diagnoses and infections among Americans ages 13 and older at the local, state, and national levels. This story primarily uses incidence rate data — estimates of new infections — at the national level and diagnosis rate data at the state and county level.

Bose reported from Orlando, Fla.. Reese reported from Sacramento, Calif. AP video journalist Laura Bargfeld contributed to this report.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is responsible for all content.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

A Project of KFF Health News and the Associated Press co-published by Univision Noticias

CREDITS:

Reporters: Vanessa G. Sánchez, Devna Bose, Phillip Reese

Cinematography: Laura Bargfeld

Photography: Laura Bargfeld, Phelan M. Ebenhack

Video Editing: Federica Narancio, Kathy Young, Esther Poveda

Additional Video: Federica Narancio, Esther Poveda

Web Production: Eric Harkleroad, Lydia Zuraw

Special thanks to Lindsey Dawson

Editors: Judy Lin, Erica Hunzinger

Data Editor: Holly Hacker

Social Media: Patricia Vélez, Federica Narancio, Esther Poveda, Carolina Astuya, Natalia Bravo, Juan Pablo Vargas, Kyle Viterbo, Sophia Eppolito, Hannah Norman, Chaseedaw Giles, Tarena Lofton

Translation: Paula Andalo

Copy Editing: Gabe Brison-Trezise

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

AIDS and HIV

Researchers announce using gene editing tool, HIV cut out of cells

The team eliminated HIV from cells in a laboratory raising hopes of a cure, but cautioned that for now their work represents proof of concept

BARCELONA, Spain – Researchers from the Amsterdam University Medical Center made a groundbreaking announcement this week of the results of a major study to be presented at the 2024 European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, which will be held April 27-30 in Barcelona.

A team led by Dr. Elena Herrera-Carrillo using a gene-editing tool known as Crispr-Cas, were able to eliminate HIV DNA, removing all traces of the virus from infected cells. In the press release Tuesday, Dr. Herrera-Carrillo alongside team members Yuanling Bao, Zhenghao Yu and Pascal Kroon, said that utilizing the gene-editing tool they focused on parts of the virus that stay the same across all known HIV strains.

“These findings represent a pivotal advancement towards designing a cure strategy,” the team said.

Herrera-Carrillo’s team works in developing a cure for HIV infection based on novel CRISPR-Cas methods. CRISPR-Cas is a powerful gene editing tool working like genetic scissors but can also be used to selectively attack and inactivate integrated HIV DNA genomes in infected cells.

Herrera-Carrillo’s team eliminated HIV from cells in a laboratory, raising hopes of a cure, but cautioned that for now their work represents proof of concept, and will not become a cure for HIV tomorrow. According to the researchers the next steps involve optimizing the delivery route to target the majority of the HIV reservoir cells within the body.

The hope the research team points out, is to devise a strategy to make this system as safe as possible for future clinical applications, and achieve the right balance between efficacy and safety. “Only then can we consider clinical trials of ‘cure’ in humans to disable the HIV reservoir,” they stated adding, “While these preliminary findings are very encouraging, it is premature to declare that there is a functional HIV cure on the horizon.”

-

Theater5 days ago

Theater5 days agoGeffen Playhouse’s The Reservoir finds queer humor and joy in recovery and loss

-

COMMENTARY3 days ago

COMMENTARY3 days agoUSAID’s demise: America’s global betrayal of trust

-

a&e features4 days ago

a&e features4 days agoHow this Texas drag king reclaimed their identity through Chicano-inspired drag

-

Obituary3 days ago

Obituary3 days agoThe queer community mourns the loss of trailblazer Jewel Thais-Williams

-

Television2 days ago

Television2 days agoICYMI: ‘Overcompensating’ a surprisingly sweet queer treat

-

a&e features5 days ago

a&e features5 days agoFrom Drag Race to Dvořák: Thorgy Thor takes the Hollywood Bowl for Classical Pride

-

Arts & Entertainment4 days ago

Arts & Entertainment4 days agoMary Lambert Returns With a Battle Cry in new single, “The Tempest”

-

Opinions23 hours ago

Opinions23 hours agoThe psychology of a queer Trump supporter: Navigating identity, ideology, and internal conflict

-

Living21 hours ago

Living21 hours agoFaithfully queer: Finding God and growth in Modern Orthodoxy

-

Breaking News9 hours ago

Breaking News9 hours agoTrump administration sues California over trans student-athletes