Features

Out West Hollywood Mayor Sepi Shyne will run to replace Schiff

“I realized my purpose is to illuminate- I did with my family & my advocacy work. I’ve done the same to illuminate & elevate people”

WEST HOLLYWOOD – West Hollywood Mayor Sepi Shyne announced at noon Tuesday her plans to run for the congressional seat currently held by Rep. Adam Schiff, who is running to replace California’s senior U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein who is retiring in 2024.

Shyne, the first Iranian queer female Mayor, took time out of her schedule to speak to the Blade about a lifetime of combatting prejudice, hate, and violence.

Campaign advert announcing Shyne’s candidacy:

POLITICS

“I realized my purpose is to illuminate. This is what I did with my family and in my advocacy work. I’ve done the same to illuminate and elevate the people.”

Mayor Shyne received her Bachelor of Science from San Jose State University with a double concentration in Accounting and Management Information Systems and a Minor in Drama with an emphasis in Directing. She received her Juris Doctorate with a specialization certificate in litigation from Golden Gate University School of Law in San Francisco.

She then served on the City of West Hollywood’s Lesbian and Gay Advisory Board (now LGBTQ+ Advisory Board), on the City of West Hollywood’s Business License Commission, and on the Los Angeles County Assessor’s Advisory Council on which she continues to serve.

Additionally, she has led many boards and organizations, including the LGBT Bar Association of Los Angeles and as a Board of Governor and Steering Committee leader with the Human Rights Campaign Los Angeles.

Shyne is a Co-Organizer of WeHo Neighbors Helping Neighbors, a community group created during the pandemic to help get resources to seniors, people with disabilities, and people in immunosuppressed households via social media and volunteer check-in calls. In every board and organization she has led, she has recruited and elevated women and people of color to leadership positions to create more diversity, inclusion, and equity.

“In the LBGT organizations and human rights campaigns, I was always fighting for equality,” said Shyne. “I made sure I brought in women and women of color into leadership positions because that was greatly lacking.”

Shyne was encouraged by her peers to run for office.

“I started learning more about the city, and I didn’t know that West Hollywood only had one queer woman in office in its entire, at that time, thirty-six years. That’s it. And no women of color ever in elected office.”

“I lived in the city for ten years. I really wanted the city to get back to its progressive ways. I felt it had really lost its purpose.”

“I felt that West Hollywood had lost its way. There were so many LGBTQ folks under our umbrella who didn’t feel included in our community. I knew having representation in office would inspire others as it did for me.”

“We have done so much in changing our ordinances so that our trans siblings feel more welcome, and there is still more work to do. The bisexual community that is still so often ostracized gets discrimination from straight folks and lesbians and gays.”

“My wife and I separated in June. She was bisexual. When I was on the advisory board, we had the first bisexual pride celebration, and I was so glad that we did that. Since then, we have dedicated funds to Bi Pride week in West Hollywood.”

“I didn’t realize all this until after I had a deep spiritual awakening. I am a lawyer, but I am also an energy healer. My company is called Soulillume.”

“I realized my purpose is to illuminate. This is what I did with my family and in my advocacy work. I’ve done the same to illuminate and elevate the people.”

FLEEING IRAN

Born in Iran, Shyne was two years old when the revolution happened in her hometown in Tehran, Iran’s capital. The Iranian Revolution, also known as the Islamic revolution, was a period of violent takeover by the Islamic regime that ultimately ended the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979 and resulted in the Imperial State of Iran being replaced by the Islamic State of Iran.

“As a little girl, my whole life turned upside down,” Shyne told The Blade.

“It was very traumatic to experience the chaos around me, the chaos that my family was experiencing, and all the women when the revolutionary guard and Islamic regime came in. For a little kid, it felt like it happened overnight. They implemented so many rules. There were no more clubs. Women could not wear makeup. No drinking. Women couldn’t be in the streets with men anymore, and they had to wear the hijab.”

“And it was violent.”

“They would whip people in the streets. They would torture people. Free speech was being taken away.”

As it is for so many children of the time, the brutality of the Islamic takeover took a deep toll on Shyne’s childhood.

“Everyone was in shock. Everyone was going through trauma. There wasn’t time for my parents to take care of me. I learned that I needed to take care of myself because the adults could barely take care of themselves.”

Following the end of the revolution in 1979, the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) continued to ravage the lives of Iranians, creating even more tragedy and chaos.

“It was very traumatic when the war started,” said Shyne. “When they were getting closer to Tehran, we would hear the sirens and the jets, and we would run down to the basement because of the fear of being bombed.”

Shyne told the Blade that her constant fear for her safety was further exacerbated by her gender: “I was so scared to be a girl because being a girl meant violence.”

In Tehran, Shyne lived on the top floor of a triplex and would often play soccer with her downstairs neighbors. Because she was fearful of what might happen to her as a young girl playing in the streets, Shyne created a male alias to make her feel safer.

“My hair was short,” said Shyne. “I made up a boy name, Parviz, and told the neighborhood boys I was Parviz.”

Sadly, as Shyne stated, times were terrifying for both men and women.

“They put my dad in prison for speaking against the regime. Then he started planning our escape from Iran.”

Shyne’s father made visa arrangements for their family but was unable to secure a visa for Shyne’s fifteen-year-old brother, who was of drafting age for the war.

“Those boys were all dying on the front lines,” Shyne told The Blade. “So they smuggled him out of the country. They sent him off with some stranger.”

Shyne, age five at the time, was concerned for her brother, whom she described as her “protector.” The family made their way to Italy, where they remained for a while before finally arriving in America. Her brother arrived safely as well.

The move to America in September of 1982 saved Shyne’s life in more ways than one. “My mom had no idea my dad planned to stay here permanently. But he had made a plan with my eldest brother that that was the right thing to do. That may not have been the best thing to do in a marriage, but as a little girl who was a lesbian, I don’t think I would have survived if he had not done that.”

While America proved to be safer for Shyne’s family than Tehran, times were anything but easy,

“It was a very difficult time for Iranians here with xenophobia and Islamophobia. People would see these Islamic extremists saying death to America and associate them with us, so we started calling ourselves Persian. All the while, we didn’t know if our families were going to be killed.”

Shyne’s family moved to her sister’s home in Cupertino, CA, where Shyne attended school.

“I was undocumented until I was 16. But I was able to go to school. I was supposed to have started school in Iran. There, you learn English, Arabic, and Farsi. But my dad hadn’t wanted me to start because he didn’t like that we also had to learn Islam, which they were forcing on the kids.”

Because Shyne had not started learning English in Tehran, she struggled in her first years of schooling in Cupertino.

“I didn’t speak very much English. Some girls started bullying me. They started throwing wood chips at me, calling me ‘camel head’ and ‘terrorist’ because they knew I was Iranian. I ran over to one of the school’s adult volunteers on yard duty. Because I didn’t know how to speak English, I couldn’t explain that I was being bullied. I was the one who ended up getting detention.”

“That day was one of my first lessons about the importance of knowledge. I told myself, ‘You need to learn English as soon as possible to speak up for yourself.’ My mom told me I used to have nightmares and that my first words in English were, ‘Leave me alone.'”

COMING OUT

Shyne, who, like many immigrant children, felt that she was living two lives, one at home and one in school, feels that learning to stand up for herself was a pivotal moment in her life. The next pivotal moment was coming out.

While she may not have had the support or language to express it at the time, Shyne knew she was queer from a very young age.

“I remember being in Iran at age 4 or 5 and having a crush on my neighbor. I remember sitting on the entry steps to the building and holding her hand, and kissing her cheek. It just felt naturally right to me. Then around eight years old, I had a lot of cousins who ended up emigrating here, and they were talking about boys, boys, boys. I thought, ‘Wait. I’m a girl. They are girls. But they keep talking about boys. But I’m attracted to girls.'”

While Shyne knew she was attracted to girls, actually defining herself as a lesbian took some time.

“When I hit puberty, I thought maybe I was bisexual. I kissed so many boys in high school, and I just didn’t feel anything. But I would say to my close friends that I’m bisexual because I knew deep down that I was into girls. When I was fifteen, I fell in love with my best friend. It was completely emotional because we were young, and she was Mormon. She was definitely one of my soulmates.”

However, Shyne’s love for her first soulmate was put to an end.

“She had such a difficult life,” explained Shyne. “She was getting a lot of pressure from her Mormon family over me. They told her, ‘Sepi is taking you down the wrong path.’ But we were actually the best kids. We would just drive around and play music and dance around my car. I love to dance. But there was so much homophobia at the time. So much. She actually freaked out at some point and stopped talking to me for a few years.”

Around the same time, when Shyne was seventeen, she connected with her first-ever girlfriend.

“There was one girl who came up to me and said, ‘Hey, Sepi, I have some playboy magazines at home. I would love for you to come over and look at them with me.’ She was very attractive. I went over to her house. That was the first time I kissed a girl. It was fireworks. It was like how it was on TV when boys and girls would kiss. She was my first girlfriend.”

I called my best friend, and I said, ‘Oh my gosh. This is what happened. Maryanne and I made out. I’m totally not bisexual. I need to figure out how to come out to my family.'”

“So I came out to the younger family members first. Then I came out to my mom when I was nineteen. She realized I had stopped dating boys, and my parents were constantly trying to set me up, which is very prevalent in the Iranian community. I was so uncomfortable it was awful.”

Shyne’s queerness was difficult for her traditionalist mother to process, so Shyne, always the educator, gave her mother some recommended reading, including Betty DeGeneris’ book about her daughter, Ellen DeGeneres coming out, and another book called Prayers for Bobby by Leroy Aarons.

“My mom said, ‘don’t tell your dad.’ My dad was vocally homophobic. She also said, ‘Don’t get into a relationship too soon. Go experience as much as you want.’ She thought it was a phase.”

“Then she grieved as many parents do. She was in denial, then she was angry, and she said, ‘I hate you. You’re not my daughter.’ Instead of internalizing it, I said, ‘Okay. I need to educate my family because they don’t know better.'”

Shyne’s involvement in politics stemmed from a deeply personal place. In addition to her lifelong journey with her queerness, The Mayor recalled one hate incident that fueled her need to make a difference.

“I ended up getting together with my best friend,” said Shyne. “When we were in college, we were still trying to plan out what we wanted for the rest of our lives. We were at a gay-friendly coffee bar, talking about what grad schools we wanted to go to. We didn’t know the management had changed. We were just holding hands. The next thing I knew, the manager and a police officer showed up and said, ‘You need to leave. The establishment doesn’t want your kind here.’ Then he blew a kiss and winked at me.

“We couldn’t call our families. They were already worried about us as it was. We were driving around town crying. We felt demoralized. We felt powerless.”

“Finally, I pulled over and said to her, ‘I’m tired of feeling powerless. We need to go to law school and learn the law and stop this.’ So that was what we did.”

HATE SPEECH

Shyne’s method of educating others has continued to serve her in her professional life.

“When people have hate speech about a group, I utilize the way I educated my family. We saw this with marriage equality as well. People did not understand why it was important until we shared our side from a vulnerable place.”

As a political figure, Shyne has received a tremendous amount of hate speech and personal threats for being a queer Iranian, woman. Amid the plethora of ignorance, one person commented on one of Shyne’s videos, “We don’t want a Muslim terrorist running city hall, if you come to my door, I’m going to mace you.”

After some misinformation was printed about one of Shyne’s policies, she received the following message from an Outlook account: “You piece of shit queer bitch. I hope you get robbed or raped or both.” The Mayor filed an official police report following the incident.

“When I’m getting personal attacks,” said Shyne, “if it’s a person that should know better, then it’s actually not my job if they are being abusive and engaging in toxic behavior to teach them that this is okay by allowing that. It is my job to stand up for myself and let them know that is not what I am willing to entertain by setting boundaries. There has been a lot of hate since I was elected office, from strangers to people in the community to local blogs printing so much misinformation.”

Shyne also blames the platforms themselves for allowing this type of hate speech and misinformation to spread, unregulated, through their comment sections.

“These platforms are aware of it, and they allow a comment section to exist with racist posts. They allow misogyny. They allow transphobia. This is a choice. These are values they put out in the community. They are choosing to do this even though they are a part of the community and have likely experienced discrimination themselves. So this is very sad.”

When asked what she believed should be done to end hate speech online, Shyne said she believed more regulation and transparency should be enforced.

“I think these platforms need to come out very strongly against hate speech. It is very simple. Just take a stand for people. If their lawyers are saying this is protected speech, then as a corporation, they can take a stance. They can use their algorithms and all their technology and institute their community standards.”

“They need to apply the standards that they have equally,” continued Shyne. “They should be able to monitor and speak up against hate speech. It is easy to tell what’s right and what’s not right. Sadly, since 2016 there has been so much lack of civility. Everybody is just pointing fingers at each other. This is happening within each party too. The republicans are fighting. The democrats are fighting. Everyone is focused on making each other wrong instead of sitting down and just listening.”

“When social media started, I think they didn’t anticipate the state of our world becoming so divisive as we saw with Nancy Pelosi’s husband. This hate speech absolutely does turn to violence.”

In September 2022, Governor Gavin Newsom announced that he signed a social media transparency bill (AB 578) by Assembly Member Jesse Gabriel, which will require social media companies to publicly post their policies regarding hate speech, disinformation, harassment, and extremism on their platforms, and report data on their enforcement of the policies.

Shyne feels that revising social media platform practices is vital as the laws that deal with inciting violence are now outdated in the face of this new technology.

“We also have to reconsider our laws about what is considered inciting violence because those laws didn’t consider social media at the time. When those laws were created, they were about people saying things in person and then asking whether or not it is probable that violence will ensue from that interaction. But now we have people on social media saying horrible things that do lead to violence.”

Shyne also sees an imbalance between protection for federal and local officials that needs to be corrected. Local officials need the same level of protection that federal officials have. She also stated that there is an imbalance of women, particularly women of color like The Mayor, getting a disproportionately large share of online hate speech.

A FINAL MESSAGE

Shyne shared a final message of hope with The Blade for the young leaders of the future.

“Always, no matter what your circumstance in life has been, if your life was difficult or traumatic, whatever anyone has said to you, whether strangers or close to you, if it is negative, don’t believe it. Just don’t believe it. Go within yourself and give yourself the healing you need to know that you are absolutely perfect as you are. You were born exactly as you were meant to be. You were meant to live a free, incredible, magical life. All the young people that are being born are so special. They are literally meant to shift this world into a much better place. No matter what, don’t ever give up. Step into your power and reach out to people like me and other leaders and ask for mentorship. Know that you can overcome any adversity. If you just set your mind to it, anything is possible.”

Features

What’s next for “local hero” and longtime queer ally Genevieve Morrill

Morrill served 15 defining years on WeHo’s Chamber of Commerce. We discuss her future and how queer advocacy can’t be ignored in her legacy.

It’s Feb. 4 when I sit down to call Genevieve Morrill, only a week after she officially stepped away from her longtime role as president and CEO of West Hollywood’s Chamber of Commerce. For 15 years, she paved the way for the City’s business ecosystem: creating robust opportunities for business owners and championing their rights.

Her leadership style has always been defined by forward-thinking, ambitious, and collectively-driven change. “I’m not here to tell you how to lead,” Morrill told the Blade. “I’m here to lead with you.” This focus on inclusivity and community empowerment stretched into advocacy for marginalized community members. From early on, Morrill has been a strong ally for BIPOC and LGBTQ+ people, creating pathways for diverse leaders and business owners.

Today, we dive into Morrill’s legacy of queer advocacy: one that has earned her this year’s “Local Hero” award at the upcoming Los Angeles Blade’s Best of LA Awards on Mar. 26.

Uplifting queer and trans people in the business sector

In West Hollywood, and Los Angeles more broadly, Morrill is known for her dedication to shaping and revitalizing dormant spaces. The Chamber was “in trouble” when the board asked her to take over leadership in 2010. They were struggling under the pressure of the recession, and the next steps looked risky and obfuscated. Morrill readily accepted the challenge, her internal armor strengthened by a childhood that was always on the move.

Morrill’s father was a Methodist minister and would often move the family around to take part in “community development work” across the globe. She felt propelled by a sense of duty and mission from a young age. “It’s kind of in my DNA… [I grew up] in an organization that was focused on caring for the world,” Morrill said, who also attributed her strong sense of justice and community-oriented service to her parents’ involvement in civil rights and the women’s movement.

Her responsibility to the people led to major reforms at the Chamber of Commerce: the board tripled its budget, increased membership by 20%, and created widespread visibility for small businesses across West Hollywood. Under her guidance, the Chamber also established a small business task force as well as its philanthropic Small Business Foundation: an organization dedicated to expanding opportunities and providing training for queer and BIPOC business owners, as well as other minority community members.

This all sprouted from Morrill’s keen eye: while immersing herself deeply in the beast of WeHo’s business ecosystem, she observed the lack of initiative employers would take when it came to hiring and empowering trans and queer workers. She began collaborating with Drian Juarez, then the vice president of programming at Trans Can Work: a local workforce development organization that supports transgender and gender nonconforming people.

In the early 2010s, Morrill and Juarez hosted their first seminar together, where fewer than 10 people attended. “It was a real challenge to get people there,” Morrill said, who explained to the Blade that, even a decade ago, business owners were hesitant to adapt queer inclusivity into their branding. Queer stigma continued to be rampant and widespread.

Morrill refused to accept this. For the next seminar focused on trans people in the workplace, she called various local businesses and pushed them to attend. “You need to get there,” she recounted, remembering that her tone was urgent and stern. Over 50 people attended this second seminar. She recalls this early foray into queer advocacy as one of her many “significant” achievements.

These workshops then formed into a steady program: WeLead Academy, a professional development opportunity that uplifts queer and BIPOC entrepreneurs. Over two months, participants learn about money management, leveraging technological advancement for business growth, collaborating within the community, navigating government systems, and other essential business skills. It is powered through the Chamber’s Small Business Foundation.

In her years of service to West Hollywood, Morrill set a precedent for this expansion of inclusivity: to ensure that the City’s wide, varied fabric of people felt represented and capable of unlocking success. Morrill also recognizes that the spaces around us are ever-changing, and rather than stay locked in old ways, she questions: how can we preserve the spirit and histories of our environment, while allowing for growth that takes us to a more equitable future?

She reflects on older conversations she had with the late LGBTQ+ rights activist Ivy Bottini, where they would often discuss the loss of lesbian and sapphic sanctuaries. Even within queer spaces, there is still a need to constantly recalibrate and think about who we’re leaving out of the conversation. But Morrill thinks about these dilemmas with hope and continues to stand in solidarity with the queer communities “being attacked and trying to be erased” right now.

What’s next for Morrill?

This new chapter ahead is marked by bittersweet excitement. On leaving the Chamber, Morrill explained that, as hard as it is to “break off” from these 15 memorable years and the space that defined her community work, it’s a necessary change.

This has been her whole life, up until now. “[When I] was asked if I was still going to leave at the end of 2025, my heart said no,” Morrill said. “But out of my mouth came: yes. I think my heart is still here in West Hollywood [and] with all the businesses…I know there’s still a need for somebody to defend and fight for them.” Morrill’s successor is Len Lanzi, whom Morrill trusts will lead the Chamber well in its next era.

A return to the arts?

When I ask Morrill what the future looks like ahead, she is unsure but excitedly brings up an old passion project: a nonprofit she started in 2007, called “Books with Feet.” The concept is rooted in her core love for theater, books, and the arts: classic short stories are performed so that every single word, even in narration, is performed with exciting and dynamic movement.

Here, Morrill directed stories on the stage: a place she found success in during her adolescence. She recounts performing in a hit show in Chicago and giving it her all during its 14-week run. She studied under acting legends in the 1980s, before beginning to coach students herself.

“I think what happened for me was I didn’t really have a desire to hit the pavement with my headshot,” Morrill said. “But I had a desire to continue to be immersed in the arts.” So she ran Books with Feet until 2011, when it became impossible to manage both this and her Chamber role. “So, I might get back to that. Who knows?” Morrill said.

As we talk more, her entrepreneurial, innovative spirit springs forward, ripe with possibility. She discusses the possibility of creating cultural hubs across the county, revamping “dumpy” abandoned theaters and transforming them into lively arts districts of their own. “I feel like the strings have been cut,” Morrill said, of this new liberating freedom she feels for her path ahead. “As that happens, more space will open up for me [and] that will help me understand what the universe is going to present to me.”

Celebrate Morrill with the Blade at our upcoming Best of LA Awards on Mar. 26, held at the Abbey in West Hollywood. More information can be found here.

Kristie Song is a California Local News Fellow placed with the Los Angeles Blade. The California Local News Fellowship is a state-funded initiative to support and strengthen local news reporting. Learn more about it at fellowships.journalism.berkeley.edu/cafellows.

Features

From the Desk of AJSOCAL: How the QTAPI community celebrates Lunar New Year

Our queer and trans Asian Pacific Islander siblings are celebrating the new year on Feb. 17, channeling chosen family, new traditions and the transformative power of the Fire Horse. Read how various local advocates are finding power and community in this time.

For many, the New Year starts on January 1st, but for some in the queer and trans Asian Pacific Islander (QTAPI) community, the new year begins in the middle of February. For many in the larger AAPI community, celebrations of the Lunar New Year mark the start of spring, bringing families together through reconnection, traditions, and shared meals.

Lunar New Year is a time when folks usually celebrate with family, but as LGBTQ+ folks, many of us have found a home or a safe space with our chosen families instead. As a result, we include traditions that are inherently “QTAPI,” blending our LGBTQ+ identities and our AAPI heritage. Today, we are highlighting a few diverse community leaders from our QTAPI community and how they are planning to celebrate the Year of the Fire Horse later this month.

For Chinese astrology enthusiasts, the last Year of the Fire Horse was observed in 1966, marking a generational return of passionate, expansive possibility and intense reconstruction and manifestation in 2026. If there’s a year to be brave and be intentional, the time is now – it’s not in the face of an oppressive government trying to deprive us of our futures.

Civil rights organization Asian Americans Advancing Justice Southern California (AJSOCAL) spoke with various QTAPI community leaders and allies about how they celebrate and renew the Lunar New Year through a queer and trans lens.

Viki Goto is the Board co-president of PFLAG San Gabriel Valley API Chapter, an organization that supports AAPI families with LGBTQ+ children.

Kay P. is a parent involved with PFLAG San Gabriel Valley API Chapter.

Maria Do is the Community Mobilization Manager for the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Kathy Khommarath is the Institutional Giving Manager at AJSOCAL.

Marshall Wong previously served as the principal author of Los Angeles County’s Human Relations Commission’s annual hate crime report, and spearheaded the queer and trans AAPI organization API Equality-LA, which was rebranded as Moonbow before its disbandment in 2025.

What does Lunar New Year mean to you?

Goto: Lunar New Year was always about eating good food for me. [But] once I learned more about the traditions and the history behind them, I realized that the Lunar New Year’s importance has expanded as a representation of Asian cultural heritage. As more communities across Southern California host festivals, parades, and educational events, a greater sense of belonging and appreciation for our unique stories is fostered among people with different cultural backgrounds. This is vital to creating an inclusive and affirming society where everyone is encouraged to be their authentic selves.P.: Growing up in a mostly white community in the Philadelphia suburbs, I didn’t know about Lunar New Year. It really wasn’t until I moved to California and saw that it was celebrated in my children’s schools that I felt that it was a real holiday, and it felt good to be represented. [It’s] a recognition of me and my Asian American community.

Do: Lunar New Year is traditionally a holiday spent with family. For me, this includes chosen family. While the turn of a new calendar year is often viewed as a time for personal reflection and goal setting, the Lunar New Year offers a chance to set those intentions with one’s community. It’s a celebration that is deeply hopeful, which is why I always look forward to it every year.

Khommarath: While I don’t personally celebrate Lunar New Year because I am Lao American, I deeply respect the holiday and the way many Asian communities mark it as a time of renewal and connection. In Lao culture, our major new year celebration is Pi Mai, or Lao New Year, which takes place in April. Even though the timing and customs differ, the spirit behind Lunar New Year feels intimately familiar. Both Lunar New Year and Lao New Year are centered on renewal, community, cleansing away the past year, and entering the new one with intention and joy.

Wong: The Lunar New Year is the most important celebration for two billion Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese people, and many other communities worldwide. It is a time for families and friends to come together to wish one another luck, prosperity, and progress in the coming year. Growing up, it was a time for beloved traditions, like parades, lion dances, firecrackers, special foods, and red envelopes containing lucky money for children. For many people, it involves rituals of ancestral worship, deep cleaning of homes to signify new beginnings, displaying decorations, and wearing special clothes.

How do you celebrate your QTAPI identity?

Goto: As part of the PFLAG San Gabriel Valley Asian Pacific Islander chapter, I’ve marched in the Golden Dragon Parade for the last several years in Chinatown as part of the Asian Pacific Islander Rainbow Coalition (ARC) contingent. ARC is a group of API LGBTQ-serving organizations that work to advance LGBTQ+ equality in the Asian Pacific Islander community and to support our LGBTQ+ friends and families through education, community organizing, and advocacy.

We have been so fortunate to help carry VROC’s (Viet Rainbow of Orange County) rainbow- and TGI-colored dragons in the parade. It’s an amazing feeling to see the faces of people in the crowd light up as we pass by and to hear them cheering and popping firecrackers. We frequently have people run into the street to take a picture with us. One of our founding PFLAG members is a crowd favorite with his “I Love My Gay Son” sign!

P.: We attend monthly API PFLAG meetings and visit with our community there.

Do: This year, I am honored to be helping co-produce HOTPOT’s Lunar New Year special event, Year of the Horse, with my dear friend and HOTPOT’s founder, Jordyn Sun. It will take place on Friday, February 20, at Apt 503. I will be one of the hosts, so feel free to stop by, say hi, and celebrate with us!

I will also be joining VietROC for their Tết festival in Orange County on February 13 and marching with the entire collective of QTAPI orgs at the Golden Dragon parade on February 21.

That said, every day is technically a celebration as a person existing at the intersection of being queer and Asian. Finding and welcoming other people in the queer Asian diaspora here in Southern California has helped me become more proud of who I am and where I belong!

Khommarath: Although I’m bisexual, I often move through the world as straight-passing because my spouse is a cis man and we’re raising our three visibly cis boys (as far as we know for now?). That visibility gap has pushed me to be intentional about how I honor my QTAPI identity — not just privately, but in ways that stay connected to community, culture, and the experiences that helped me understand who I am.

In fact, I didn’t fully embrace my bisexual identity until I started working as a community organizer at API Equality-LA. I had just graduated from LMU and was suddenly surrounded by queer and trans API individuals, leaders, and organizers who created a space where I felt safe, seen, and able to name parts of myself I had never had the language or community support to articulate. Being in that environment, being held by people who lived their truths so openly, helped me embrace mine. Those years were foundational. They shaped not only my politics and career but also my understanding of self, belonging, and pride.

Becoming a parent changed how I could show up in those spaces. I had to step back from the day-to-day organizing and intense participation to focus on the kiddos. But I’ve worked to make sure my QTAPI identity doesn’t fade just because my life looks “straight” from the outside. I celebrate in ways that fit the life I have now.

A lot of those celebrations look like family-centered rituals that connect my children to queer Asian American community spaces. For example, I’ve taken them (and intend to take them this year!) to the Golden Dragon Parade during Los Angeles Chinatown’s Lunar New Year celebration. These events include queer API groups marching or organizing, and being there with my children feels like bringing together the multiple communities that raised me and my identity. It’s a way of showing them that our cultures are vibrant and diverse, and that queer stories are part of our family’s and community’s fabric.

So, while I’m not celebrating in the same ways I did when I was younger (e.g., late-night meetings, rallies, coalition convenings, organizing 1:1 conversations, marches), I continue to celebrate my QTAPI identity through community events, storytelling, and the values that shaped me. I’m raising my children to understand, honor, and take pride in that part of me, too.

Wong: In 2006, a brand-new organization, API Equality-LA, mobilized the first LGBTQ+ contingent in the annual Lunar New Year parade in Los Angeles Chinatown. Over the years, our group grew into the largest contingent in the parade, drawing as many as 200 participants. This occurred against the backdrop of the fight for marriage equality and was a powerful symbol of growing support for LGBTQ+ visibility, inclusion, and civil rights in the API community. The annual tradition ended in 2021 because of the pandemic, and we have only revived our contingent during the past two years.

On a more personal note, over the years, I have hosted numerous birthday/theater parties at the East West Players, the largest and longest-running Asian American Theater in the nation, and a space that has nurtured many Asian LGBTQ+ performers, writers, directors and other artists.

How do you celebrate with your chosen family and/or your community?

Goto: The members of PFLAG SGV API are my chosen family and we usually pass out lucky red envelopes at our monthly support meeting prior to the Lunar New Year. We also table at as many festivals as we can to ensure our visibility in the API community and to distribute educational information, such as affirming language that families can use when their child shares their identity with them. We want to be a culturally respectful resource and provide non-judgmental support in a comfortable environment to API folks, no matter where they are along their journey.

P.: We enjoy food (often dim sum!) with our family and friends.

Do: I celebrate with my community and chosen family by getting politically engaged. Given fascism’s rise, it is crucial now more than ever to not only express our joy with chosen family as a form of resistance but to use that joy to fuel our community-building efforts. Whether that is organizing donations for mutual aid, sharing legal resources for our neighbors and friends, volunteering at a food distribution, or educating folks on how to take direct action, I see our collective efforts as a celebration in itself.

Wong: For most of my life, I would look forward to celebrating the Lunar New Year over a Chinese banquet with my family. Now that most members of my birth family have passed on, I have been gathering each year for a special meal with other API LGBTQ+ activists and allies. Coming together has been especially important given recent events (COVID, spikes in anti-Asian violence, horrific fires, ICE raids and attacks on trans rights) that have caused so much anxiety and suffering.

What are you hopeful for in the upcoming year of the Fire Horse?

Goto: I am hopeful that the beloved community coalitions that have come together over the last few years will continue to grow, gain momentum, and change the world!

P.: I hope for drastic change in the current trend toward negative legislation against trans persons. Trans people are just living their lives like the rest of us. Just because some are uncomfortable around them is not a reason to interfere with their lives. Rather, we should be getting to know those who are different and understanding each other better.

Do: Currently, I am working as the Community Mobilization Manager at the LA LGBT Center. I help activate community members to participate in a variety of actions ranging from phone banks to postcard actions, from door-to-door GOTV canvassing to legislative visits, and from rallying in the streets to making public comments with city and county officials.

The purpose of mobilizing is to make our voices heard, express urgency around a variety of LGBTQ+ issues, and spark transformative change. In our tumultuous present, I am hopeful that this year will give me the confidence to fuse my experience in organizing within LGBTQ+ spaces and my interests in other spaces that more directly address the wealth, equity, and access concerns of our broader community. In other words, I am hoping to harness the Fire Horse energy to strengthen existing and nascent solidarities across Los Angeles.

Khommarath: With the Fire Horse symbolizing bold movement, passion, and transformation, I’m hopeful for a year where I embrace more intentional risk-taking — not the reckless kind, but the kind that clears space for growth. I’ve spent so much of my adult life balancing responsibility, care, and community, and this year, I want to make room for creativity, curiosity, and the type of ambition that feels aligned rather than overwhelming.

I’m looking forward to exploring new ways of showing up in my communities and for my family and allowing myself to pursue things that energize me instead of defaulting to what feels safest or most expected. If the Fire Hose encourages anything, it’s to trust momentum when it arrives.

Immigrant communities, LGBTQ+ individuals, and communities of color are facing instability, fear, and targeted harm right now. It feels like every week brings another policy change, wave of rhetoric, or reminder of how urgently our communities need and deserve safety and dignity.

I’m hopeful for the capacity to stay GROUNDED — to remain connected to community struggles while being fully present with my children, modeling courage without losing softness. If the Fire Horse urges us toward boldness, then my hope is the channel that boldness into clarity and choosing when to act, when to rest, and how to hold both responsibility and joy at the same time.

Wong: As justice-loving people, it is easy to become paralyzed with anxiety and hopelessness given the enormity of the challenges we face today. But we have to remember: It is always darkest before the dawn. Courage does not mean lack of fear. It means acting decisively in spite of fear. May we find strength and comfort through collective action in the Year of the Horse.

Read more about each advocate and community worker by clicking the links above, and join them as they march at the upcoming 127th annual Golden Dragon Parade on Saturday, Feb. 21 from 1-4 p.m. in Los Angeles Chinatown. The Blade will be joining AJSOCAL on the route.

Jeffrey Deguia, LA Regional Policy Advocate at Asian Americans Advancing Justice SoCal, with contributions from LA Blade reporter Kristie Song, has curated this article.

Kristie Song is a California Local News Fellow placed with the Los Angeles Blade. The California Local News Fellowship is a state-funded initiative to support and strengthen local news reporting. Learn more about it at fellowships.journalism.berkeley.edu/cafellows.

Features

LGBTQ+ legal hero Jon Davidson hands civil rights torch to new generation

Davidson shares successful AIDS, GSA, and Asylum cases. As well as being in a polyamorous relationship.

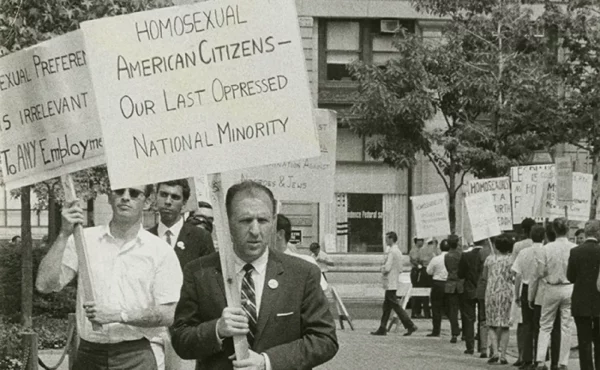

There are heroes among us in this violent struggle against the demented but planned tyranny of Donald Trump. In cities large and small and rural regions across America, including Los Angeles, “We the People” are standing up, walking out, marching, holding signs, and blowing whistles to bravely fight for our neighbors, our freedom, the US Constitution, and plain old fairness and human decency.

But for some of us, that fight has been existential for decades – as illustrated through the LGBTQ+ and other Smithsonian Institution historical exhibits Trump wants to hide and erase to make America way more White Supremacist again. (Please see this video to better understand our history and Trump’s promise to “decisively win the culture wars.”)

That’s why it feels like such a loss when a hero leaves or steps back, even for the most logical and human reasons.

Gay attorney Jon Davidson has been such a hero, a leader among the brightest of our warriors, using his humanity, skills, and acumen to fight against inculcated oppression and achieve real progress toward first-class citizenship.

“It’s impossible to describe how much our movement owes Jon Davidson,” Lambda Legal Executive Director Kevin Cathcart said in 2010 after Jon received the prestigious Dan Bradley Award, the National LGBT Bar Association’s highest honor.

Recently, Jon announced that he is retiring, which – given our tumultuous republic – seems like awful timing. “I’m 70 years old. I’ve been doing LGBTQ civil rights work for 40 years,” he shared during a comfortable Zoom interview on Jan. 28.

“I was a partner in a big Los Angeles law firm [Irell & Manella]; left to go to the ACLU of Southern California; then went to Lambda Legal, where I was for 22 years; then went to Freedom for All Americans, where I was doing lobbying trying to get the Equality Act passed; and then the national ACLU, where I’ve been for the last 4 years,” he says, pausing briefly.

“I really have started to feel like it’s time to let others lead – to get other voices out there and other ideas, especially from younger people, from trans and non-binary people, from people of color. And sometimes that means stepping aside,” Jon continues. “The thing that makes me feel okay about it is I’ve worked with a lot of those people, and I have tremendous confidence that they can do the best job that possibly can be done….None of us is irreplaceable.”

And, Jon adds, “even though I’m stepping down from paid positions, and I’m planning to take some time to take a rest and do the things that I never had time to do.… I doubt I’m really stepping away in the long term and that I will find other ways to contribute without being a full-time working civil rights lawyer.”

He’s keenly aware that resistance is needed.

“It’s a very scary time right now, no question. It’s probably the most frightening period of my long life,” Jon says. “Trump is an ego-driven, unbalanced, narcissist, erratic, mean-spirited, fungus, thin-skinned, vindictive, arrogant, corrupt….It’s hard to come up with enough adjectives. But mostly cruel, racist, sexist, transphobic wanna-be dictator….I guess the solace I take from the current period is the extent to which people are protesting.”

It’s not just the legal victories or the cases in which he was co-counsel or a thoughtful coach who will be missed. It’s the example Jon sets as a gay man. He emanates a deep secular/spiritual commitment to justice. He listens to everyone, regardless of class or position, embodying the old saying, “listening is an act of love.” And then he tries to find a way to help.

Jon didn’t just leave Irell & Manella, where he worked in the media and entertainment division after graduating from Stanford University, Yale Law School, and working as an attorney for eight years. He and his best friend, Sharon Hartmann, had convinced the partners to let them represent homeless people pro bono – a new and expensive concept at the time. At Jon’s retirement party, Hartmann said Jon built a team, and three years later, in 1987, they won an award for their pro bono work, and Jon, 29, made partner, which she called a “pretty good beginning.”

In fact, according to an April 7, 1987, LA Times feature entitled: “Repaying Society: Pro Bono: Renaissance in Legal Aid,” Jon “marshalled 34 lawyers, 46 secretaries and paralegals at Century City’s Irell & Manella to join poverty law firms in aiding the homeless on Los Angeles’ Skid Row.”

“Lawyers in private practice get to have a generally fortunate life. They are highly compensated, have a high status, and get a fair amount of deference and respect. Because of all those things, you really owe something,” Jon told The Times. “Part of it is, ‘Gee, this is something I really should be doing.’ But another thing is, I find it very satisfying to think there are certain people I can help.”

Jon left his Big Law Firm’s half-a-million-dollars-a-year salary to become Lesbian and Gay Rights Project Director at ACLU/SoCal under the extraordinary Ramona Ripston for $50,000. Coming out as a “gay rights activist” during Ronald Reagan’s second presidential term and the horrors of the Second Wave of AIDS was a big deal. So was his motivation.

“What initially got me into doing this work was the AIDS epidemic,” Jon tells me during our Zoom conversation. “I had quite a number of people I was close with who were very sick and who were dying. I felt like I was going to funerals every week. And so, even though I was in private law practice, I started doing pro bono work, which means ‘for the good of it’ – but it means ‘not paid,’ also.”

Jon says one of his most important cases was Chalk vs the Orange County Board of Education, a case that got national attention with a slew of other important gay and lesbian attorneys and a slew of amicus briefs, including one from California Attorney General John Van de Kamp.

Vincent Chalk was a beloved certified teacher and Regional Occupational Program coordinator for deaf students at University High and Venado Middle School. In February of 1987, after informing his supervisors that he had AIDS, Chalk was reassigned to an administrative position and barred from teaching. His claim of discrimination and request for an injunction were denied in the district court. Jon worked on his appeal, which they won. The Nov. 24, 1987, LA Times headline read: “AIDS Teacher Returns Amid Hugs, Smiles.”

“It was incredibly important to him to keep working because he found it very satisfying,” Jon says. “We won at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which governs California and other Western states, which established that people living with HIV are protected against discrimination….That started to turn [around] some of what had been people being turned away at restaurants and stores and not getting the medical care they needed. That felt very significant.”

Another “really important” issue was helping make Gay Straight Alliances possible.

“I did several cases, one in Salt Lake City and one in Orange County, in which we got it established that federal law requires schools to allow those clubs to meet if they allow other non-curricular clubs to meet on campus. That really seemed to me important in terms of making it possible for young people to feel like it was okay to be out, to establish connections with other LGBTQ people, and to start to do things to change attitudes at the high school level,” Jon says.

“And there are a number of those clubs right now that meet at the junior high school level. My partner was helping run such a program when he was earning his master’s in social work at a middle school for low-income, principally Latino students,” Jon continues. “So that seemed really important in turning things around.”

But, says Jon, the case that “touched me the most emotionally” was where I represented a man from Mexico who fled to the United States after he was threatened with his life by Mexican police, who assaulted him, stole his clothes, and left him in the middle of the desert. He came to the United States, sought asylum, and was initially denied asylum by an immigration judge who said, ‘Well, you don’t look gay to me. And so, you can go back to Mexico and just don’t make an issue of it, and you should be fine.’”

Jon appealed, and the case was sent back to the same judge, who changed his mind, “in part through the argument that, wait a minute – people who are persecuted in other countries for their religion or their politics are not told, ‘Oh, just don’t make an issue of it. Don’t let other people know.’ Those are grounds for asylum, not for denial of asylum.”

They got a new trial, and the judge granted asylum from the bench. “I walked out with my client, and he started crying and saying, ‘Wait. Does this mean that I get to stay? That I’m not going to be sent back?’ And it was just feeling so directly like you had really turned somebody’s life around. It felt an honor to be able to do that for someone.”

In 2017, Jon unexpectedly left his job as Legal Director at Lambda Legal, working closely with “work wife” Jenny Pizer. He went to Freedom for All Americans as their Chief Counsel, and later, he returned to the ACLU as Senior Counsel at the National ACLU LGBTQ & HIV Project.

Camilla Taylor, Deputy Legal Director for Litigation at Lambda Legal when Jon left, wrote an extraordinary tribute, with stories about and links to some of his hundreds of cases.

“If I had a nickel for every time I’ve witnessed JD up at ungodly hours to work, sifting through legal materials and strategizing with his colleagues about how to conquer a problem or action against our community, mastering every minute detail, we could shut down Lambda Legal, colonize Mars, and turn it into the queer utopia of everyone’s dreams.” Taylor wrote.

And that queer utopia includes individuals having the real freedom to determine how they wish to live their lives. Asked why Jon – who helped win marriage equality – has eschewed marriage for himself and his longtime domestic partner, psychotherapist Syd Peterson, Jon says simply: “We won the freedom to marry, not the obligation to marry. And for Syd and me, it was not the way we conceived of our relationship. We always had an open relationship, and certainly some people who are married have. But in more recent years, we’ve had an openly polyamorous relationship.”

But, since he co-drafted with Jenny Pitzer the California Comprehensive Domestic Partnership Law, “I felt some loyalty to it. So that was important to me.”

Jon says he was not open about his relationship with Syd because he anticipated that people would react badly, not understanding how being in a polyamorous relationship worked.

But at some point, the explainer-in-chief came to understand that that was being in the closet again. He felt some responsibility to let people know that it was okay and that it can work for some people, not for everyone. He says he just feels it’s important to fight against the lack of understanding and prejudice.

After giving tips on how to have such a successful, compatible, intergenerational relationship, Jon says, “I must admit – I never really thought we’d be together 21 years.”

“People need to figure out a way to survive,” Jon says in parting. “What I would add is for people not to give up hope – then the other side has surely won.”

Karen Ocamb is a veteran journalist and the former news editor for Frontiers Magazine and the Los Angeles Blade. This essay is cross-posted from her Substack LGBTQ+ Freedom Fighters. Please visit that cite to watch her in-depth video conversation with Jon Davidson about LGBTQ+ people and “strict scrutiny,” as well as the LAPD and other issues.

Features

Liliana T. Pérez-Palacios uplifts BIPOC, immigrant and queer rights with the L.A. Chargers

The L.A. Charger’s Sr. Director of Cultural Affairs talks coming out on national TV and making the local sports space more queer-inclusive.

At an L.A. Chargers game, football fanatics donning powder blue and gold jerseys can be heard crying out: “Bolt up!” as players on the field tackle, run, and charge with an electric energy. People grip their seats, their eyes darting back and forth as they witness a kind of alchemy happening in front of them.

In the midst of this exuberant chaos, Liliana T. Pérez-Palacios mingles with Chargers fans, greeting them excitedly as they celebrate a sport that brings them closer to the community around them. Pérez-Palacios is the team’s Senior Director of Cultural Affairs, and her role allows her to exercise her greatest passion: uniting the city’s diverse tapestry of people and providing them a space to discover joy and belonging.

Growing up: navigating her queerness and activism

Pérez-Palacios’ childhood flitted back and forth between fear and empowerment, the two emotions woven into the fabric of her adolescence. As a toddler, she immigrated from Mexico to the U.S. with her mother, eventually settling in the county’s Pico-Union neighborhood. She remembers the persistent, looming threat of immigration officials and the constant presence of poverty.

But, rather than embed these fears into shame, she learned to translate and transform her struggle into affirmation, power, and self-liberation. “I don’t live by what others think of [or] say about me,” Pérez-Palacios told the Blade. “I need to live my truth, and that’s something that was instilled in me since I was a kid.”

Self-possessed and strong, Pérez-Palacios wanted to turn that courage outward and support other marginalized community members seeking refuge and comfort. As a student at Cal State University, Northridge (CSUN), she developed her passion for social justice, serving in student groups like Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), Strong Queers United in Stopping Heterosexism (SQUISH), and Students Against Apartheid.

“[I was] a young Latino kid, wanting desperately to help people like me feel welcomed and at home,” said Pérez-Palacios, who was inspired by the bold, “in your face” approach that organizations like AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) adopted.

While her deep involvement with activism on campus led her away from her studies, this intense dedication to social justice led to a career in government service beginning in 1995. She served six Speakers for the California State Assembly as well as former California Governor Gray Davis.

Her civic engagement then caught the attention of Mayor Karen Bass in 2023, when she was appointed to be President of El Pueblo de Los Ángeles: a historic district that preserves the county’s Latine roots.

Coming out on national TV

Before these steps into local governance, Pérez-Palacios stepped into the limelight to advance queer visibility, even if it meant risking her closest relationships. She was in her early twenties when she heard that Cristina Saralegui, host of the major daytime Spanish-language talk show “El show de Cristina”, was making a tour stop in L.A. “No one was bigger than Cristina,” Pérez-Palacios recounted, who was determined to appear on the show to discuss the Latine LGBTQ+ community, and how it is impacted by suicidality.

Pérez-Palacios felt it was critical to discuss the mental health crisis amongst queer Latine youth, and came out as queer on the show in a brave display of personal solidarity. “I wanted to make sure that our community was never lost in translation,” she said. “Our lives are impacted by hate. I needed to put a face to it and say: Stop hurting us. We’re your family members too.”

She remembers her own family being shocked: there was the endless stream of opinions they threw at her for being openly queer. Her mother, whom she calls her best friend, “wasn’t ready for it” at the time. Still, Pérez-Palacios understood the gravity of the harm impacting LGBTQ+ people like herself, and this outweighed the potential rejection and ignorance she would receive in her own life.

Her mother came around soon after. “I’m her kid,” Pérez-Palacios said. “Her love is greater than anything else.”

Pérez-Palacios’ approach: creating an “orchestra” versus a “melting pot”

Pérez-Palacios credits her bravery to the importance of honoring the various identities that make up who she is. She fights for women, immigrants, Latine community members, and people impacted by poverty. “We’ve been trained to be ashamed,” Pérez-Palacios said. “[But] there’s no shame. If anything, there’s great pride there. We are communities of resilience and creation. When we don’t have anything, we create something.”

She leads with this ethos as she heads the development of cultural sensitivity and community-building at the L.A. Chargers. She is constantly looking for ways to bring different folks into the space and to help them embrace themselves in the celebration of the sport. The core of her work is being intentional about representing the rich cultural and social histories of L.A.’s eclectic communities: honoring their legacies of resistance, unity, and survival.

Today, she is excited about growing this “footprint” and bringing in more queer folks to the games. She hopes that by making this avenue of her professional career more inclusive, she can motivate the people around her to resist erasure and thrive together in each other’s unique origins and journeys.

“I hate the term, ‘melting pot.’ I do not want to be a melting pot,” Pérez-Palacios said. “I do not want you to be like me. I want us to be a beautiful orchestra. Together, through harmonizing, we create something amazing.”

Kristie Song is a California Local News Fellow placed with the Los Angeles Blade. The California Local News Fellowship is a state-funded initiative to support and strengthen local news reporting. Learn more about it at fellowships.journalism.berkeley.edu/cafellows.

Features

“We will get through all of this”: Culver City’s first LGBTQ+ Mayor discusses queer community and hope

Freddy Puza shares empowering words for queer youth and discusses his journey through local politics and advocacy.

On Dec. 8, Freddy Puza was elected to be Culver City’s mayor, after a decade of dedicated service to the City. His journey of advocacy began after he moved to Culver City in 2011, when he immediately dove into local social services programs and activism.

In 2016, he banded together with fellow residents to call on Culver City to become a sanctuary city and protect its immigrant community members. In March 2017, its city council adopted a resolution that solidified this call to action. The resolution prohibits law enforcement officials from sharing data and information with immigration authorities.

Puza also volunteered on Culver City’s homelessness and general plan advisory committees before he was elected to the city council in 2022. Now, as mayor, he hopes to deepen his connections with fellow residents and build upon what he’s learned from his journey so far. “Every year that I’ve been on council, I’ve grown into a new person,” Puza told the Blade. “I see how the city and community work in a different way.”

His down-to-earth leadership approach centers on listening and making people feel heard: a feeling he struggled to find during his own coming-of-age. “That’s a lot of the work that I think the city council is responsible for,” Puza said, “We set policy, but we also create and maintain community. I want to make sure that everyone is folded into the process: that it’s an inclusive city, and that people feel like they belong.”

The Blade sat down with Puza to discuss how he first formed queer community and how he hopes to set a precedent for the way local government can stand up for and protect its diverse constituents.

Isolation in faith: growing up without queer community

When Puza was five, his family relocated from the Windy City to the suburban bubble of Irvine, California: sweeping him up in a whirlwind of transition and change. His parents were devoutly Catholic and found solace with other Catholic families. Charity, volunteering, and local involvement were also always emphasized at home, so there was the constant presence of others.

But in the midst of this persistent chatter and noise, Puza was alone. “I grew up in a faith community that wasn’t open to being gay, so it was really challenging to move through that,” Puza told the Blade. “While my friends were doing professional development, I was doing personal development and coming to terms with who I was.”

Throughout Puza’s childhood, LGBTQ+ representation was minimal, if not outright negative. People around him weren’t coming out or having open conversations about their gender or sexuality. Marriage equality hadn’t yet passed, and he was not in proximity to queer scenes and leaders modeling unity and pride as he searched for belonging.

Puza remembers feeling “petrified” at the prospect of being out, and waited to do so in college. He also decided to leave his faith community and focus on his mental health and self-acceptance. This became his turning point. “I think, when you embrace your identity, ‘like attracts like,’” Puza said. “When I came out, all of a sudden, I started to see LGBTQ+ people amongst me and in my environment.”

Culver City was the “Goldilocks” perfect fit

Puza moved to L.A. in 2001, bouncing from Venice to Silver Lake to West Hollywood before landing in what feels like his best fit. “I do consider Culver City the ‘Goldilocks’ [of these neighborhoods]. It’s just right,” Puza said. “It’s just home.”

He first sought out the region for its diversity and vast, boundless sense of opportunity. He joined organizations that focused on LGBTQ+ civil rights and protections like the Human Rights Campaign and Equality California, meeting friends and mentors who brought him more deeply into the local queer community. “It was so essential to have those people that I’m still friends with, who I’m so close with,” Puza said. “All of that combined really got me involved.”

Why Culver City specifically? “It’s a small city relative to Los Angeles, but there’s so much opportunity to get involved with local change,” Puza told the Blade. “Culver City residents get to know their council members, and there’s a lot of activism going on [here].”

Advocating for unhoused residents: Puza’s first foray into local government

When Puza first began volunteering in direct services to support unhoused residents living in Skid Row, he learned about systemic and structural barriers and issues that perpetuate homelessness in the county. This is when he began to understand that problems and solutions are intertwined, and both begin at the local level.

Inspired by the everyday leaders around him, Puza jumped into action and joined Culver City’s homelessness committee in 2015. “Many times, people get frustrated with the government and don’t see it as something that can bring actual change,” Puza said. “So the fact that I was seeing all these community members in Culver City engaging in change and really caring about their neighbors: that compassion moved me.”

Today: Puza’s hopes and aspirations as mayor

Currently, Puza is working with fellow Culver City city officials to build a clear five-year Capital Improvement Plan. This includes setting targets for infrastructural improvement projects as well as increasing housing affordability and sustainability while generating more revenue.

Culver City’s population is expected to double in the next decade or two, and the City remains in a structural deficit. Puza hopes to strategize ways to streamline programs and processes while creating new systems that can get the City “back on track.”

He is also focused on protecting the safety of his community members as fears surrounding Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents are on the rise, especially with the recent ICE-related murders of Renee Nicole Good and Keith Porter. LGBTQ+ hate crimes are also on the rise, and queer rights are being targeted. Where the federal government fails, local governance and activism are revitalized, Puza says.

“People really do want to see the government deliver tangible things, and local government’s where that is at,” Puza told the Blade. “The federal government is not going to be helpful in the ways that are the most beneficial to community members. I believe in putting care for the individual, uplifting people, and giving them the tools to succeed: not punitive punishment.”

How can community members get involved?

There are many committees to join, as well as several open commission seats, according to Puza. He also encourages residents to directly get in touch with him or attend listening sessions where they can engage in dialogue with him and other community members.

“Those are really valuable opportunities to hear directly, and I want to always be listening to the community,” Puza said. “I want to make sure I’m in alignment with the community, and that the values that I set out with are still what the community and our residents want.”

And for queer youth and other LGBTQ+ people seeking belonging, the way he’d done years before, Puza offers this piece of advice:

“Find community and mentors who can help and guide you. It is a scary time, but I am a cynical optimist. So, I always believe, no matter what’s going on and how terrifying and horrible it is, we will get through all of this. You will make it. It will be tough, but have that strength inside to know yourself. I learned to love, accept and take care of myself, because we can’t give if we’re out of alignment. So really learn about yourself, and then go out there and don’t be afraid.”

Kristie Song is a California Local News Fellow placed with the Los Angeles Blade. The California Local News Fellowship is a state-funded initiative to support and strengthen local news reporting. Learn more about it at fellowships.journalism.berkeley.edu/cafellows.

Features

“We deserve to have a future here”: How we can support queer AAPI communities in 2026

This week, the Blade sat down with AAPI Queer Joy’s leader Jeff Deguia to reflect on his activism goals in the new year.

AAPI Queer Joy is a queer-led and focused coalition formed by Asian Americans Advancing Justice Southern California (AJSOCAL) policy advocate Jeff Deguia. In a previous feature, the Blade learned more about Deguia’s activism journey, from his Filipino American upbringing in Chicago to his exuberant, inclusive leadership in Los Angeles. We also interviewed Lan Le, a fellow AJSOCAL policy advocate and AAPI Queer Joy leader who is passionate about supporting other queer refugees and domestic violence survivors.

The coalition currently includes six grassroots civil rights organizations, including: AJSOCAL, Viet Rainbow of Orange County (VROC), the Bay-Area based Lavender Phoenix, Search to Involve Pilipino Americans (SIPA), Moonbow, and Hmong Innovating Politics (HIP).

AAPI Queer Joy formed in 2024, and that initial year was focused on increasing visibility and establishing the coalition’s existence. Last year, in 2025, AAPI Queer Joy began to amp up advocacy efforts, and each organization involved worked together to put together the coalition’s first-ever bill package.

This package included three bills: AB 1487, AB 678, and SB 418, focusing on expanding funding opportunities for two-spirit community members, creating an LGBTQ+ inclusive council on homelessness, and building stronger access to gender affirming care, respectively. The Blade reported on these bills in October.

Deguia found it fulfilling to dive into LGBTQ+ focused legislation and support his coalition members in bringing their advocacy work to the state level. Most of these partner organizations, like Viet Rainbow of Orange County, are hyper-local, aiming their on-the-ground efforts to specific regions.

They’re also small, with teams that often cap out at around 10 staff members. “They’re wearing a lot of hats,” Deguia told the Blade. “So for them to add to their capacity to do advocacy work and understand the importance: I’m grateful to them.”

This week, the Blade sat down with Deguia to reflect on AAPI Queer Joy’s growth in 2025, the challenges they faced, and how he hopes to grow the coalition in 2026.

Challenges AAPI Queer Joy faced in 2025

Deguia explained to the Blade that language access and cultural bridging can be difficult within the AAPI community, especially when it comes to having conversations around being queer with immigrant family members. “[For] certain LGBTQ+ vocabulary, there are no translations in AAPI languages sometimes,” Deguia said.

Tools like Google Translate have their limitations and don’t include the necessary cultural context needed to have sensitive discussions about identity and relationship-building. This often means staff members have to do additional work to translate certain terms and then ask their partner organizations for further support.

“We want to make sure that the LGBTQ+ community will feel understood, but also that their loved ones, their allies, parents, grandparents, and other folks will be like: Oh, this helps me understand what this word would be in language,” Deguia said. “So that’s definitely tough.”

Deguia and this reporter also discussed the concept of being “out” and how that experience is complicated for diasporic people who both live in the West and also belong to a different culture. In some Asian countries, where communal unity is valued over individualistic pride, being “out” should be treated with contextual nuance. Whether or not someone feels comfortable being out, Deguia hopes that community members make their choice through empowerment rather than shame or pressure.

“For AAPI people who are born here or raised here when they’re really young, [the question can be]: How do we make our own way and make sure that we’re living on our terms?,” said Deguia.

“Being out [can be a] proud moment, but understanding the cultural parts of being AAPI and not necessarily being out also has its own importance in the community. And saying that not being out is wrong, or having these really strong opinions on it, is unfair. That’s nuance and lived experience. It’s about cultural balance.”

How does AAPI Queer Joy hope to grow in 2026?

Deguia points to three main goals in this new year: seeking stories and inspiration from community elders, expanding the coalition, and organizing an AAPI Queer Joy event in L.A.

He hopes to lean on elders to better understand the lineage of activism before him, and to carve out a path built on history and imagination. While these elders had no “blueprint” of their own, Deguia hopes to hear their stories as they move towards a shared, intergenerational goal together.

“I’m building upon what has been done before me,” Deguia said. “I think about the folks who had everything set up against them, who believed: ‘I’m trying to get easier for someone after me.’ I’ve gotta understand my history so I can make a better path forward for [those] after me.”

When it comes to growing the coalition, Deguia has inclusivity at the forefront of his mind. He wants to include more partner organizations from the South Asian and Pacific Islander communities, which are often underrepresented in broader conversations around being AAPI.

“I don’t think I can call it AAPI Queer Joy without having reps from every part of that beautiful community,” Deguia said. “I [also] want to make sure that the whole state’s being represented well, like central California, SoCal, NorCal. There are communities that have a voice and want to show up and be in these kinds of conversations.”

To activate these communities, AAPI Queer Joy puts on their annual Jade Jubilee: an event that is both celebratory and productive when it comes to what the coalition has achieved and how they hope to strengthen its advocacy work. Jade Jubilee was organized in Sacramento last year, and Deguia wants to bring something on this scale to L.A. too.

“The QTAPI community in L.A. and Orange County is really rich and diverse,” Deguia said. “I want to showcase that there’s an organization based in L.A. here that is doing this work. I want to engage the community here more.” When thinking about accessibility and engagement, Deguia sees these potential local events as a chance to give friends and community members the tools, knowledge, and joy needed to move forward together.

How can we support AAPI Queer Joy?

Small actions can have large impacts. Deguia mentions the power of sharing the coalition’s social media posts, which often highlight their legislative campaigns and efforts, as well as supporting its partner organizations. There are grassroots groups out there who are connecting like-minded people: seek them out as a first step.

From there, you can learn about attending events and rallies, and understand the importance of individual efforts like calling representatives (which can also be done in community!) to voice your concerns and perspectives. Many of these local organizations provide scripts and workshops to ease fears and anxieties around these actions.

And, whenever possible, don’t turn away. It is demoralizing to see the constant threats to LGBTQ+ safety and rights, and the constant attempts to self-soothe are exhausting. But now, more than ever, it is necessary to understand what is happening around us and how we can empower one another with support, knowledge, and resistance. “If we turn our backs completely, forget and just live in our privilege, one day we’re gonna wake up, and things will be gone,” Deguia said.

Deguia: Being resilient and brave is something I wish we didn’t have to do all the time as queer folks, but [this moment] is asking for that. In a country and administration that’s telling us that we don’t have a right to exist, we have to be brave and tell them and show them that we deserve to be here like everybody else.

At the core of all the pain and all the fear, the core in our heart [has to be]: “I deserve to be here. I deserve to have a future here. My friends deserve to be here. Trans folks deserve to be here. I will do what I can in my power to make sure that we exist and we can live lives that are full of thriving and opportunity. Fighting and believing in our existence and our futures have to be at the core of how we live every day.

Kristie Song is a California Local News Fellow placed with the Los Angeles Blade. The California Local News Fellowship is a state-funded initiative to support and strengthen local news reporting. Learn more about it at fellowships.journalism.berkeley.edu/cafellows.

Features

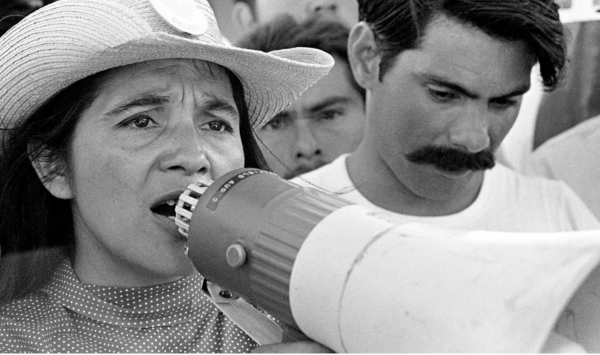

Legendary organizing activist Dolores Huerta, 95, rides in AHF’s ‘Food for Health’ Rose Parade float

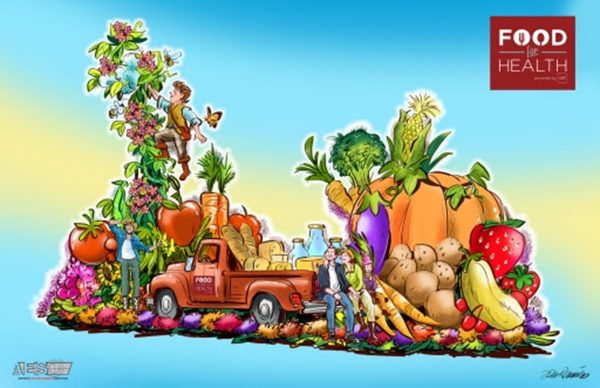

This year’s float honors AHF’s food banks, free farmers’ markets, veterans’ food programs, and massive SoCal wildfire food relief efforts for evacuees and first responders

Need some inspiration for 2026? Fix your gaze on the Pasadena Tournament of Roses this Jan.1 to find the amazing, legendary civil rights and union activist Dolores Huerta riding on AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s “Food for Health” float in the Rose Parade – an incredibly fitting community tribute to the 95-year-old co-founder of the National Farm Workers Association (now United Farm Workers) with the late Cesar Chavez.

The AHF float spotlights the organization’s national initiative to combat hunger and food insecurity by providing nutritious groceries – including produce, bread, dairy, and other staples– to families and individuals in need. Their program is illustrated through “a vibrant ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ motif, symbolizing growth, nourishment, and the power of community collaboration,” with oversized pumpkins, carrots, eggplants, and strawberries “representing the abundance that can bloom when people work together,” KTLA noted in a recent story. An overflowing farmer’s market truck is a tribute to “AHF’s volunteers and partners who served more than 75,000 meals to wildfire evacuees and first responders earlier this year.” (Click here to see KTLA’s report on the AHF float.) AHF reports that by the end of 2025, its Food for Health program “will have served over half a million people across the country with weekly groceries.”

While AHF has a reputation for illustrating significant issues through the Rose Parade – starting in 2012 with their float tribute to “Elizabeth Taylor: Our AIDS Champion” – this year’s focus on food insecurity and the possibility of hope through community collaboration is particularly significant.