History

Darnell Moore on feeling this moment’s ‘storm within a storm’

Presidents can set or erode national standards. Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction reversed freedoms for formerly enslaved people after the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. Woodrow Wilson’s praise for D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” rejuvenated the Ku Klux Klan and legitimized terrorist white supremacy, Jim Crow laws, and lynching as the evil banality of systemic racism.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, on the other hand, refuted his southern cronies, signed two landmark civil rights bills and announced “We Shall Overcome” to a shocked Congress.

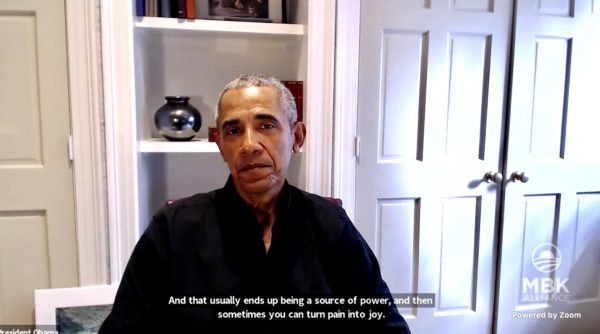

Today, there could not be a more profound moral and policy distinction between Donald Trump’s callous and cruel promotion of white supremacy and the fake machismo it inspires, and the smart, heartfelt vulnerabilities evinced by Barack Obama, who lifts up caring and empathy as character strengths to be shared communally.

Obama also thinks that inculcated toxic masculinity can be deadly in depriving Black men and boys of their human right to feel.

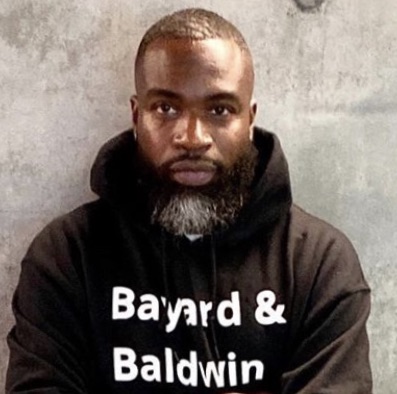

Eliciting Obama’s vulnerability during a virtual town hall was queer activist and intellect Darnell Moore, author of “No Ashes in the Fire: Coming of Age Black & Free in America,” a 2018 New York Times Notable Book. Acclaimed trans writer Janet Mock has said of him: “Darnell Moore is one of the most influential black writers and thinkers of our time.”

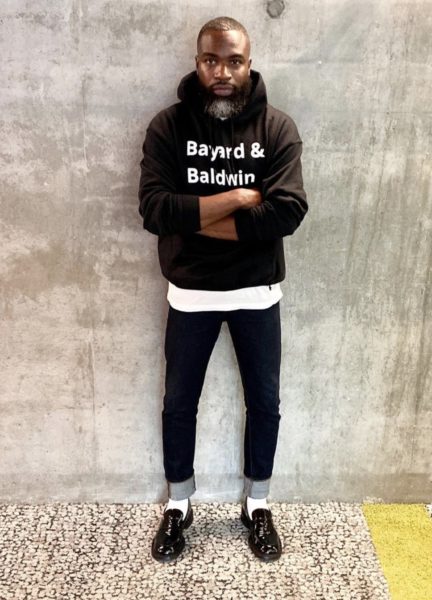

Moore, a writer-in-residence at the Center on African American Religion, Sexual Politics and Social Justice at Columbia University, facilitated the June 5 intergenerational conversation sponsored by the Obama Foundation’s My Brother’s Keeper Alliance.

He urged the panel on “Mental Health and Wellness in a Racism Pandemic” — which also included civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis, Bryan Stevenson, executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, Leon Ford, writer and survivor of police brutality Jr., and youth leader LeQuan Muhammad — to open up about the anguish of systemic racism felt by Black men and boys, especially in light of the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and “the loss of far too many Black lives to list.”

“This conversation is meant to be intimate, communal and also a space for Black men, men of color to experience and model vulnerability,” Moore said. This moment is an “unprecedented time” of global pandemic and racial violence. “We are in what might be best described as a ‘storm within a storm.’ So many of us are not OK.”

Obama shared how he was bereft of words in 2015 after a white supremacist killed nine churchgoers during Bible study at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C. He felt his words after other mass shootings, including Sandy Hook, had not made an impact. But when the churchgoers forgave “this misguided hateful young man,” Obama focused on their grace.

“It was their strength, not my strength that I was relying on. It was their grace that bathed me in grace,” Obama said.

“Usually, when I’m overwhelmed, discouraged angry, depressed, what has lifted me up is when I don’t feel alone and I can connect what is going on with me to what is going on with us,” he continued. “It is a profound thing when you are able to recognize that whatever is happening to you, whatever you’re going through, it’s not just about you. And you’re not the only one going through it and that usually ends up being a source of power and sometimes you can turn pain into joy as a consequence.”

Moore noted that “community healing requires community. Community requires all of us,” adding that “our idea of community has to be so wide, so expansive.” And that means that “all Black lives matter, whether those Black folks show up as straight or LGBT.”

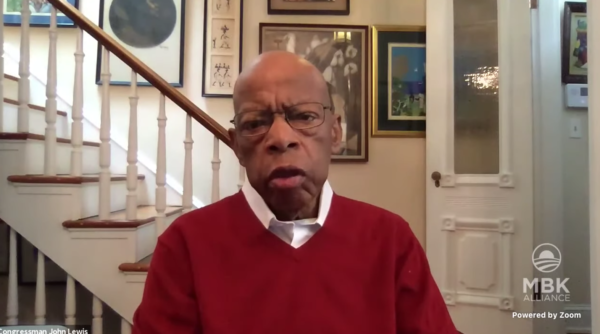

Lewis, who has been battling Stage 4 pancreatic cancer, said he’s been incredibly inspired by the young marchers.

Lewis was 25 on March 7, 1965, when he helped lead a march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama to commemorate Jimmie Lee Jackson, fatally shot 17 days earlier by a white state trooper as Jackson protected his mother during a civil rights protest.

On what became known as “Bloody Sunday,” white police charged the 600 demonstrators on horseback and on foot, wildly swinging their billy clubs. Police cracked Lewis’ skull during his beating, captured by TV news cameras.

“It’s all going to work out. But we must help it work out. We must continue to be bold, brave, courageous, push and pull, ’til we redeem the soul of America and move closer to a community at peace with itself,” Lewis, a longtime LGBTQ ally, told Moore and the panelists. “But no one, no one, will be left out or left behind because of race or color or nationality.”

Moore agrees. “I’m energized by the groundswell of people who are responding in this moment,” Moore told the Los Angeles Blade by phone on Sunday, June 7. “I’ve been describing it as a ‘storm within a storm.’ We are at once within the context of a pandemic that has devastated, in very real ways, people’s lives the way that we are typically a community.

“But also,” he continues, “I think it’s important to think about the ways the pandemic, particularly within the context of the US, revealed what had already been — and that is structural inequities like anti-Black racism, the class division, and also the impact of economic disparity on women of color and girls of color and trans folks.”

All the old structural inequities have been exacerbated.

“Even in a pandemic, we had Black and LatinX and Native American folk who were disproportionately testing positive and also dying,” he says. “And in the midst of all of that, we have continued forms of racial violence — both at the hands of law enforcement and at the hand of white vigilantes — that ended in the deaths of Black people, like Ahmaud Aubrey, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor,” (for whom they held a moment of silence on what would have been her 27th birthday).

Moore also feels the pressure of being LGBTQ.

“For me, to be Black and queer within the context of this moment is to really always be sort of out of breath,” Moore says. “To see people in this way, take to the streets, to speak back the power, to express themselves, to organize, both on the ground and virtually, to contend with all of the things that are not right, the racism that we breathe like air within the concept of the country, the white supremacist ideology. And not ideologies. But also laws and regulations and policies, and the way that we have resourced government instrumentalities, like law enforcement, in ways that have done harm to Black communities.

“So, in some ways, I have been overwhelmed —overwhelmed by the incessant deaths that we are confronted with, murders and killings. Overwhelmed by having to watch videos of folk being killed by law enforcement or chased down by white vigilantes. Tired and exhausted, emotionally and psychically exhausted of having to see that. And also exhausted because it often takes videos, evidence for many folks who are not directly impacted — in this case, for a lot of white folks — to even see this as a reality that they should also be linking themselves to, fighting on behalf of.”

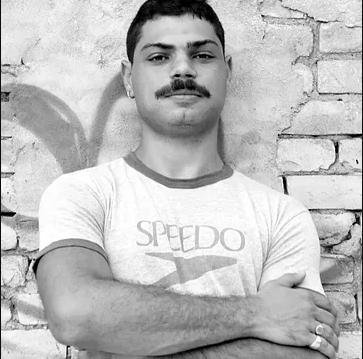

Darnell Moore (Photo by Paul Stewart Jr.

But, Moore says, “empathy has its limits. We should never have to list a litany of black deaths in order for people to feel.”

Moore feels energized but “I’m also feeling the complicated feelings of what it means to be in a moment that feels like a time loop. These iterations are part of a long struggle for black freedom that didn’t just start today. It didn’t start at Black Lives Matter, with the movement for Black lives of 2014. It didn’t start with Trayvon [Martin].

“It started the moment Black people were brought here as enslaved people — and that fight has been perpetual,” Moore says. “We shouldn’t have to fight so damn hard for a freedom that this country says it puts its belief in.”

Moore says he’s energized by people speaking up.

“And I’m energized by the folk who are committing to a process of self-reckoning — a practice of self-reflective analysis that is not only around analyzing all of the systems that we need to contend with, but folk who are saying, ‘Actually, let me take this mirror and turn it on itself as a white person. Let me examine the extent that I have put my face in whiteness. Let me think about the ways that I have —as non-queer people, right? — let me think about the ways that I have breathed this air of queer and homo antagonism and trans antagonism so cavalierly,’” he says.

“What I love to see is when people get galvanized and pulled into movements like this and are able to assess themselves and do the work on self as a part of also transforming our world,” says Moore.

“There’s a way, that in this country, to seem progressive, one of the formulas for that is to always be able to name whose feet are on our neck, right? We are good at naming the ways that we might be experiencing harm or impacted by oppression,” he continues.

“But the work in this moment is about naming the necks that our feet are on. And after having done that work, taking your feet off. That to me is what equity looks like,” says Moore.

Moore is now interested “in folk talking less, not pandering to the moment, not doing public relations stuff by putting up a Black Lives Matter tag or a black box in a Instagram post, or even naming it,” he says.

“We’ve got to go beyond the words. We need action. And that action is about changing systems — but it’s also changing a self. And when I can begin to see that, that’s when I think I can be a bit more hopeful.”

How would you see that manifested?

“I think there are a lot of ways that that can be manifested, right?

I would love to see white folk in conversation with other white folk. By the way, this happened. There are white folk who are anti-racist, who literally are in the work of undoing racism. And part of that work looked like not really putting the onus, putting the burden on the impacted person. That is, in this case, we’re talking about the matter of black lives.

Black folk shouldn’t have to do the work of educating white masses out of their racism, right? It means in the same way that it is not the work of queer and trans and nonbinary folk, LGBTQI folk, to do the work for straight folk. It is not our job to teach straight folk how not to be homophobic, right?

It’s not the job of women, whether they’re cisgender or transgender woman, to teach men how not to do the things to them that harm them. It is not the job of those groups, of those people, who are the directly impacted, who are impacted by structural and material inequity, right, and ideological biases and everything else, to do the work of teaching the other.

So that work, to me, looks like those who sit closest to the axis of power, to power, to begin to confront themselves and each other, to do that work.

And that, to me, it gets to this point — there’s work to happen at multiple levels. Yes, we need policy change. Absolutely, policy change, we need changes in law, we need changes in practices.

The movement for black lives has a call to confront police as part of its larger framework of abolitionism. I’m thinking about a scholar, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who defined abolition as not just a removal of the bad things, structures, institutions, practices, instrumentalities, that don’t work. It’s not just about removing those things, it’s about imagining what needs to go in its place. Now, imagine if we took that framework and applied that to our ways of thinking, our ways of being in the world. Let’s apply to abolition that sort of framework to white supremacy.

It means that you absolutely have to work on systems of inequity, but it also means you’ve got to work on abolishing those thoughts, working on deconstructing those ideas that we hold on to, working on analyzing and thinking about how we, ourselves, might also be complicit in some of these various things that are harmful and impactful to the other.

I guess, a perfect way to give an example of that is: I am a black queer man. I am cisgender. Yet I name myself a pro feminist. I am in community and solidarity with feminists, with women, with girls, with nonbinary folk, with femmes. I’m in solidarity. It is my job to do the work of unlearning all that I have been taught to believe about maleness and masculinity and all of its feign and superiority.

I had to, every day, unlearn a lie that had been taught to me about who I am as a man, a cisgender man, in a world. That is my work. That type of work is mine. I have to do that on me. And I don’t have to rely on you, on a woman, to do that for me.

It’s the same work that white people can do with regard to white racial supremacy.

I think it’s just as important as structural change. People are the ones who create policies, right? We are the ones that are creating law, we are the ones creating communal practices. And, if we’re going to create a better world, a more liberatory world, it requires that the person who’s doing that creating free themselves first, free their minds and their spirits first, so that they can then go out there and do the work, the structural work in a world…

Solidarities are critical. We live in a world where part of my own growth was, because I was in community with black lesbian feminists, like Cheryl Clark, as one example, poet and activist and scholar, who through our friendship, I learned so much about not only her lived experience as a black woman, who is also a lesbian, who came up in a very hyper-patriarchal type of movement. But in that, I was also learning about myself.

So the thing is, we can be in community with folk who are “other” without putting the responsibility on them to teach us, partly because look, I read books. Let’s start there, right?…

The second book that I’m working on is tentatively titled, “Unbecoming: Visions Beyond the Limits of Manhood.”…I think the way that you get free is unbecoming, unlearning.

It isn’t that I need to become a better man, right, I need to actually fail at, give the middle finger to, not acquiesce to, all of the things that society has told me that I need to be in order to be seen and understood as a man.

For me, it’s not even me becoming a better man, what would it mean for me to become a better human person?… Humanity has been a category that has been denied to black people within the concepts of the US. This is a country, within a very short history, that has literally documented that black folk were three-fifths of a human person, that they were property. So it makes sense that folks would want to hold on tightly to the category of manhood.

But if we took these categories away, what does it mean to be a person who is living justly and just community with people, a person who is open to equity and making sure that equitable practices are part of our everyday life? Those are questions that any of us can ask. And it doesn’t require someone who is impacted by the thing that we might be complicit in to teach them about that.

I remember going to a protest when I was living in New York City. And it was a protest in response to, I don’t know, there’ve been so many black local men killed at the hands of police. I can’t even remember the particular protest I was going to…. I’m on the A train and I’m walking by people going to this protest to say ‘Black Lives Matter’ and I remember having this moment where I’m thinking, ‘How radical is it that I’m walking to a protest to proclaim Black Lives Matter, to lift my fist up — and I haven’t stopped to speak, to look into the eye, to offer a gesture of love and care, to any of the people that I came upon before I got to the protest?’

And for me, that illuminates the disconnect between what we understand to be performative radical action and the everyday ways of life. It is not just enough for me to be out there with my fist up if I have not put into practice love, right, like community?

So, what did that look like? It looks like yesterday, my neighbor who came by, who is white, from Israel. Sat out on my porch and we talked for three hours. It looks like his wife saying, ‘How are y’all doing?’ Recognizing that it’s a lot going… I was also really, really hyped because they were like, ‘I love what’s happening. Burn it down.’ But that idea of them not waiting for us, my partner and I, my black partner — they came to us and asked how we’re doing, instigated a conversation that wasn’t centering themselves, but really was seeking to understand.

Let’s just speak. If you’re white and we’re protesting in this moment, I love that. But if your friendship circle is still homogenous with people that look just like you, if you’re at workplaces and you’re sitting down at lunch or Zooms or whatever, and you look at the grid and see that they’re all white faces there — if we are not responding to those types of everyday mundane, common ways of being, then the protests fall short.

It becomes something other than radical. It becomes performative because you have to embody the practice every single day. Every single day. It looks like me getting on the call with coworkers, like last week in the middle of all of the energy and the emotions that were present, and coworkers saying, ‘Hey, before we go forward, do you have the capacity to do this meeting right now? We can cancel if you need to.’

When I meant leaning into our humanity, that’s what that looks like. Yeah, the grand gestures are fine, your Black Lives Matter poster, fine. All of this stuff is totally fine. We’re having this conversation in the middle of Pride month. And I said to some folks, when the AME shooting, Dylan Roof, murdered those nine parishioners and stuff, in South Carolina, I remember it was really hard for me to do any Pride-related activities.

Well, let’s be clear: if I’m going to say LGBT, but often as the case, it’s really a lot of men, gay men and mainstream organizations, gay white men, there was a silence present within the Pride, pride.com space.

And I feel the same way now where it’s like, even as a black, queer person, I am always black and queer always, at once. And we lift up the Pride flag of radicalism. One, a pride that comes off the heels of radical movement. But lift that up without attending to the reality that some among the LGBTQI are also black, then we do ourselves a disservice. So even in a moment like this, for Pride, I’m like Pride?

This is an opportunity for queer and trans and LGBTQI folk to be in solidarity, to decentral whiteness within the Pride movement and say, ‘We understand the radical roots of LGBTQI movement, right? We’re going to use this as an opportunity to flip things on its head and tend to the folk who need their voices elevated in this moment.

I mean, there are everyday ways of being, that each of us, as individuals, can engage with one another as neighbors. And by neighbors, I don’t just mean the people that you live next door to, right, but as human persons. And then there are also ways that we can do this structurally within our movement spaces that challenge us to make sure that we are always leaning into empathy, not the type of empathy that comes and goes after the next news cycle, but the type of empathy that says, ‘We see you, we care, and we’re going to show up for the folks that are being directly impacted by structural violence in this moment.’

The reason why we’re even able to be in the streets right now and to call for a type of justice, however people imagine that to be, in response to George Floyd, there was video evidence, right? It’s possible — and we know this is true — that because of the lack of video evidence, people have been murdered. And in the case of the law enforcement, law enforcement has gotten off with impunity. So, video evidence is important.

And also, because of that, I think it’s important for the purposes of correcting, or at least responding to, historical amnesia within the concept of the US where we like to not be honest about the violence of racism that has impacted black people, indigenous people, in this country and many others.

Those archival…it’s our private pain, really, are so critically important. But the rub and I think it’s important to name it is the fact that we have to have this archive in the first place for folks to understand or to believe is itself part of the problem.

The archive is not necessarily the problem. It’s the fact that you need it. It’s the fact that we had to literally show George Floyd’s last breath on video, and possibly over and over again, because somebody might be looking in to figure out, ‘Well, did he do something wrong here?’

We saw Emmett Till’s photo, and we know that that photo did not stop folks from buying into white supremacy. We saw, ‘I can’t breath’ happen with Eric Garner. And still, with that archive, we have people going out there saying, ‘Well, what did he do to deserve that?’

So the archive is important and that evidence is important. And it’s also important to remind folk that the fact that we’ve got to give you this over and over and over again, that’s the problem.

And the refusal to believe when it’s right in front of our face.

Top Darnell Moore photo by Paul Stewart

Here’s Moore moderating the Obama Foundation panel, followed by a video of Moore discussing this theory of abolition.

Arts & Entertainment

A Night of legacy, love, and liberation: Inside the 2025 April Fool’s Ball

Ballroom culture continues to thrive among Black and Latin American queer culture

Late last month, the West Coast Ballroom Community lit up Los Angeles for one of the most anticipated events of the year — the April Fool’s Ball — produced by Legendary Father Markus Tisci. Now a staple of the L.A Ballroom calendar, the annual event is known not only for its high-caliber talent and unforgettable battles but for the legacy, love and chosen family it uplifts.

But let’s be clear: when we talk about “Ballroom,” we’re not talking about waltzing under chandeliers, we’re talking about the underground queer subculture birthed from the genius and resistance of Black and Latin American queer people — especially trans women and drag queens — in New York City.

Ballroom has since shaped and influenced mainstream culture, as seen in moments like Madonna’s “Vogue,” Beyoncé’s “Renaissance” and shows like “Pose” and “Legendary.” Today, that legacy continues to evolve and flourish far beyond New York, thriving in cities across the West Coast and beyond.

Markus Tisci has been a part of that movement for over 18 years and his roots trace back to the House of Rodeo — one of the West Coast’s most iconic original houses. In 2018, he founded the April Fool’s Ball with a simple but powerful goal: to bring laughter and creativity back into a space that was becoming, ‘a bit too serious.’ Conceived, produced and largely self-funded by Tisci, the ball is still known for its playful, pop culture — inspired categories that encourage imagination and joy.

Highlight the reel from the night of the House of Gorgeous Gucci.

This year’s April Fool’s Ball was filled with emotion, celebration, and remembrance. Just a few days earlier, the community laid Icon Devine to rest. The passing of the Queen of the West Coast Ballroom Scene and Legendary Mother of the West Coast Chapter of the House of Gorgeous Gucci left a deep void. For Ballroom Icon Jack Mizrahi, one of the night’s emcees and a foundational figure in Ballroom culture — as well as the father and founder of the House of Gorgeous Gucci — the event became a moment of both grief and healing.

“Seeing my house assembled, having each other to lean on, and the love we got from the whole West Coast Ballroom scene — it meant everything,” he shared.

In a powerful moment during the Legends, Statements and Stars (LSS) call — a time at the beginning of every ball when individuals are recognized and honored for their influence and impact — Mizrahi invited all trans women, whether they were walking or not — to step forward.

“Let the world know they deserve to be safe, protected, loved, and respected,” Mizrahi declared.

As the crowd cheered, those women (including the author) took their place with pride, their presence a radiant tribute to Icon Devine’s legacy and the enduring spirit of trans brilliance that Ballroom has always celebrated.

Fem Queen Parade at April Fools Ball 2025

The crowd erupted during the “Overall Face” final battle, where Jozea Flores — an up-and-coming Ballroom Legend in the House of Gorgeous Gucci — took home the grand prize of $1,000. In the “Face” category, contestants are judged on their natural beauty, expression, and how well they can ‘sell’ their face.

“When two stunning faces battle, you have to see who’s selling it more. That night, I sold it.” For Jozea, it’s about more than cash or trophies, though. “The energy from the crowd is my favorite part,” he shared. His message to the queer community: “Keep being true to yourself. Live boldly. Live loud.”

Royal Telfar Tisci, a fierce presence in “Gender Non-Conforming Runway,” also left their mark.

“It felt like old-school Ballroom energy,” they shared. “It was my first time walking at 5 a.m. — wild, but so worth it.” Royal walked with pride, earning their 10s and winning three battles.

“Runway is where we should shine. And that night, I did. But it raises the question — why aren’t GNC folks being included more consistently?”

As both a performer and advocate, Royal knows what’s at stake.

“There are forces trying to erase queer people, Ballroom, and especially the trans women who built it. We have to stay resilient, come together, and stay proud.”

Though Royal never lost to a competitor, the final battle and $3,000 grand prize was won by their chosen family member, Legendary Envy Tisci, the Bay Area Father of the House of Tisci.

“The night was long, but I enjoyed creating moments,” said Tisci. “I don’t get wrapped up in winning — I focus on the memories.”

Even as the night stretched into the early morning, the energy never faded. Destiny Ninja, Princess of the West Coast Chapter of the Iconic House of Ninja, delivered a voguing performance that closed the night with intention. She won “Women’s Performance” and after winning three battles, made it to the final battle in “Overall Performance.”

“I had so much to express and the runway was the perfect place to release it all,” she said.

The April Fool’s Ball continues to hold space for legacy and liberation. In the wake of Devine’s passing, the night became a reminder of the community’s strength.

“[Tisci] deals with applause, scrutiny and everything in between,” said Mizrahi. “And he still shows up. We need to stay united. Devine fought hard for visibility and respect. The West Coast needs to honor that — not with division, but with love.”

Tisci reflected on the night.

“Devine was a trailblazer—our Queen of the West Coast. Her impact still shapes the next generation. She’ll always be in our hearts. Tonight was about growth, legacy, and keeping the energy alive.”With the next major event — The Legacy Ball scheduled for June 1 — the community is already looking ahead. In a time of uncertainty and political hostility, the April Fool’s Ball re-affirmed what Ballroom has always been: not just a scene but a sanctuary. A home. A lifeline.

History

Los Angeles Blade celebrates 8 years!

SoCal’s LGBTQ+ news source celebrates 8 years of news catered to the LGBTQ+ community in print and online

March 24th marks the 8th anniversary of our newspaper. Even as the political attack on the queer community wages on, we continue the legacy that Los Angeles Blade founder Troy Master began. Our promise to the LGBTQ community is to continue to bring you the latest in political, social, entertainment, nightlife, and activist news, for and by the community. Our voice will stay steady and strong and remain the leading news source for and by the queer community.

In addition to bringing you the latest in news, we will continue to highlight leaders from the community from the social and political world. Our initiative to build bridges with the Latinx community continues through our close relationship with CALÓ NEWS with weekly reporting on issues that affect both groups. This year we will be kicking off Pride season with the return of our Best in LA Awards show, coming back bigger and better than ever.

Among our new initiatives this year, we are returning to the community with a series of free panels and discussions, covering important issues that are affecting the community, queer and beyond. We will be working with our power partners from the non-profit world, government offices, and social organizations to remain active and visible in an effective way.

We are also growing our local writing team to better reflect the diversity that exists around us.

We continue to be Los Angeles’ only LGBTQ bi-weekly newspaper and the City’s largest, most frequently distributed media in print and online. Our sister newspaper, The Washington Blade, is the nation’s longest-running LGBTQ newspaper founded in 1969. It is also the only LGBT media member of the White House Press Corps.

As the new publisher of the Los Angeles Blade, I will work hard to honor the brand of The Blade and the work that Troy, our previous journalists and editors, and our community partners did to make us who we are today. A very heartfelt thank you to our readers and advertisers who continue to support our efforts.

Despite what is going on socially and politically towards the queer community, we will continue to thrive.

Alexander Rodriguez, Publisher

Please consider supporting the continuing efforts of the Los Angeles Blade with your financial contribution. For just dollars a month, your support makes vital LGBTQ journalism possible at a time when clear, concise news is needed more than ever.

For advertising opportunities, please contact Alexander Rodriguez at [email protected]

Today marks our 8th anniversary as SoCal’s LGBTQ+ news source and we want to thank you all for the support through the years. The Blade was founded in 2017 by Troy Masters, two years after he moved to Los Angeles in search of community and a fresh start for the next stage in his journalism journey.

He founded the Los Angeles Blade, because he saw the overwhelming need for accurate and unbiased news reporting for the LGBTQ+ community during a time where many other mainstream news outlets were overlooking the stories that affected our communities, such as the AIDS crisis.

In our everyday work since then, we aim to cover the issues that not only affect us, but that also inform us and spotlight our amazing talents, skills and ability to unite. We always aim to be a beacon of light, education and information for our communities because under this current administration, Trump has seemingly vowed to take us back into the dark ages and erase any and all progress we have painstakingly made throughout time.

My goal as editor is to include voices that make up our community and continue building trust with those voices, so that our work can serve you and everyone else under the LGBTQ+ and QTBIPOC umbrellas.

It’s true, Democracy dies in darkness and as members of the media, we must double-down in our efforts to provide accurate, informative and relevant news to our communities now more than ever.

The Blade has seen leadership shifts within the last six months, including myself, and we hope that these changes encourage you to support us and see how we continue growing.

Please reach out to us to discuss how we can better serve you or our communities. Don’t forget to subscribe to our weekly newsletter and donate to the Blade Foundation if possible.

Thank you all so much for your trust and support during these particularly difficult times.

Gisselle Palomera, Editor

Contact me at [email protected].

History

LGBTQ+ History Archive Gains Momentum: Personal Stories Project Partners with George Takei

Increased Awareness Through Social Media Reach

The LGBTQ+ History Archive Personal Stories Project is experiencing a surge in submissions. This decade-long effort documents LGBTQ+ history through personal narratives. Its success stems from a new partnership with actor George Takei and the .gay domain provider.

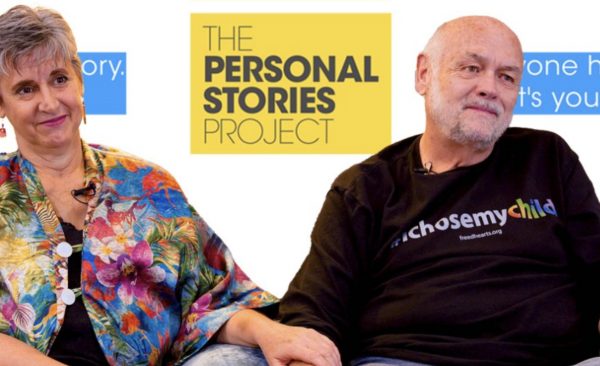

Charles Chan Massey co-founded and directs the Personal Stories Project. He credits the partnership’s success to Takei’s vast social media following. Takei, a vocal LGBTQ+ rights advocate, encouraged his 3.3 million X followers to share their stories.

Takei posted: “Each of us in the LGBTQIA+ community has a powerful coming-out story to tell. I want to hear yours. Head over to personalstories.gay today. Fill out the form to be featured on the Personal Stories website. I’ll be sharing some throughout the month to inspire others.”

Amplifying Community Voices

Logan Lynn is the creative director of .gay Domains. He emphasizes the partnership’s role in amplifying vital LGBTQ+ voices.

“Pride is about honoring and celebrating the depth of our communities,” Lynn said. “What better way to showcase this than through stories from people living LGBTQIA+ lives?”

Preserving Everyday Stories for Future Generations

Massey founded the LGBTQ+ archive project in 2012. His mission: preserve narratives of ordinary LGBTQ+ individuals, not just prominent figures.

“I wanted to archive our community’s history,” Massey explained. “Not just prominent members, but regular people who needed a platform. Regular people can identify with regular people. It’s important to see someone just like you.”

Massey maintains an online archive. This ensures accessibility of these oral histories for the LGBTQ+ community.

“As long as the internet exists, it can archive our stories,” Massey said. “We’re preserving stories for future generations. We’re also helping people find others with similar journeys.”

From Facebook Page to Registered Charity

The LGBTQ+ History Archive Personal Stories Project started as a simple Facebook page. It has evolved into a dedicated website and registered charity. It now supports LGBTQ+ organizations across the US and Canada.

Many participants share how LGBTQ+ organizations helped them. The Personal Stories Project encourages donations to these charities. Massey reports raising $15,000 to $25,000 annually for over 20 non-profits.

“95% of our budget goes to other 501(c)(3) organizations,” Massey said. “We support large and small community-based groups. A $200 donation can make a significant difference.”

A Diverse Collection of Experiences

The Personal Stories Project has a vast collection of LGBTQ+ stories. Massey is often struck by the depth of experiences shared.

“I met Peter, who was 85 at the time,” Massey shared. “He served in the Air Force, modeled in the 1940s, started an ad agency, and lived through the AIDS crisis. His story shows the power of these narratives.”

The project seeks submissions from all parts of the LGBTQ+ community. This includes people of various ethnicities and generations.

“People often think their story isn’t interesting,” Massey said. “But when they share, it’s captivating! Someone will identify with your story. Sharing is a powerful gift and a responsibility.”

Share Your Story

Do you have an LGBTQ+ story to share? Visit personalstories.gay to contribute to this important historical archive.

Image from Personalstories.gay website

History

The world-changing decision by psychiatrists that altered gay rights

December 15, 1973, was hailed by gay rights activist Frank Kameny as the day “we were cured en masse by the psychiatrists”

WASHINGTON – Fifty years ago this past Friday, on December 15, 1973, a decision by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) at its annual convention was hailed by gay rights activist Frank Kameny as the day “we were cured en masse by the psychiatrists.”

The board of trustees of the APA voted to remove homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is used by health care professionals in the United States and much of the world as the authoritative guide to the diagnosis of mental disorders.

Washington Post writer Donald Beaulieu noted in an article published on the 50th anniversary that newspaper stories the next day mostly treated it as a technical change rather than a seismic shift that would transform the lives of gay people. But for gay rights activists Barbara Gittings, Kameny, Paul Kunstler, Jack Nichols, Elijah ‘Lige’ Clarke, Lilli Vincenz, and Kay Tobin Lahusen, it was groundbreaking.

Kameny and Nichols in 1961 had formed The Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., that the others were actively engaged in with the purpose of conducting gay rights protests at the White House, the United States Civil Service Commission, and the Pentagon. By the late 1960’s the group also focused on efforts to declassify homosexuality as a mental illness.

Kameny and Gittings were determined to get the APA to act. Nichols, Clarke, Gittings and Lahusen would create some of the earliest gay themed content, stories and columns in early gay national publications.

Nichols with his partner Clarke, wrote the column “The Homosexual Citizen” for Screw magazine, a pornographic ‘straight’ tabloid publication in 1968. Lahusen’s photographs of lesbians appeared on the cover of The Ladder as Gittings worked as its editor. The Ladder, published by the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), was the first national lesbian magazine.

In the August 1964 issue of The Ladder, Gittings’ editorial blasted a medical report that described homosexuality as a disease, writing that it treated lesbians like her more as “curious specimens” than as humans.

In 1971, some seven years later at the annual meeting of the APA, Gittings, Kameny and fellow gay activists stormed the meeting and Kameny seized the microphone, demanding to be heard. The Washington Post reported:

Kameny, who had lost his job as an astronomer with the Army Map Service in 1957 because he was gay, grabbed the microphone from a lecturer at the convention and addressed the room. “Psychiatry is the enemy incarnate,” he told the shocked audience. “Psychiatry has waged a relentless war of extermination against us. You may take this as a declaration of war against you.”

For the APA’s annual meeting in 1972, Kameny and Gittings organized a panel on homosexuality. When no gay psychiatrist would serve on it openly for fear of losing his medical license and patients, Gittings recruited Dr. H. Anonymous (John E. Fryer, M.D.), who appeared masked and using a voice modulator.

Gittings, Kameny and Dr. Anonymous asserted that the disease was not homosexuality, but toxic homophobia. Consequently, the APA formed a committee to determine whether there was scientific evidence to support their conclusion.

The Post noted: “This is the greatest loss: Our honest humanity,” Fryer said. “Pull up your courage by your bootstraps and discover ways in which you and homosexual psychiatrists can be closely involved in movements which attempt to change the attitudes of heterosexuals — and homosexuals — toward homosexuality.” Fryer received a standing ovation. He would not reveal his identity until 1994, 22 years later.

“In 1973, with Gittings and Kameny present by invitation, the APA announced its removal of the classification. Kameny described it as the day “we were cured en masse by the psychiatrists.” At the time, the “cures” for homosexuality included electric shock therapy, institutionalization and lobotomy. With the APA’s retraction, the gay rights movement was no longer encumbered by the label and its consequences.”

A symposium to address the issue occurred at the APA convention in Honolulu in May 1973 the Post reported. Panel members would represent both sides of the argument. There were those who fought the reclassification including one speaker who advocated retaining the homosexuality diagnosis, Charles Socarides, who received mostly boos from the crowd. Socarides asserted during the discussion, “All of my gay patients are sick.” According to Lawrence Hartmann, a psychiatry professor at Harvard University who served as APA president in the early 1990s, another panelist replied, “All of my straight patients are sick.”

According the Post, the last to speak was Ronald Gold, media director for the Gay Activists Alliance and the only panelist who was not a psychiatrist. Gold, who as a child was subjected to aversion therapy by a psychoanalyst, told the packed ballroom, “Your profession of psychiatry — dedicated to making sick people well — is the cornerstone of oppression that makes people sick.” Gold’s speech got a standing ovation, just as Fryer’s had the year before.

The legacy of that December decision fifty years ago continued when in 1998, the APA announced that it opposed any psychiatric treatment, such as “reparative” or conversion therapy, which is based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or that a patient should change his/her homosexual orientation.

In 2005, the APA established The John Fryer Award, which honors an individual who has contributed to improving the mental health of sexual minorities. The award is named for Dr. John Fryer, a gay psychiatrist who played a crucial role in prompting APA to review the scientific data and to remove homosexuality from its diagnostic list of mental disorders in 1973.

Out gay psychiatrist Amir Ahuja, who serves as president of the Association of LGBTQ Psychiatrists, told the Blade at an event celebrating the 50th anniversary of the historic speech by then closeted Fryer, that the positive outcome from Fryer’s efforts has had a direct impact on his own career.

“I would say I think John Fryer opened the door for me to have a career and many of my colleagues who are LGBTQ+ psychiatrists in order to work in a field where we’re not stigmatized as having an illness,” Ahuja said. “Because we could have lost our job. That’s what happened to John Fryer multiple times,” according to Ahuja. “Before he gave that speech, he had lost two residencies at least. Because of his sexuality, people were discouraging him from continuing in the profession.”

“John Fryer’s courageous actions were a watershed moment for psychiatry, the APA, and the LGBTQ community,” said Saul Levin, M.D., M.P.A., CEO & Medical Director of the American Psychiatric Association. “Every day we work to honor the legacy of Dr. Fryer and the activists who fought alongside him to achieve freedom, equality and acceptance for LGBTQ people in America.”

Additional reporting by Lou Chibbaro Jr.

History

Don’t ask – don’t tell, a Veterans’ Day reflection

On Sunday, Nov. 12 at 10 p.m. ET on MSNBC, and streaming on Peacock, ‘Serving in Secret: Love, Country, and Don’t Ask Don’t Tell’ will air

LOS ANGELES – On December 18, 2010, the U. S. Senate overturned the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy by a 65-31 vote, which President Barack Obama signed a few days later.

As LGBTQ veterans mark Veterans’ Day 2023 today, the Los Angeles Blade takes a look back at a series of policies that marginalized and persecuted the LGBTQ community’s military service, and the activists who successfully pushed the government to repeal them.

Don’t Ask – Don’t Tell Repeal Act of 2010

During World War II, the U.S. Armed Forces established a policy that discharged homosexuals regardless of their behavior. In 1981, the Defense Department prohibited gay and lesbian military members from serving in its ranks with a policy that stated, “Homosexuality is incompatible with military service.” In the decade following, 17,000 service members were discharged from their duties for being homosexual.

This spurred a new policy called “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” during the Clinton Administration. In November 1993, the Defense Authorization Act put “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” into effect, allowing gay and lesbian citizens to serve in the military as long as they did not make their sexual orientation public. Commanders were prohibited from inquiring about a service member’s orientation provided that they adhered to this condition. Additionally, the policy forbid military personal from discriminating against or harassing closeted homosexual service members and applicants.

By 2008, more than 12,000 officers had been discharged from the military for publicizing their homosexuality. On December 18, 2010, the Senate overturned the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy by a 65-31 vote, which President Barack Obama signed a few days later. The repeal allows gay and lesbian military members to serve openly in the armed forces.

Left: (using walker) Dr. John Cook from Richmond VA and his assistant; SLDN Board Chair Tom Carpenter; Mattachine Society of Washington DC founder Frank Kameny; retired Marine Sgt. Tom Swann; unidentified tall guy: Pat Kutteles, mother of murdered infantry soldier Barry Winchell; politico David Mixner; and SLDN attorney Aaron Tax.

(Photo courtesy Tom Carpenter)

On the anniversary of the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal in 2018, former SLDN Board Chair Tom Carpenter wrote a reflection for the Los Angeles Blade:

“Many in our community never understood why any LGBT citizen would ever want to become part of a military that proclaimed “Homosexuality is incompatible with military service,” often sending LGBT service members to prison because of who they loved. The hard-core anti-war/military crowd wanted no part in the fight to lift the ban on open service. Bowing to these objections, many large LGBT organizations paid nothing more than lip service to this effort.

As a candidate, Bill Clinton promised to lift the ban. Clinton had no idea the forces that opposed this change in policy. Those of us, who had served, knew better. The military and Senate leadership blocked him, including members of his own party. Instead of a policy, in 1993, we ended up with a federal law—“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” (DADT). This law proved almost as bad for LGBT service members as the outright ban.

Shortly after the law went into effect, two young lawyers, former Army Captain Michelle Beneke and Dixon Osburn, established Servicemembers Legal Defense Network (SLDN). They realized other LGBT organizations had neither the desire, nor expertise, to take on the task of providing legal assistance to those who would likely run afoul of the law. Their ultimate goal was to repeal the law in its entirety, allowing for open and honest service.

I joined the board of SLDN in 1994 and served as its co-chair for 7 years. It was clear to us that it would be another 10-20 years before Congress would be willing to take up this hot-button issue again. During the administrations of George W. Bush from 2000-2008, we felt as if we were in the wilderness. Thousands of service members were being discharged as the military asked, and some LGBT service members told. SLDN provided legal assistance to many and saved numerous careers.

Our arguments of how unfair the law was, and how much it was costing taxpayers to train replacements for highly skilled service members who were discharged, gained little traction. Sadly, it was the brutal murders of a sailor, Allan Schindler, and a soldier, Barry Winchell that finally focused attention on why this law was counterproductive to military readiness, unit morale and discipline. Both these young men were brutally beaten to death because one of their fellow service members merely thought they were gay.

These two tragedies captured the attention of the country. At SLDN, we recognized it was personal stories that would humanize this fight for equality. The mother of Schindler, as well as the parents of Winchell actively participated in SLDN’s lobbying efforts on Capitol Hill. Their emotional appeal to members of Congress was powerful. But it was not enough.

Our strategy was to have veterans in the forefront of the lobbying and media effort. Especially effective were those who had been discharged, resigned their commissions, or did not reenlist because of their sexual orientation. The most compelling personal stories came from Arabic linguists, medics, pilots, and infantrymen who had been on the front lines in the Global War Against Terror. Many of these veterans appeared on television and had their stories reported by the press. Through these efforts, it was becoming ever more clear to the public, the law was not working. These veterans made the case by revealing the simple truth—the law was contrary to the core values of the services. It required them to live a lie.

It was not until Barack Obama was elected in 2008 that we started to see an end game. With a Democrat in the White House and a more friendly Congress, we continued our strategy of telling personal stories. By this time over 12,000 patriots had lost their careers. There was much foot dragging from the White House during the early part of President Obama’s first term. The memory of what had happened to President Clinton’s effort, sixteen years earlier, clearly impacted the willingness to spend political capitol on this issue.

By 2010, SLDN marshaled Congressional allies and helped draft a bill to repeal DADT. It was becoming clear SLDN”s media and lobbying efforts had changed public opinion. Most Americans now favored repeal of DADT. Further, the Pentagon was being threatened by a series of lawsuits that challenged the law. The turning point was when the Senate held hearings and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates testified he favored repeal. In contrast to 1993, the Joint Chiefs of Staff agreed.

In the lame duck session of the 111th Congress, notorious for inaction, a true miracle occurred. In a stroke of legislative brilliance, led by Army veteran, Congressman Patrick Murphy, DADT was repealed. On Dec. 22, 2010, President Obama signed the repeal law.

With the repeal of DADT, the first leg of institutional bias had collapsed. As predicted, in 2015, after a tremendous effort by LGBT groups, the Supreme Court ruled all Americans, regardless of sexual orientation, had a fundamental right to marry.

The only institution remaining in the way of equality is ministry. “Religious liberty” is now the rallying cry of the opponents of freedom for all Americans. While progress is being made, many battles still lie ahead. Never give up!”

(Photo by Karen Ocamb)

On Sunday, Nov. 12 at 10 p.m. ET on MSNBC, and streaming on Peacock, ‘Serving in Secret: Love, Country, and Don’t Ask Don’t Tell’ will air:

In 1970, Tom Carpenter graduated from the Naval Academy ready to follow his family’s lineage in the military as a US Marine Corps attack pilot. Then he met Courtland Hirschi. Tom and Court fell deeply in love, keeping their illicit relationship a secret. At that time, homosexuality – if discovered – resulted in being kicked out of the military with a dishonorable discharge, a court martial, jail time, or worse… Tom and Court’s story would be no exception. ‘Serving in Secret’ features leading voices in politics, historians, civil rights activists, and retired military personnel telling the story of LGBTQ discrimination in the military, and the controversial compromise known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Tom’s work towards its repeal along with many others was the Turning Point for LGBTQ+ rights, a fight that continues today.

‘Serving in Secret: Love, Country, and Don’t Ask Don’t Tell’ (Link)

History

Hate: The bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church remembered

Sixty years after four little girls were killed in the bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church, at 10:22 a.m., the church rang its bells

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — It was a quiet Sunday morning in Birmingham—around 10:24 on September 15, 1963—when a bomb made from dynamite exploded in the back stairwell of the downtown Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Minutes before a white man was seen placing a box under the steps of the church.

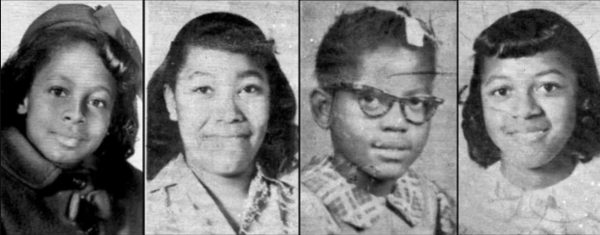

The blast killed Addie Mae Collins, 14; Carole Robertson, 14; Cynthia Wesley, 14; and Denise McNair, 11 injuring 20 more and left the sister of Addie Mae Collins, 12-year-old Sarah Collins Rudolph, suffering from not only the loss of her sister, but her eyesight as well.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation notes in the agency’s history of the event that the bombing was a clear act of racial hatred: the church was a key civil rights meeting place and had been a frequent target of bomb threats.

(Photo Credit: Photographic collections of the Library of Congress)

Addressing the American people on Monday, September 16, 1963, President John F. Kennedy said:

“I know I speak on behalf of all Americans in expressing a deep sense of outrage and grief over the killing of the children yesterday in Birmingham, Alabama. It is regrettable that public disparagement of law and order has encouraged violence which has fallen on the innocent. If these cruel and tragic events can only awaken that city and State–if they can only awaken this entire Nation–to a realization of the folly of racial injustice and hatred and violence, then it is not too late for all concerned to unite in steps toward peaceful progress before more lives are lost.

The Negro leaders of Birmingham who are counseling restraint instead of violence are bravely serving their ideals in their most difficult task–for the principles of peaceful self-control are least appealing when most needed.

Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall has returned to Birmingham to be of assistance to community leaders and law enforcement officials–and bomb specialists of the Federal Bureau of Investigation are there to lend every assistance in the detection of those responsible for yesterday’s crime. This Nation is committed to a course of domestic justice and tranquility–and I call upon every citizen, white and Negro, North and South, to put passions and prejudices aside and to join in this effort.”

The FBI’s account of the aftermath and investigation

At 10:00 p.m. that night, Assistant Director Al Rosen assured Assistant Attorney General Katzenbach that “the Bureau considered this a most heinous offense…[and]…we had entered the investigation with no holds barred.”

And we backed that promise up. Dozens of FBI agents worked the case throughout September and October and into the new year—as many as 36 at one point. One internal memo noted that:

“…we have practically torn Birmingham apart and have interviewed thousands of persons. We have seriously disrupted Klan activities by our pressure and interviews so that these organizations have lost members and support. …We have made extensive use of the polygraph, surveillances, microphone surveillances and technical surveillances…”

By 1965, we had serious suspects—namely, Robert E. Chambliss, Bobby Frank Cherry, Herman Frank Cash, and Thomas E. Blanton, Jr., all KKK members—but witnesses were reluctant to talk and physical evidence was lacking. Also, at that time, information from our surveillances was not admissible in court. As a result, no federal charges were filed in the ‘60s.

It has been claimed that Director Hoover held back evidence from prosecutors in the ‘60s or even tried to block prosecution. But it’s simply not true. His concern was to prevent leaks, not to stifle justice. In one memo concerning a Justice Department prosecutor seeking information, he wrote, “Haven’t these reports already been furnished to the Dept.?” In 1966, Hoover overruled his staff and made transcripts of wiretaps available to Justice. And he couldn’t have blocked the prosecution and didn’t—he simply didn’t think the evidence was there to convict.

For its part, the FBI noted that in the end, justice was served.

Chambliss received life in prison in 1977 following a case led by Alabama Attorney General Robert Baxley. And eventually the fear, prejudice, and reticence that kept witnesses from coming forward began to subside. We re-opened our case in the mid-1990s, and Blanton and Cherry were indicted in May 2000. Both were convicted at trial and sentenced to life in prison. The fourth man, Herman Frank Cash, had died in 1994.

Marking the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, 60 years later

Birmingham NBC News affiliate WVTM-TV 13 reported that the 16th Street Baptist Church rang its bells in honor of bombing victims 60 years later at 10:22 a.m. and read the victims’ names out loud in remembrance.

U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was the keynote speaker Friday during the commemoration service at 16th Street Baptist Church 60 years after the bombing that killed four girls.

In her remarks, Jackson, the first Black woman to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court, standing at the pulpit in the historic church told those gathered for the commemoration services,

“Today we remember the toll that was paid to secure the blessings of liberty for African Americans and we grieve those four children who were senselessly taken from this earth and their families robbed of their potential,” Jackson said.

”The work of our time is maintaining that hard-won freedom and to that we are going to need the truth, the whole truth about our past,” the Justice said noting that while the American nation should celebrate the advancements that have been made since 1963, there is still work to do.

Jackson said she knows that atrocities “like the one we are memorializing today are difficult to remember and relive” but said it is also “dangerous to forget them.”

“If we are going to continue to move forward as a nation, we cannot allow concerns about discomfort to displace knowledge, truth or history. It is certainly the case that parts of this country’s story can be hard to think about,” she said adding, “Yes, our past is filled with too much violence, too much hatred, too much prejudice, but can we really say that we are not confronting those same evils now? We have to own even the darkest parts of our past, understand them and vow never to repeat them.”

Related:

Birmingham church bombing survivor speaks out 60 years later:

History

‘Fagots Stay Out:’ Protest at Barney’s Beanery 53 years ago today

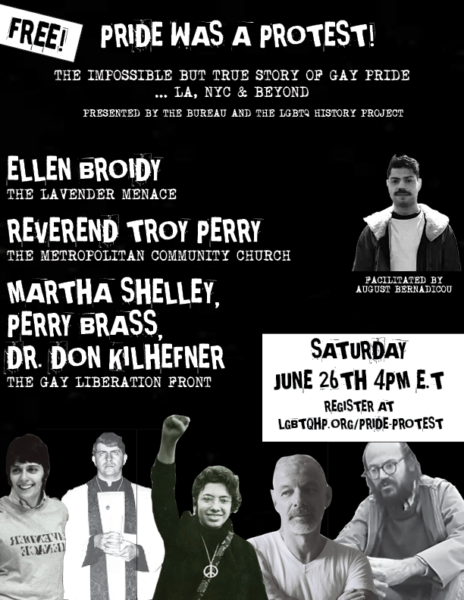

Rocco interviews Morris Kight, founder of the California chapter of the Gay Liberation Front and a young Rev. Troy Perry

By Paulo Murillo | WEST HOLLYWOOD – The Academy Awards Museum recently featured three short films by trailblazing Los Angeles-based filmmaker and gay rights advocate Pat Rocco (1934–2018) last week, courtesy of Outfest UCLA Legacy Project at the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Films featured were “Sign of Protest” (1970), “Meat Market Arrest” (1970), and “We Were There” (1976).

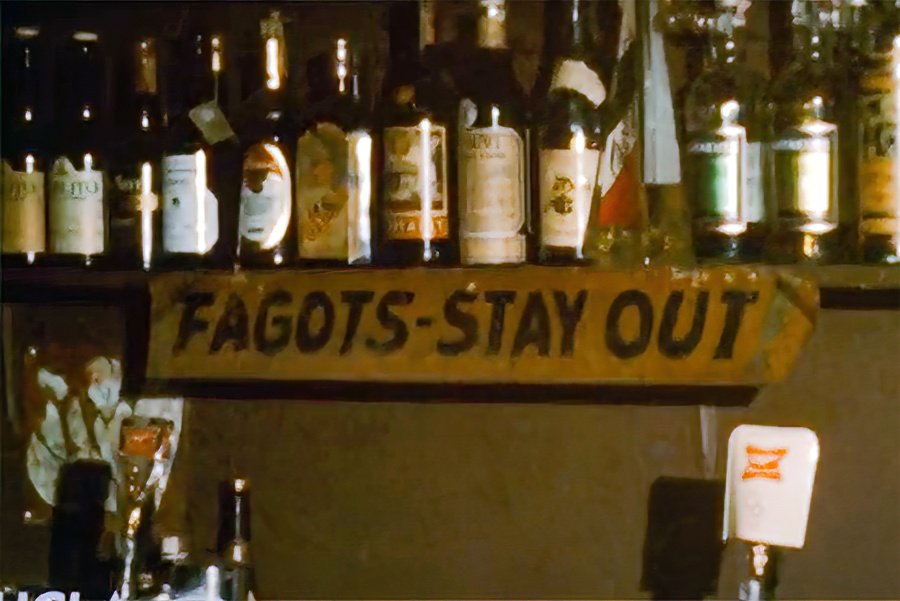

The short film “Sign of Protest” documents a February 7, 1970, gay liberation march outside Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood, protesting a famous sign that read “Fagots [sic]–stay out” which hung proudly over the bar.

Rocco plays the role of neutral reporter on the scene in this activist interpretation of a newsfilm, interviewing the bar’s owners and patrons, as well as the protestors, and allowing their comments to speak for themselves.

Rocco is shown speaking with the daughter of the bar’s owner, who states nonchalantly that the sign has been up since 1959 and was originally accompanied by many more (since removed). She further states that the sign is part of the restaurant’s history and will not come down unless Barney’s is legally mandated to remove it.

Rocco then goes over to the sign posted above the bar and interviews customers about their opinion of it, which is largely positive.

Next, Rocco joins the 50 protesters outside and interviews Morris Kight, founder of the California chapter of the Gay Liberation Front, the organization that spearheaded the picket and a young Rev. Troy Perry, founder of the gay-affirming Metropolitan Community Church, who reiterates many of the comments heard from other protesters that the sign is offensive and should be taken down as a civil rights violation.

He also mentions a June 26, 1964, LIFE Magazine article about Barney’s Beanery and the controversial sign where the owner says homosexuals should be shot.

For those who missed on the big screen or wish to revisit it, the short film is available on YouTube, however, view at your discretion due to language some may find offensive.

Trailblazing Los Angeles-based filmmaker and gay rights advocate Pat Rocco (1934–2018) began his moviemaking efforts as a creator of queer male erotica in the late 1960s. When the public’s appetite shifted to hardcore, Rocco pivoted to documenting moments of LGBTQ protest and collective joy in his adopted city, often appearing on camera as an always gracious (and meticulously coiffed) interviewer of his many subjects.

Whether out in the streets capturing a demonstration of Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood against their defamatory anti-gay signage (Signs of Protest), on the scene of an escalating situation with law enforcement at a gay bar (Meat Market Arrest), or capturing LA’s energetic early Pride parades (We Were There), Rocco’s films always culminate in moments of hope and a spirit of liberation that feel akin to Varda’s own joyful yet always inquisitive Weltanschauung.

**************************************************************************************

Paulo Murillo is Editor in Chief and Publisher of WEHO TIMES. He brings over 20 years of experience as a columnist, reporter, and photo journalist.

******************************

The preceding article was previously published by WeHo Times and is republished with permission.

History

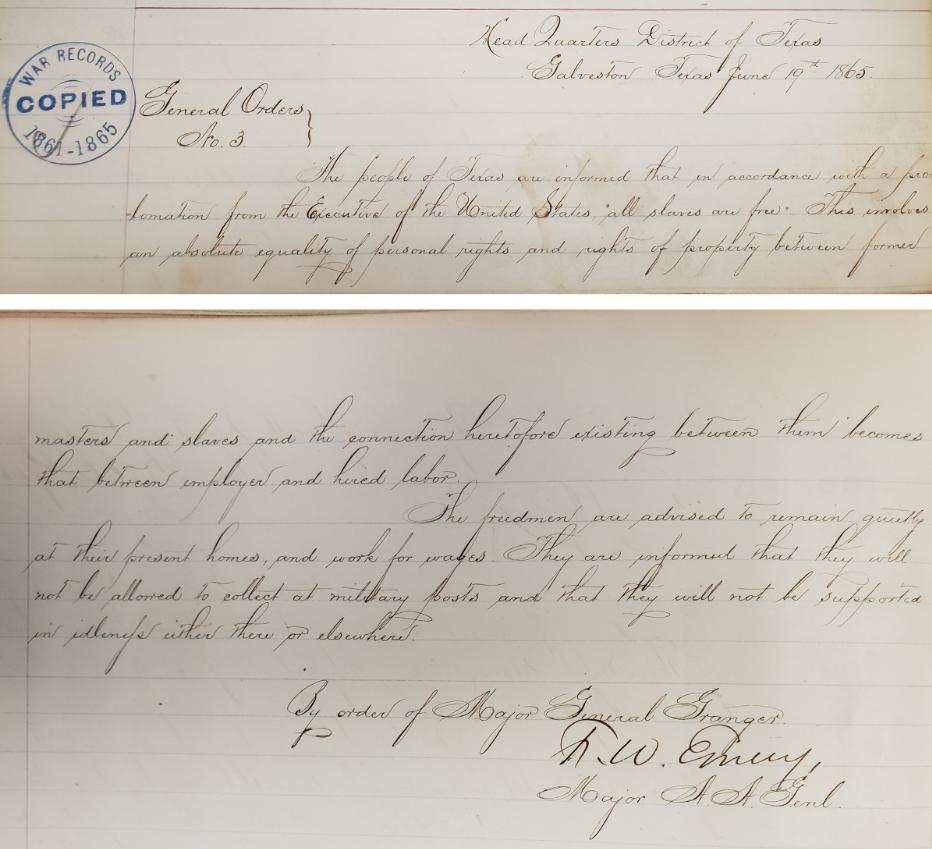

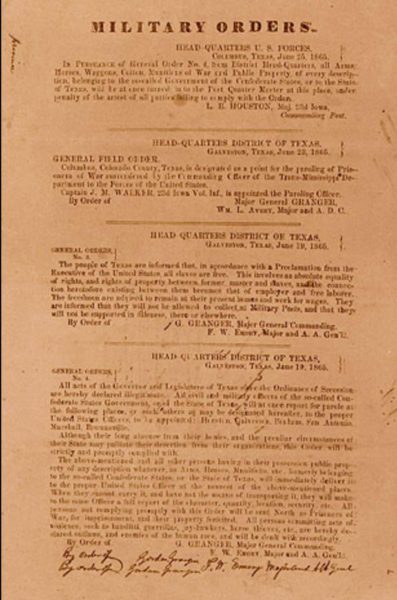

Marking slavery’s end, a historic event now marks a Federal holiday

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free”

GALVESTON, Tx. – In the early summer of 1865, on a clear crisp June morning, the lead elements of the Federal Army of blue-coated soldiers of the 13th Army Corps occupied the island city of Galveston, Texas on Monday the 19th.

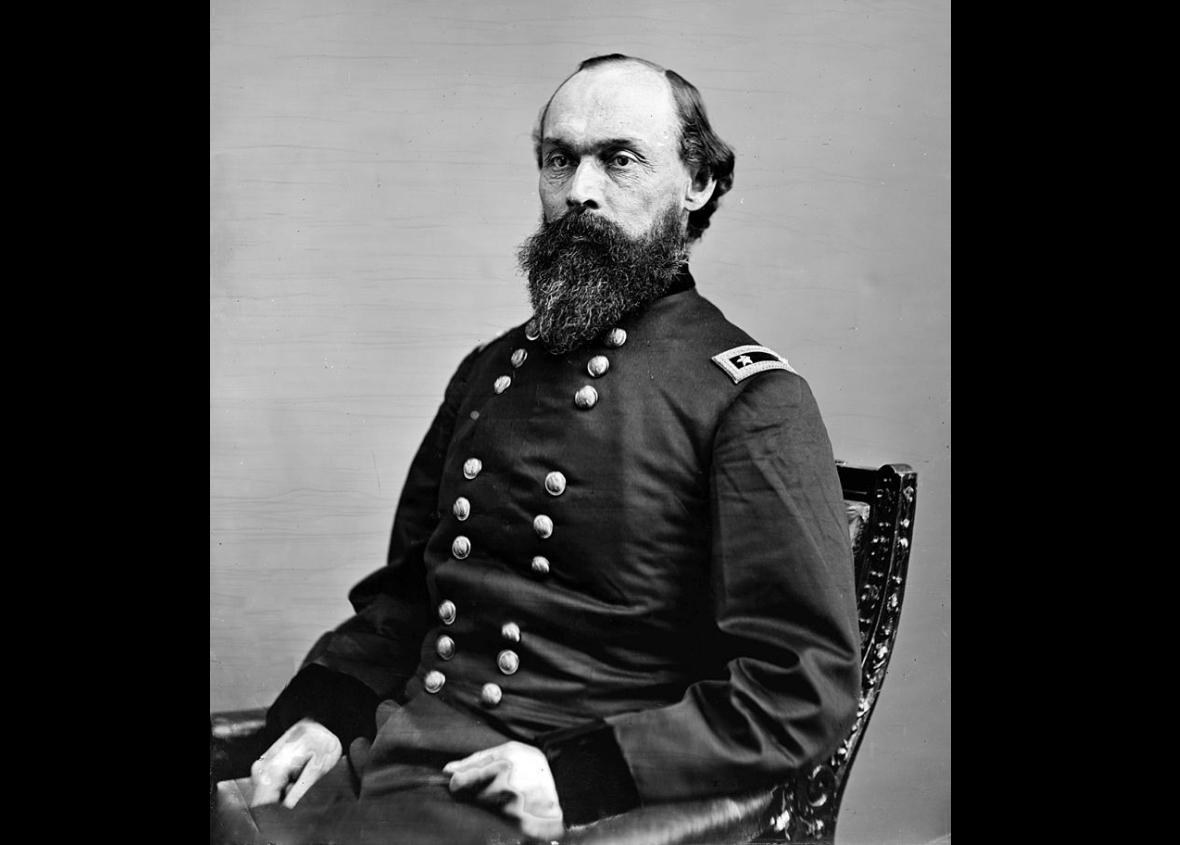

Led by Union Army Major General Gordon Granger, who had recently taken command of the Department of Texas, the 13th Corps was tasked with enforcement of the emancipation of slaves in the former Confederate state.

The bloody civil war had ended officially with the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia commanded by Robert E. Lee to Commander of Union forces, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia on April 9, 1865.

The warfare between the last elements of the Confederate and Union troops however, dragged on for another month or so culminating in the Battle of Palmito Ranch, which was fought on May 12 and 13, 1865. The fighting occurred on the banks of the Rio Grande east of Brownsville, Texas on the Texas-Mexico border some 400 miles Southwest of Galveston.

It took approximately another two weeks for Confederate Lieutenant General Simon B. Buckner to surrender his command of the Trans-Mississippi Department (which included Texas) to Union Major General Peter J. Osterhaus on May 26, 1865.

General Granger was then tasked with implementing the order to free enslaved African Americans.

Once Granger’s Federals had taken control of the port city, he and his command staff headed to Union Army Headquarters located at the Osterman Building, once located Strand Street and 22nd Street.

It was there that General Order No. 3 was first publicly read out loud to a gathering of now newly freed Black Americans and other citizens of the city.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Sadly it would take nearly two years before all of the enslaved African Americans would actually be freed in Texas by white plantation owners and others who simply didn’t tell them or defied Federal authorities.

In 2014, the Texas Historical Commission placed a subject marker at the corner of 22nd and Strand, near the location of the Osterman Building, where General Granger and his men first read General Orders, No. 3.

While many Black Americans across the former Confederate States would celebrate their freedom granted by The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln on Sep. 22, 1862 during the height of the war, in annual celebrations still others yet would annually mark the date of passage of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution by Congress on January 31, 1865, which abolished slavery in the United States.

Yet on Galveston Island, the tradition of marking their first learning of The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Lincoln with General Granger’s General Orders, No. 3, was the benchmark for ongoing annual celebrations and as the years went by as the Black Americans from the Lone Star state migrated ever Northward, it would be that seminal moment that ultimately would lead to the creation of a federal holiday and recognition some 156 years later.

One observer also wryly pointed out that the June anniversary was seasonally tied to better weather than the other two dates and more conducive to celebrations and large gatherings, hence its popularity in being established as the federal holiday.

Information and photographs provided by the National Archives, the City Of Galveston, Galveston Historical Foundation, the Library of Congress, and State of Texas, Texas Historical Commission.

History

50 years ago Atlanta’s nascent gay rights movement marched

“It was mostly about feeling good,” said Phil Lambert. “That we’re not a bunch of sick people. That we’re not the problem.”

ATLANTA, Ga. – This Sunday, exactly fifty years ago to the day on a bright Sunday morning, about a hundred brave gay and lesbian Atlantans from the Georgia Gay Liberation Front, unfurled a lavender colored banner made from a bedsheet with the intertwined symbols representing male + male, female + female with the a raised fist of defiance and the words ‘Gay Power’ emblazoned on it and they marched.

The group inched its way up Peachtree Street to a soundtrack of chants, kazoos and a tambourine.

Mindful that stepping off the sidewalks could get them arrested — the city of Atlanta had turned down their request for a permit and the police were closely watching for jay-walkers — the marchers stopped at every corner until they were given the crossing signal, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the average estimated crowds in attendance at Atlanta Pride is upwards of 300,000 plus. But at the time the Journal-Constitution noted, even in the city that had just birthed the civil rights movement and was home to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., LGBTQ rights was considered a radical issue that the Georgian liberal political establishment, including many Atlanta progressives, wanted to stay away from. At that time, gay sex was still illegal under state law, and the American Psychiatric Association characterized homosexuality as a mental illness.

For those GAGLF Atlantans who participated in that first pride march on June 27, 1971, the event was a turning point, a moment when, for the first time, they could publicly celebrate a part of themselves that society had long demanded they keep hidden.

“It was mostly about feeling good,” said Phil Lambert, a Vietnam veteran who was in attendance. “That we’re not a bunch of sick people. That we’re not the problem.”

Read the entire fascinating story: 50 years ago, Atlanta’s gay rights push took to street for first time

History

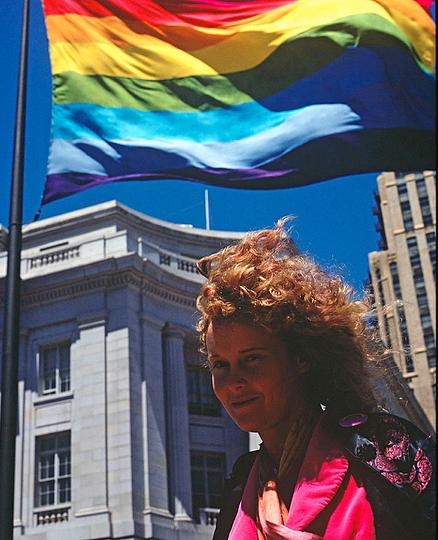

LGBTQ rainbow flag was born in San Francisco, but its history is disputed

On that day in June 1978, it felt as if the rainbow had always been a symbol for the LGBTQ community, it just hadn’t revealed itself yet

By August Bernadicou (with additional text and research by Chris Coats) | NEW YORK – Many enduring symbols that establish an instant understanding and define a diverse community are intrinsically linked with controversy, confusion, and ill-informed backstories dictated by vested interests and those who told the story loudest. The LGBTQ rainbow flag is no different.

While it was the work of many, the people who deserve credit the most have been minimized if not erased. Gilbert Baker, the self-titled “Creator,” screamed the story and now has a powerful estate behind his legacy. Before his death in 2017, Baker established himself as the complete authority on the LGBTQ rainbow flag. It was his story which he lived and became.

While there are disputed accounts on the flag’s origins, one thing that is not disputed is that the LGBTQ rainbow flag was born in San Francisco and made for the Gay Freedom Day Parade on June 25, 1978.

For all of human history, rainbows have mystified and inspired. A greeting of light and serenity after the darkness and chaos of a storm. They have symbolized hope, peace, and the mysteries of existence. For a moment, we can see the invisible structure, the “body” of light, made visible. A secret revealed, then hidden again.

Though it may seem like a modern phenomenon, rainbow flags have waved throughout history. Their origin can be traced to at least the 15th Century. The German theologian, Thomas Müntzer, used a rainbow flag for his reformist preachings. In the 18th Century, the English-American revolutionary and author, Thomas Paine, advocated adopting the rainbow flag as a universal symbol for identifying neutral ships at sea.

Rainbow flags were flown by Buddhists in Sri Lanka in the late 19th Century as a unifying emblem of their faith. They also represent the Peruvian city of Cusco, are flown by Indians on January 31st to commemorate the passing of the spiritual leader Meher Baba, and since 1961, have represented members of international peace movements.

Now, the rainbow flag has become the symbol for the LGBTQ community, a community of different colors, backgrounds, and orientations united together, bringing light and joy to the world. A forever symbol of where they started, where they have come, and where they need to go. When many LGBTQ people see a rainbow flag flowing in the wind, they know they are safe and free.

While the upper class and tech interests rule the city now, in the 1960s and 70s, San Francisco was a wonderland for low and no-income artists. The counterculture’s mecca. By the mid-1970s, the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood that had once been a psychedelic playground of hippie art, culture, and music had fallen into disarray. Hard, dangerous drugs like heroin had replaced mind-expanding psychedelics. Young queers and artists needed a new home, and they found it in the Castro.

Lee Mentley (1948-2020) arrived in San Francisco in 1972 and quickly fell in with the oddball artist and performers in the Castro neighborhood, donning flamboyant, gender-fucked clothes, performing avant-garde theater, and creating their own clubhouses. He was on the Pride Planning Committee in 1978 and ran the Top Floor Gallery on the top floor of 330 Grove, which served as an early Gay Center in San Francisco.

Lynn Segerblom (Faerie Argyle Rainbow) was originally from the North Shore of Hawaii and moved to San Francisco where she attended art school at the Academy of Art. Her life changed when she found a new passion in tie-dye and rainbows in the early 1970s. Entrenched in the free-loving technicolor world of San Francisco, in 1976, Lynn legally changed her name to Faerie Argyle Rainbow. She joined the Angels of Light, a “free” performance art troupe where the members had to return to an alternative, hippie lifestyle and deny credit for their work.

Shortly after the original rainbow flags were flown for the last time, both Lynn and Lee moved out of San Francisco. Lee moved to Hawaii and Lynn moved to Japan. When they returned, they were shocked to see how their contribution to history was becoming a universal symbol. They remain passionate about defending their legacies and giving a voice to the mute.

——–

LEE MENTLEY: “One day in 1978, Lynn came to 330 Grove with a couple of her friends, James McNamara and Robert Guttman, and said we should make rainbow flags for Gay Day to brighten up San Francisco City Hall and Civic Center because it’s all gray and cold in June. We thought that it sounded like a great idea.”

To get over the first hurdle, money, the young artists went to Harvey Milk, the first openly gay elected official in the history of San Francisco, California, for help.

LEE: “There was no actual funding for it. We contacted Harvey Milk and another supervisor, and they asked the city if we could get a little funding. They found some leftover funds from the previous year’s hotel tax, and we got $1,000.”

LYNN SEGERBLOM: “I remember having a meeting where I presented the idea of making rainbow flags. I had some sketches. At that meeting, there was just a handful of us there, and I remember, and even my friend assured me, that Gilbert Baker was not at that meeting. I don’t know where he was, I didn’t keep track of him, but he was not at the meeting where I suggested rainbow flags. We decided, yes, rainbow flags sounded great.”

The committee approved the rainbow imagery and made the decision to make two massive 40’ x 60’ foot rainbow flags to be flown at the Civic Center along with 18 smaller rainbow flags designed by different, local artists, to line the reflecting pool putting rainbows into the grey sky.

For the two large flags, one would be an eight-color rainbow starting with pink and including turquoise and indigo in place of blue, and the other a re-envisioning of the American flag with rainbow stripes which became known as Faerie’s flag.

——

Gilbert Baker’s name on his memoir, Rainbow Warrior, it says “CREATOR OF THE RAINBOW FLAG,” leaving little debate that Gilbert claimed full ownership for the concept and design of the legendary symbol. He never denied Lynn or James MacNamara’s involvement in the flags’ construction and speaks briefly and fondly of them and their talents in that same book.

LEE: “We didn’t need one person saving our ass, and it certainly wouldn’t have been Gilbert Baker. He was no Betsy Ross. He was a very good promoter, and I give him all the credit in the world for making the rainbow flag go international. He did a great service, and he was a very talented, creative man, but he could never have done all of the work by himself; no one could have.

We never considered ownership. There was never this big ownership debate until Gilbert started it. Because AIDS hit us so fast after this, most of our leadership either went into HIV activism or died.”

LYNN: “The story is that a white gay man did all of this by himself, but, in fact, that is not true at all. He just promoted it. For that, though, he should be given great love.”

————

Making the two original rainbow flags was no easy feat. With a limited budget and limited resources, the group had to improvise and figure it out as they went along. While Lynn had dabbled in flags before, a project of this scope and importance was far beyond her comfort zone.

LEE: “The community donated the sewing machines we used. We asked people at the Center if anyone would like to volunteer. All sorts of people from all over the country helped us with the flags, over 100 people, which, to me, is an amazing story. That’s where it came from. It came from regular artists who wanted to have fun and make something pretty for gay people.”

LYNN: “The Rainbows Flags were hand-dyed cotton and eight colors. I made two different types. The one with just the stripes and then the American flag one, which I designed myself. There was a group of us that made them, James McNamara, Gilbert Baker, and myself. Originally they were my designs. I was a dyer by trade, and I had a dying studio at the Gay Community Center at 330 Grove Street.”

LEE: “People would come and help as long as they could. Then, somebody else would come and help as long as they could. We opened up the second floor of 330 Grove to people who came to be in the Parade and march. People came in and made posters, banners and did art stuff.”

LYNN: “We made the flags on the roof because there was a drain up there. There was a wooden ladder that led up to the roof. The hot water had to be carried up to the roof because we didn’t have hot water up there. We heated it up on the stove in pots. We put the hot water in trash cans on the roof.”

LEE: “We had trash cans and two by fours, and we had to keep agitating the fabrics in the dye. Since they were in hot water, they had to be poked and agitated for hours.”

LYNN: “We had to constantly move the fabric in the dye, so the dye penetrated the fibers that weren’t clamped tight. We had to make sure there would be blue, and it wouldn’t just be white on white or white with a very murky, pale blue.

After they were washed and dyed, they went through the washer and dryer. Then, we ironed them. If the fabric stays out too long, once you take it out of the water, if it sits on itself even for just a few minutes, it starts to make shapes.”

—-

LEE: “Lynn’s flag, the new American flag, was a similar rainbow, but it had stars in the corner. I have photographs of that flag flying at gay events in San Francisco at City Hall and Oakland.”

LYNN: “I always liked the American flag. I thought, oh, wouldn’t that be nice? I knew with some luck I could make it.”

LEE: “I thought the one with the stars was more interesting because it symbolized a new flag for the United States.”

LYNN: “For my American flag, I decided to flip the order of the colors, so pink was at the bottom and purple was at the top in an eight-color spectrum. That was intentional. I wanted them to be different.