Books

A fascinating tale of Paris and literature in early 20th century

If you love books and sexual freedom you’ll adore ‘The Paris Bookseller’

‘The Paris Bookseller’

By Kerri Maher

c. 2022, Berkley

$26/336 pages

In LGBTQ bars, men dance with men and women kiss women. In artistic neighborhoods, straight people dine and drink with their queer friends. Queer couples and throuples are among the leaders of the avant-garde. Yet, there’s some repression. Books are banned.

You might think such goings-on can only be found in a present-day gayborhood or cultural hotspot.

But, this isn’t just a 21-century tableau. It was the scene a century ago in Paris where queer and hetero artists and writers, flirting, dancing, making art, drinking, dining and partying together, created some of the most acclaimed writing of the 20th century.

At the center of it all was Sylvia Beach and her bookshop Shakespeare and Company.

“The Paris Bookseller,” a new novel by Kerri Maher, brings us into the creative, diverting world of Paris from 1917 to 1936. Many titans of modernist art and literature thrived there (often before they were famous) – from Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas to Ernest Hemingway to Ezra Pound to Andre Gide to Paul Valery to James Joyce. Some were French. Others were American, British, Irish, or Canadian expats.

Sylvia Beach, a bookish American lesbian, who loved Paris, writers, books, and especially, her bookshop, was the friend, librarian, sometimes publisher, hand-holder – den mother – of this community.

Maher has given readers a fab work of historical fiction. Much has been written about Joyce, Stein, Hemingway and their gang. But comparatively little has been written about Beach, who lived from 1887 to 1962.

Beach lived openly for years with her lover and business partner Adrienne Monnier, and published Joyce’s groundbreaking novel “Ulysses,” which had run into censorship.

“The Bookseller” is a fascinating tale of the day-to-day life of Shakespeare and Company, the cultural hub, that nurtured the post-World War I generation of writers and artists.

Told from Beach’s point of view, the novel brings us inside Beach’s solar plexus as she delights in cafes and literary readings; strokes Joyce’s cranky ego and, later, with Monnier, faces the economic hardships of the Depression.

Beach was born in Baltimore. Her father was a Presbyterian minister and her mother supported women’s suffrage. Beach had two sisters – Holly and Cyprian, an actress who was also a lesbian.

In 1901, Beach moved with her family to Paris when her father was appointed assistant minister of the American Church in Paris. She lived in Princeton, N.J., for a time when her father was a minister there.

She then lived in Spain and worked for the Red Cross’ Balkan Commission of the Red Cross. As a volunteer in World War I, she did arduous farm work in Touraine, France.

But Paris had captured Beach’s heart. “Nothing compared to Paris,” Beach thought on her return to the City of Light, “not knocking on doors with Cyprian and Holly and Mother for the National Woman’s Party in New York; not her first longed-for kiss with her classmate Gemma Bradford; not winning the praise of her favorite teachers.”

If you like novels that make your heart pound with tension every nano-sec, “The Paris Bookseller” may not be the book for you. There are no severed heads. Gertrude Stein takes a few digs at Beach. There’s some snark. Monnier and Beach privately refer to Joyce as the “crooked Jesus” because he can be so annoying. But no knives are taken out.

Yet, “The Paris Bookseller” in its cozy, elegant way has more than its share of drama. It feels relatable to today – when increasing numbers of books are being banned.

Because being gay has been decriminalized in France since the French Revolution, LGBTQ people could live openly in post World War I Paris.

Yet there was a backlash against this freedom.

“Ulysses” was banned because it was thought to be obscene. Against this backdrop, a century ago, on Feb. 2, 1922, Beach published “Ulysses.”

Maher deftly engulfs us in the exaltation, joy, pain, and financial difficulties that Beach endured in dealing with Joyce and publishing his masterpiece.

If you love Paris, cafes, books, difficult geniuses, sexual freedom and censorship battles, you’ll adore “The Paris Bookseller.”

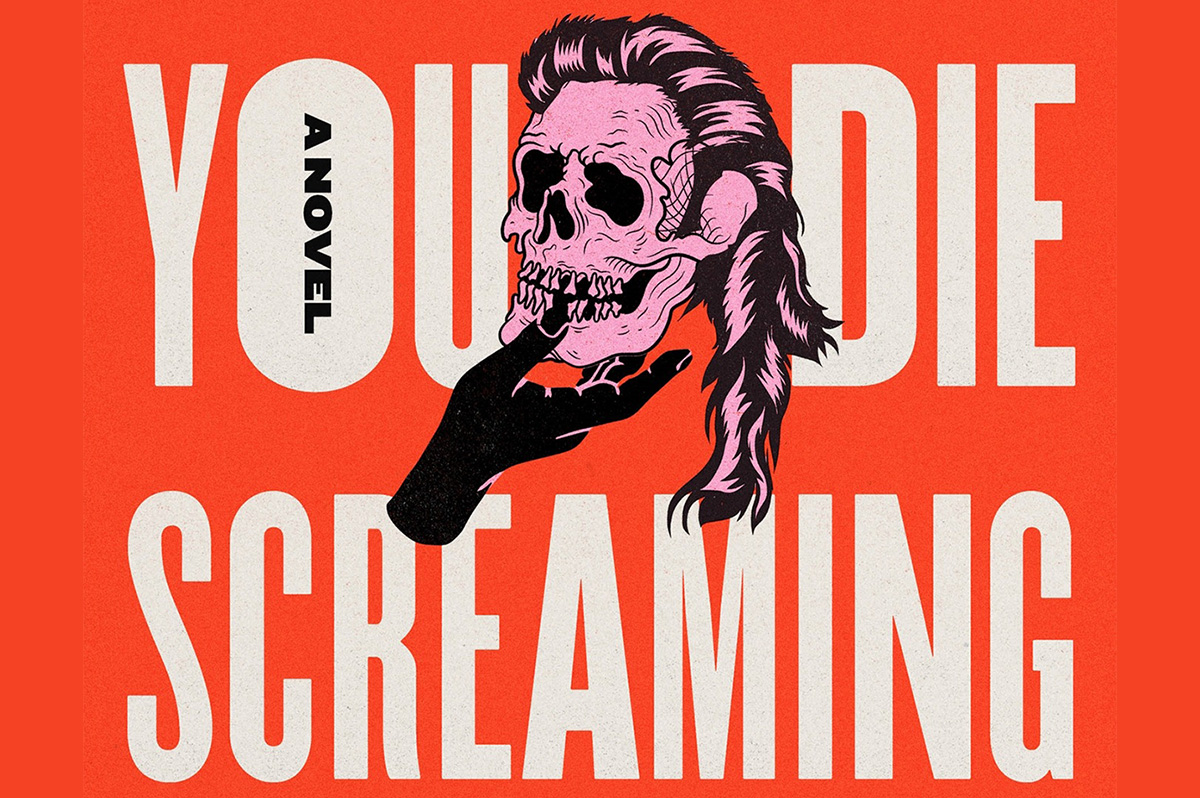

Books

Embracing the chaos can be part of the fun

‘Make Sure You Die Screaming’ offers many twists and turns

‘Make Sure You Die Screaming’

By Zee Carlstrom

c.2025, Random House

$28/304 pages

Sometimes, you just want to shut the door and forget what’s on the other side.

You could just wipe it from your memory, like it didn’t occur. Or create an alternate universe where bad things never happen to you and where, as in the new novel “Make Sure You Die Screaming” by Zee Carlstrom, you can pretend not to care.

Their mother called them “Holden,” but they’d stopped using that name and they hadn’t decided what to use now. What do you call an alcoholic, queer, pessimistic former ad executive who’s also “The World’s First Honest White Man,” although they no longer identify as a man? It’s a conundrum that they’ll have to figure out soon because a cop’s been following them almost since they left Chicago with Yivi, their psychic new best friend.

Until yesterday, they’d been sleeping on a futon in some lady’s basement, drinking whatever Yivi mixed, and trying not to think about Jenny. They killed Jenny, they’re sure of it. And that’s one reason why it’s prudent to freak out about the cop.

The other reason is that the car they’re driving was stolen from their ex-boyfriend who probably doesn’t know it’s gone yet.

This road trip wasn’t exactly well-planned. Their mother called, saying they were needed in Arkansas to find their father, who’d gone missing so, against their better judgment, they packed as much alcohol as Yivi could find and headed south. Their dad had always been unique, a cruel man, abusive, intractable; he suffered from PTSD, and probably another half-dozen acronyms, the doctors were never sure. They didn’t want to find him, but their mother called…

It was probably for the best; Yivi claimed that a drug dealer was chasing her, and leaving Chicago seemed like a good thing.

They wanted a drink more than anything. Except maybe not more than they wanted to escape thoughts of their old life, of Jenny and her death. And the more miles that passed, the closer they came to the end of the road.

If you think there’s a real possibility that “Make Sure You Die Screaming” might run off the rails a time or three, you’re right. It’s really out there, but not always in a bad way. Reading it, in fact, is like squatting down in a wet, stinky alley just after the trash collector has come: it’s filthy, dank, and profanity-filled. Then again, it’s also absurd and dark and philosophical, highly enjoyable but also satisfying and a little disturbing; Palahniuk-like but less metaphoric.

That’s a stew that works and author Zee Carlstrom stirs it well, with characters who are sardonic and witty while fighting the feeling that they’re unredeemable losers – which they’re not, and that becomes obvious.

You’ll see that all the way to one of the weirdest endings ever.

Readers who can withstand this book’s utter confusion by remembering that chaos is half the point will enjoy taking the road trip inside “Make Sure You Die Screaming.”

Just buckle up tight. Then shut the door, and read.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

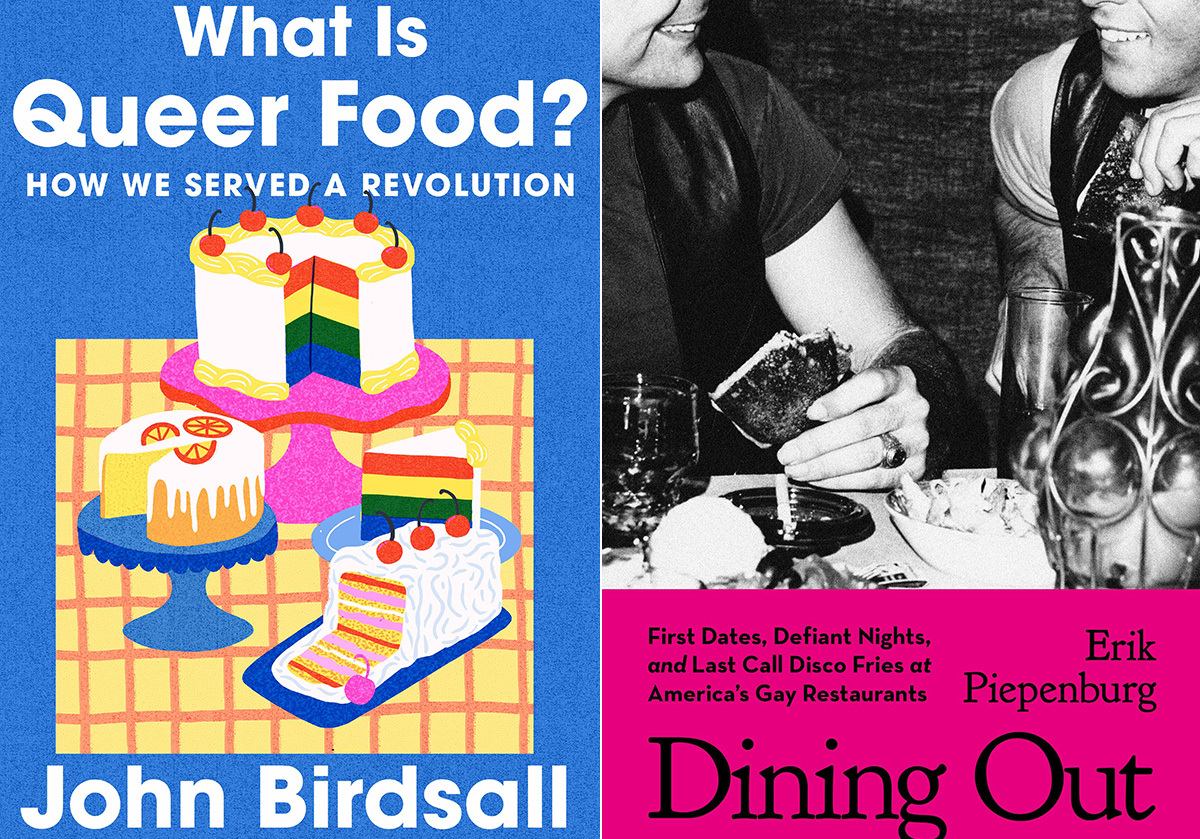

Books

Two new books on dining out LGBTQ-style

Visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers

‘What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution’

By John Birdsall

c.2025, W.W. Norton

$29.99/304 pages

‘Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants’

By Erik Piepenburg

c.2025, Grand Central

$30/352 pages

You thought a long time about who sits where.

Compatibility is key for a good dinner party, so place cards were the first consideration; you have at least one left-hander on your guest list, and you figured his comfort into your seating chart. You want the conversation to flow, which is music to your ears. And you did a good job but, as you’ll see with these two great books on dining LGBTQ-style, it’s sometimes not who sits where, but whose recipes were used.

When you first pick up “What is Queer Food?” by John Birdsall, you might miss the subtitle: “How We Served a Revolution.” It’s that second part that’s important.

Starting with a basic gay and lesbian history of America, Birdsall shows how influential and (in)famous 20th century queer folk set aside the cruelty and discrimination they received, in order to live their lives. They couldn’t speak about those things, he says, but they “sat down together” and they ate.

That suggested “a queer common purpose,” says Birdsall. “This is how who we are, dahling, This is how we feed our own. This is how we stay alive.”

Readers who love to cook, bake or entertain, collect cookbooks, or use a fork will want this book. Its stories are nicely served, they’re addicting, and they may send you in search of cookbooks you didn’t know existed.

Sometimes, though, you don’t want to be stuck in the kitchen, you want someone else to bring the grub. “Dining Out” by Erik Piepenburg is an often-nostalgic, lively look at LGBTQ-friendly places to grab a meal – both now and in the past.

In his introduction, Piepenburg admits that he’s a journalist, “not a historian or an academic,” which colors this book, but not negatively. Indeed, his journeys to “gay restaurants” – even his generous and wide-ranging definitions of the term – happily influence how he presents his narrative about eateries and other establishments that have fed protesters, nourished budding romances, and offered audacious inclusion.

Here, there are modern tales of drag lunches and lesbian-friendly automats that offered “cheap food” nearly a century ago. You’ll visit nightclubs, hamburger joints, and a bathhouse that feeds customers on holidays. Stepping back, you’ll read about AIDS activism at gay-friendly establishments, and mostly gay neighborhood watering holes. Go underground at a basement bar; keep tripping and meet proprietors, managers, customers and performers. Then take a peek into the future, as Piepenburg sees it.

The locales profiled in “Dining Out” may surprise you because of where they can be found; some of the hot-spots practically beg for a road trip.

After reading this book, you’ll feel welcome at any of them.

If these books don’t shed enough light on queer food, then head to your favorite bookstore or library and ask for help finding more. The booksellers and librarians there will put cookbooks and history books directly in your hands, and they’ll help you find more on the history and culture of the food you eat. Grab them and you’ll agree, they’re pretty tasty reads.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

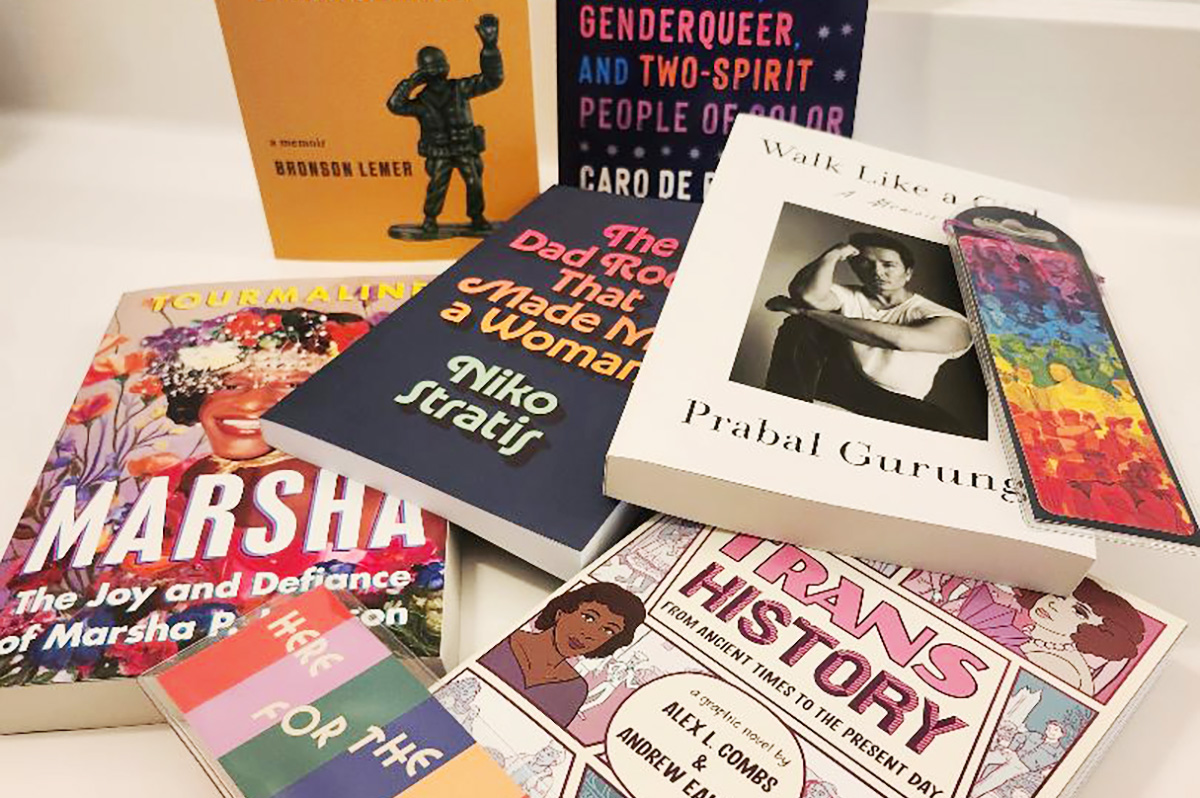

You’re going to be on your feet a lot this month.

Marching in parades, dancing in the streets, standing up for people in your community. But you’re also likely to have some time to rest and reflect – and with these great new books, to read.

First, dip into a biography with “Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson” by Tourmaline (Tiny Rep Books, $30), a nice look at an icon who, rumor has it, threw the brick that started a revolution. It’s a lively tale about Marsha P. Johnson, her life, her activism before Stonewall and afterward. Reading this interesting and highly researched history is a great way to spend some time during Pride month.

For the reader who can’t live without music, try “The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman” by Niko Stratis (University of Texas Press, $27.95), the story of being trans, searching for your place in the world, and finding it in a certain comfortable genre of music. Also look for “The Lonely Veteran’s Guide to Companionship” by Bronson Lemer (University of Wisconsin Press, $19.95), a collection of essays that make up a memoir of this and that, of being queer, basic training, teaching overseas, influential books, and life.

If you still have room for one more memoir, try “Walk Like a Girl” by Prabal Gurung (Viking, $32.00). It’s the story of one queer boy’s childhood in India and Nepal, and the intolerance he experienced as a child, which caused him to dream of New York and the life he imagined there. As you can imagine, dreams and reality collided but nonetheless, Gurung stayed, persevered, and eventually became an award-winning fashion designer, highly sought by fashion icons and lovers of haute couture. This is an inspiring tale that you shouldn’t miss.

No Pride celebration is complete without a history book or two.

In “Trans History: From Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Alex L. Combs & Andrew Eakett ($24.99, Candlewick Press), you’ll see that being trans is something that’s as old as humanity. One nice part about this book: it’s in graphic novel form, so it’s lighter to read but still informative. Lastly, try “So Many Stars: An Oral History of Trans, Nonbinary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit People of Color” by Caro De Robertis (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $32.00) a collection of thoughts, observations, and truths from over a dozen people who share their stories. As an “oral history,” you’ll be glad to know that each page is full of mini-segments you can dip into anywhere, read from cover to cover, double-back and read again. It’s that kind of book.

And if these six books aren’t enough, if they don’t quite fit what you crave now, be sure to ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for help. There are literally tens of thousands of books that are perfect for Pride month and beyond. They’ll be able to determine what you’re looking for, and they’ll put it directly in your hands. So stand up. March. And then sit and read.

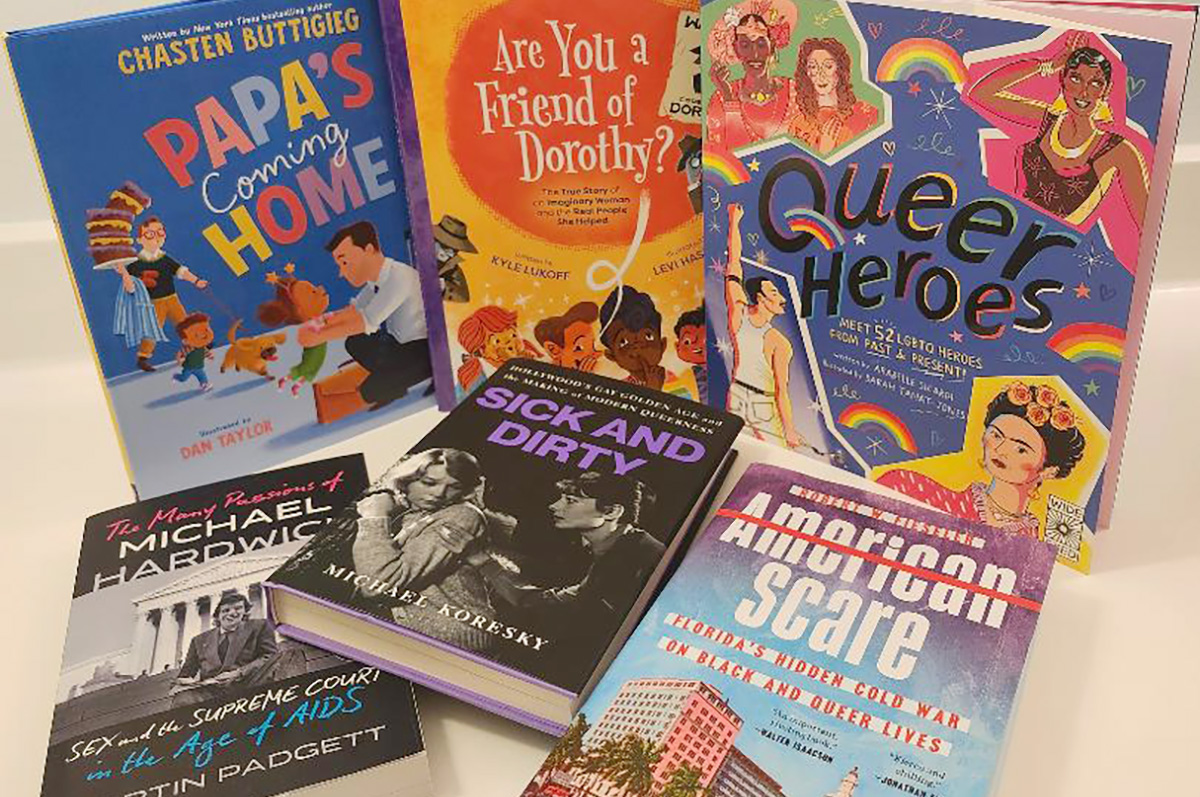

You’ve done your share of marching.

You’re determined to wring every rainbow-hued thing out of this month. The last of the parties hasn’t arrived yet, neither have the biggest celebrations and you’re primed but – OK, you need a minute. So pull up a chair, take a deep breath, and read these great books on gay history, movies, and more.

You probably don’t need to be told that harassment and discrimination was a daily occurrence for gay people in the past (as now!), but “American Scare: Florida’s Hidden Cold War on Black and Queer Lives” by Robert W. Fieseler (Dutton, $34) tells a story that runs deeper than you may know. Here, you’ll read a historical expose with documented, newly released evidence of a systemic effort to ruin the lives of two groups of people that were perceived as a threat to a legislature full of white men.

Prepared to be shocked, that’s all you need to know.

You’ll also want to read the story inside “The Many Passions of Michael Hardwick: Sex and the Supreme Court in the Age of AIDS” by Martin Padgett (W.W. Norton & Company, $31.99), which sounds like a novel, but it’s not. It’s the story of one man’s fight for a basic right as the AIDS crisis swirls in and out of American gay life and law. Hint: this book isn’t just old history, and it’s not just for gay men.

Maybe you’re ready for some fun and who doesn’t like a movie? You know you do, so you’ll want “Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness” by Michael Koresky (Bloomsbury, $29.99). It’s a great look at the Hays Code and what it allowed audiences to see, but it’s also about the classics that sneaked beneath the code. There are actors, of course, in here, but also directors, writers, and other Hollywood characters you may recognize. Grab the popcorn and settle in.

If you have kids in your life, they’ll want to know more about Pride and you’ll want to look for “Pride: Celebrations & Festivals” by Eric Huang, illustrated by Amy Phelps (Quarto, $14.99), a story of inclusion that ends in a nice fat section of history and explanation, great for kids ages seven-to-fourteen. Also find “Are You a Friend of Dorothy? The True Story of an Imaginary Woman and the Real People She Helped Shape” by Kyle Lukoff, illustrated by Levi Hastings (Simon & Schuster, $19.99), a lively book about a not-often-told secret for kids ages six-to-ten; and “Papa’s Coming Home” by Chasten Buttigieg, illustrated by Dan Taylor (Philomel, $19.99), a sweet family tale for kids ages three-to-five.

Finally, here’s a tween book that you can enjoy, too: “Queer Heroes” by Arabelle Sicardi, illustrated by Sarah Tanat-Jones (Wide Eyed, $14.99), a series of quick-to-read biographies of people you should know about.

Want more Pride books? Then ask your favorite bookseller or librarian for more, because there are so many more things to read. Really, the possibilities are almost endless, so march on in.

Books

A boy-meets-boy, family-mess story with heat

New book offers a stunning, satisfying love story

‘When the Harvest Comes’

By Denne Michele Norris

c.2025, Random House

$28/304 pages

Happy is the bride the sun shines on.

Of all the clichés that exist about weddings, that’s the one that seems to make you smile the most. Just invoking good weather and bright sunshine feels like a cosmic blessing on the newlyweds and their future. It’s a happy omen for bride and groom or, as in the new book “When the Harvest Comes” by Denne Michele Norris, for groom and groom.

Davis Freeman never thought he could love or be loved like this.

He was wildly, wholeheartedly, mind-and-soul smitten with Everett Caldwell, and life was everything that Davis ever wanted. He was a successful symphony musician in New York. They had an apartment they enjoyed and friends they cherished. Now it was their wedding day, a day Davis had planned with the man he adored, the details almost down to the stitches in their attire. He’d even purchased a gorgeous wedding gown that he’d never risk wearing.

He knew that Everett’s family loved him a lot, but Davis didn’t dare tickle the fates with a white dress on their big day. Everett’s dad, just like Davis’s own father, had considerable reservations about his son marrying another man – although Everett’s father seemed to have come to terms with his son’s bisexuality. Davis’s father, whom Davis called the Reverend, never would. Years ago, father and son had a falling-out that destroyed any chance of peace between Davis and his dad; in fact, the door slammed shut to any reconciliation.

But Davis tried not to think about that. Not on his wedding day. Not, unbeknownst to him, as the Reverend was rushing toward the wedding venue, uninvited but not unrepentant. Not when there was an accident and the Reverend was killed, miles away and during the nuptials.

Davis didn’t know that, of course, as he was marrying the love of his life. Neither did Everett, who had familial problems of his own, including homophobic family members who tried (but failed) to pretend otherwise.

Happy is the groom the sun shines on. But when the storm comes, it can be impossible to remain sunny.

What can be said about “When the Harvest Comes?” It’s a romance with a bit of ghost-pepper-like heat that’s not there for the mere sake of titillation. It’s filled with drama, intrigue, hate, characters you want to just slap, and some in bad need of a hug.

In short, this book is quite stunning.

Author Denne Michele Norris offers a love story that’s everything you want in this genre, including partners you genuinely want to get to know, in situations that are real. This is done by putting readers inside the characters’ minds, letting Davis and Everett themselves explain why they acted as they did, mistakes and all. Don’t be surprised if you have to read the last few pages twice to best enjoy how things end. You won’t be sorry.

If you want a complicated, boy-meets-boy, family-mess kind of book with occasional heat, “When the Harvest Comes” is your book. Truly, this novel shines.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

Chronicling disastrous effects of ‘conversion therapy’

New book uncovers horror, unexpected humor of discredited practice

‘Shame-Sex Attraction: Survivors’ Stories of Conversion Therapy’

By Lucas F. W. Wilson

c.2025, Jessica Kingsley Publishers

$21.95/190 pages

You’re a few months in, and it hasn’t gotten any easier.

You made your New Year’s resolutions with forethought, purpose, and determination but after all this time, you still struggle, ugh. You’ve backslid. You’ve cheated because change is hard. It’s sometimes impossible. And in the new book, “Shame-Sex Attraction” by Lucas F. W. Wilson, it can be exceptionally traumatic.

Progress does not come without problems.

While it’s true that the LGBTQ community has been adversely affected by the current administration, there are still things to be happy about when it comes to civil rights and acceptance. Still, says Wilson, one “particularly slow-moving aspect… has been the fight against what is widely known as conversion therapy.”

Such practices, he says, “have numerous damaging, death-dealing, and no doubt disastrous consequences.” The stories he’s collected in this volume reflect that, but they also mirror confidence and strength in the face of detrimental treatment.

Writer Gregory Elsasser-Chavez was told to breathe in something repellent every time he thought about other men. He says, in the end, he decided not to “pray away the gay.” Instead, he quips, he’d “sniff it away.”

D. Apple became her “own conversation therapist” by exhausting herself with service to others as therapy. Peter Nunn’s father took him on a surprise trip, but the surprise was a conversion facility; Nunn’s father said if it didn’t work, he’d “get rid of” his 15-year-old son. Chaim Levin was forced to humiliate himself as part of his therapy.

Lexie Bean struggled to make a therapist understand that they didn’t want to be a man because they were “both.” Jordan Sullivan writes of the years it takes “to re-integrate and become whole” after conversion therapy. Chris Csabs writes that he “tried everything to find the root of my problem” but “nothing so far had worked.”

Says Syre Klenke of a group conversion session, “My heart shattered over and over as people tried to console and encourage each other…. I wonder if each of them is okay and still with us today.”

Here’s a bit of advice for reading “Shame-Sex Attraction”: dip into the first chapter, maybe the second, then go back and read the foreword and introduction, and resume.

The reason: author Lucas F. W. Wilson’s intro is deep and steep, full of footnotes and statistics, and if you’re not prepared or you didn’t come for the education, it might scare you away. No, the subtitle of this book is likely why you’d pick the book up so because that’s what you really wanted, indulge before backtracking.

You won’t be sorry; the first stories are bracing and they’ll steel you for the rest, for the emotion and the tears, the horror and the unexpected humor.

Be aware that there are triggers all over this book, especially if you’ve been subjected to anything like conversion therapy yourself. Remember, though, that the survivors are just that: survivors, and their strength is what makes this book worthwhile. Even so, though “Shame-Sex Attraction” is an essential read, that doesn’t make it any easier.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

‘Pronoun Trouble’ reminds us that punctuation matters

‘They’ has been a shape-shifter for more than 700 years

‘Pronoun Trouble’

By John McWhorter

c.2025, Avery

$28/240 pages

Punctuation matters.

It’s tempting to skip a period at the end of a sentence Tempting to overuse exclamation points!!! very tempting to MeSs with capital letters. Dont use apostrophes. Ask a question and ignore the proper punctuation commas or question marks because seriously who cares. So guess what? Someone does, punctuation really matters, and as you’ll see in “Pronoun Trouble” by John McWhorter, so do other parts of our language.

Conversation is an odd thing. It’s spontaneous, it ebbs and flows, and it’s often inferred. Take, for instance, if you talk about him. Chances are, everyone in the conversation knows who him is. Or he. That guy there.

That’s the handy part about pronouns. Says McWhorter, pronouns “function as shorthand” for whomever we’re discussing or referring to. They’re “part of our hardwiring,” they’re found in all languages, and they’ve been around for centuries.

And, yes, pronouns are fluid.

For example, there’s the first-person pronoun, I as in me and there we go again. The singular I solely affects what comes afterward. You say “he-she IS,” and “they-you ARE” but I am. From “Black English,” I has also morphed into the perfectly acceptable Ima, shorthand for “I am going to.” Mind blown.

If you love Shakespeare, you may’ve noticed that he uses both thou and you in his plays. The former was once left to commoners and lower classes, while the latter was for people of high status or less formal situations. From you, we get y’all, yeet, ya, you-uns, and yinz. We also get “you guys,” which may have nothing to do with guys.

We and us are warmer in tone because of the inclusion implied. She is often casually used to imply cars, boats, and – warmly or not – gay men, in certain settings. It “lacks personhood,” and to use it in reference to a human is “barbarity.”

And yes, though it can sometimes be confusing to modern speakers, the singular word “they” has been a “shape-shifter” for more than 700 years.

Your high school English teacher would be proud of you, if you pick up “Pronoun Trouble.” Sadly, though, you might need her again to make sense of big parts of this book: What you’ll find here is a delightful romp through language, but it’s also very erudite.

Author John McWhorter invites readers along to conjugate verbs, and doing so will take you back to ancient literature, on a fascinating journey that’s perfect for word nerds and anyone who loves language. You’ll likely find a bit of controversy here or there on various entries, but you’ll also find humor and pop culture, an explanation for why zie never took off, and assurance that the whole flap over strictly-gendered pronouns is nothing but overblown protestation. Readers who have opinions will like that.

Still, if you just want the pronoun you want, a little between-the-lines looking is necessary here, so beware. “Pronoun Trouble” is perfect for linguists, writers, and those who love to play with words but for most readers, it’s a different kind of book, period.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

New book helps vulnerable people to stay safe

‘The Cost of Fear’

By Meg Stone

c.2025, Beacon Press

$26.95/232 pages

The footsteps fell behind you, keeping pace.

They were loud as an airplane, a few decibels below the beat of your heart. Yes, someone was following you, and you shouldn’t have let it happen. You’re no dummy. You’re no wimp. Read the new book, “The Cost of Fear” by Meg Stone, and you’re no statistic. Ask around.

Query young women, older women, grandmothers, and teenagers. Ask gay men, lesbians, and trans individuals, and chances are that every one of them has a story of being scared of another person in a public place. Scared – or worse.

Says author Meg Stone, nearly half of the women in a recent survey reported having “experienced… unwanted sexual contact” of some sort. Almost a quarter of the men surveyed said the same. Nearly 30 percent of men in another survey admitted to having “perpetrated some form of sexual assault.”

We focus on these statistics, says Stone, but we advise ineffectual safety measures.

“Victim blame is rampant,” she says, and women and LGBTQ individuals are taught avoidance methods that may not work. If someone’s in the “early stages of their careers,” perpetrators may still hold all the cards through threats and career blackmail. Stone cites cases in which someone who was assaulted reported the crime, but police dropped the ball. Old tropes still exist and repeating or relying on them may be downright dangerous.

As a result of such ineffectiveness, fear keeps frightened individuals from normal activities, leaving the house, shopping, going out with friends for an evening.

So how can you stay safe?

Says Stone, learn how to fight back by using your whole body, not just your hands. Be willing to record what’s happening. Don’t abandon your activism, she says; in fact, join a group that helps give people tools to protect themselves. Learn the right way to stand up for someone who’s uncomfortable or endangered. Remember that you can’t be blamed for another person’s bad behavior, and it shouldn’t mean you can’t react.

If you pick up “The Cost of Fear,” hoping to learn ways to protect yourself, there are two things to keep in mind.

First, though most of this book is written for women, it doesn’t take much of a leap to see how its advice could translate to any other world. Author Stone, in fact, includes people of all ages, genders, and all races in her case studies and lessons, and she clearly explains a bit of what she teaches in her classes. That width is helpful, and welcome.

Secondly, she asks readers to do something potentially controversial: she requests changes in sentencing laws for certain former and rehabilitated abusers, particularly for offenders who were teens when sentenced. Stone lays out her reasoning and begs for understanding; still, some readers may be resistant and some may be triggered.

Keep that in mind, and “The Cost of Fear” is a great book for a young adult or anyone who needs to increase alertness, adopt careful practices, and stay safe. Take steps to have it soon.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

A taste for the macabre with a side order of sympathy

New book ‘The Lamb’ is for fans of horror stories

‘The Lamb: A Novel’

By Lucy Rose

c.2025, Harper

$27.99/329 pages

What’s for lunch?

You probably know at breakfast what you’re having a few hours later. Maybe breast of chicken in tomato sauce. Barbecued ribs, perhaps? Leg of lamb, beef tongue, pickled pigs’ feet, liver and onions, the possibilities are just menus away. Or maybe, as in the new book, “The Lamb” by Lucy Rose, you’ll settle for a rump roast and a few lady fingers.

Margot was just four years old when she noticed the mold on the shower walls, and wondered what it might taste like. She also found fingers in the shower drain from the last “stray,” the nails painted purple, and she wondered why they hadn’t been nibbled, too.

Cooked right, fingers and rumps were the best parts.

Later, once Margot started school, Mama depended on her to bring strays from the woods to their cottage, and Mama would give them wine and warm them up. She didn’t often leave the house unless it was to bury clothing and bones, but she sometimes welcomed a gardener who was allowed to leave. There was a difference, you see, between strays and others.

But Eden? Margot couldn’t quite figure her out.

She actually liked Eden, who seemed like a stray but obviously wasn’t. Eden was pretty; she never yelled at Margot, although she did take Margot’s sleeping spot near Mama. Eden made Mama happy; Margot could hear them in the bedroom sometimes, making noises like Mama did when the gardener visited. Eden was a very good cook. She made Mama softer, and she made promises for better times.

And yet, things never got better. Margot was not supposed to call attention to herself, but she wanted friends and a real life. If she was honest, she didn’t want to eat strays anymore, either, she was tired of the pressure to bring home dinner, and things began to unravel. Maybe Mama didn’t love Margot anymore. Maybe she loved Eden better or maybe Mama just ached from hunger.

Because you know what they say: two’s company, three’s a meal.

Not a book to read at lunch? No, probably not – although once you become immersed in “The Lamb,” it’ll be easy to swallow and hard to put down.

For sure, author Lucy Rose presents a somewhat coming-of-age chiller with a gender-twisty plot line here, and while it’s occasionally a bit slow and definitely cringey, it’s also really quite compelling. Rose actually makes readers feel good about a character who indulges in something so entirely, repulsively taboo, which is a very surprising – but oddly satisfying – aspect of this unique tale. Readers, in fact, will be drawn to the character Margo’s innocence-turned-eyes-wide-open and it could make you grow a little protective of her as she matures over the pages. That feeling plays well inside the story and it makes the will-they-won’t-they ending positively shivery.

Bottom line, if you have a taste for the macabre with a side order of sympathy, then “The Lamb” is your book and don’t miss it. Fans of horror stories, this is a novel you’ll eat right up.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

‘Cleavage’ explores late-in-life transition

An enjoyable collection of work from a born storyteller

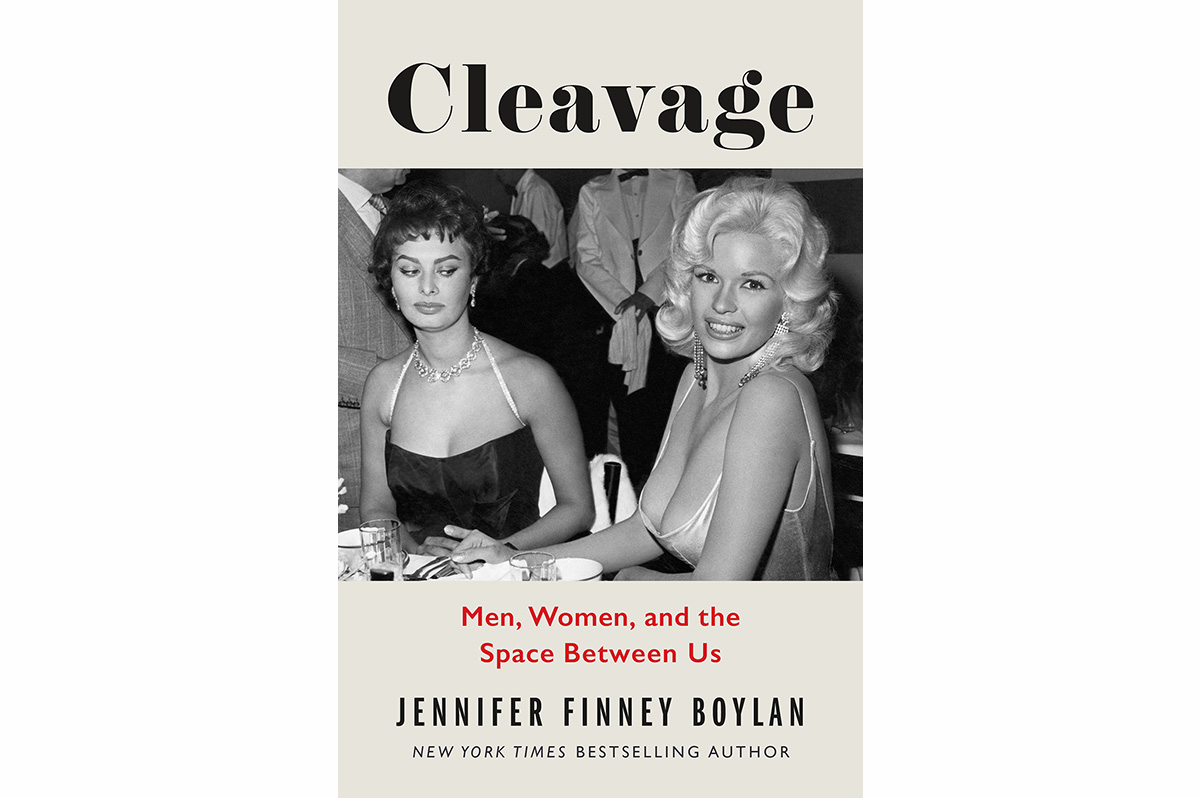

‘Cleavage: Men, Women, and the Space Between Us’

By Jennifer Finney Boylan

c.2025, Celadon Books

$29/256 pages

When it came to friends and family, your cup used to runneth over.

You had plenty of both and then, well, life and politics wedged an ocean-sized chasm between you and it makes you sad. And yet – are you really all that far apart? As in the new memoir, “Cleavage” by Jennifer Finney Boylan, maybe you’re still two peas in a pod.

Once upon a time not so long ago, Jennifer Finney Boylan was one of “a group of twelve-year-old Visigoths” intent on mischief. They hung around, did normal boy stuff, setting off rockets, roughhousing, roaming, rambling, and bike-riding. The difference between Boylan and the other boys in her group was that Jim Boylan knew she was really a girl.

Then, she vowed that it was a “secret no soul would ever know,” and James went to college, enjoyed a higher metabolism, dated, fell in love too easily, then married a woman and fathered two boys but there was still that tug. Boylan carried the child she once was in her heart – “How I loved the boy I’d been!” – but she was a woman “on the inside” and saying it aloud eventually became critical.

Boylan had a hard talk with her wife, Deedie, knowing that it could be the end of their marriage. She’s eternally grateful now that it wasn’t.

She’s also grateful that she became a woman when she did, when politics had little to do with that personal decision. She worries about her children, one who is trans, both of whom are good, successful people who make Boylan proud. She tries to help other trans women. And she thinks about the words her mother often said: “Love will prevail.”

“Our lives are not a thing to be ashamed of,” Boylan says, “or apologized for, or explained. Our lives are a thing of wildness, and tenderness, and joy.”

Judge “Cleavage” by its cover, and you might think you’ll get a primer on anatomy. Nope, author Jennifer Finney Boylan only has one chapter on the subject, among many. Instead, she leans heavily on her childhood and her transition rather late in life, her family, and her friends to continue where her other books left off, to update, correct, and to share her thoughts on that invisible division. In sum, she guesses that “a huge chunk of the population… still doesn’t understand this trans business at all.”

Let that gentle playfulness be a harbinger of what you’ll read: some humor about her journey, and many things that might make your heart hurt; self-inspection that seems confidential and a few oh-so-deliciously well-placed snarks; and memories that, well told and satisfying, are both nostalgic and personal from “both the Before and the After.”

This book has the feel of having a cold one with a friend and Boylan fans will devour it. It’s also great for anyone who is trans-curious or just wants to read an enjoyable collection of work from a born storyteller. No matter what you want from it, what you’ll find in “Cleavage” is a treasure chest.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoWest Hollywood to advance protections for diverse and non-nuclear families

-

Commentary4 days ago

Commentary4 days agoThe Supreme Court’s ‘Don’t Read Gay’ ruling

-

Arts & Entertainment3 days ago

Arts & Entertainment3 days ago2025 Emmy nominations: ‘Hacks’ and ‘The Last of Us’ bring queer excellence to the table

-

a&e features4 days ago

a&e features4 days agoThe art of controlled chaos: Patrick Bristow brings the Puppets to life

-

Movies3 days ago

Movies3 days ago‘Superman’ is here to to save us, despite MAGA backlash

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoHololive and Dodgers create a home for queer fandom

-

Events2 days ago

Events2 days agoLos Angeles Blade to take special part in NLGJA Los Angeles inaugural journalism awards

-

Features7 hours ago

Features7 hours agoTS Madison Starter House offers a blueprint for Black, trans liberation